Cosy games are weird in that they’re not so much a genre as a vibe. As my colleague Eric Switzer wrote earlier this year, the cosy game is more about the feeling a game evokes than what the game actually is.

Browsing the ‘cosy’ tag on Steam reveals games that lie in a variety of genres. There are games like Tiny Glade, focusing on building and creative expression. There are games like Stardew Valley, centering on simulating farming or life. There’s Little Kitty Big City, where you play a cat exploring the city. There are also puzzlers like A Little to the Left.

What do they all have in common? Really, not all that much. They don’t center on combat or violence. They generally don’t involve time pressure or competition. They’re all indies, though Stardew Valley is a household name, and similar big budget games like Animal Crossing also get the same descriptor. Cosy is an umbrella term, one that encompasses basically everything that might make players feel calm and at ease. Yet cosiness is a highly personal thing – what’s cosy to me (blasting dirt off walls in PowerWash Simulator while listening to horror podcasts) might seem unbearably dull or unpleasant to someone else.

Related

ZA/UM’s Project C4 Is Fighting A Battle It Can’t Win

ZA/UM has lost so much goodwill that it’s not even close to being the most popular Disco Elysium successor.

A Cosy Game About Not Being Cosy

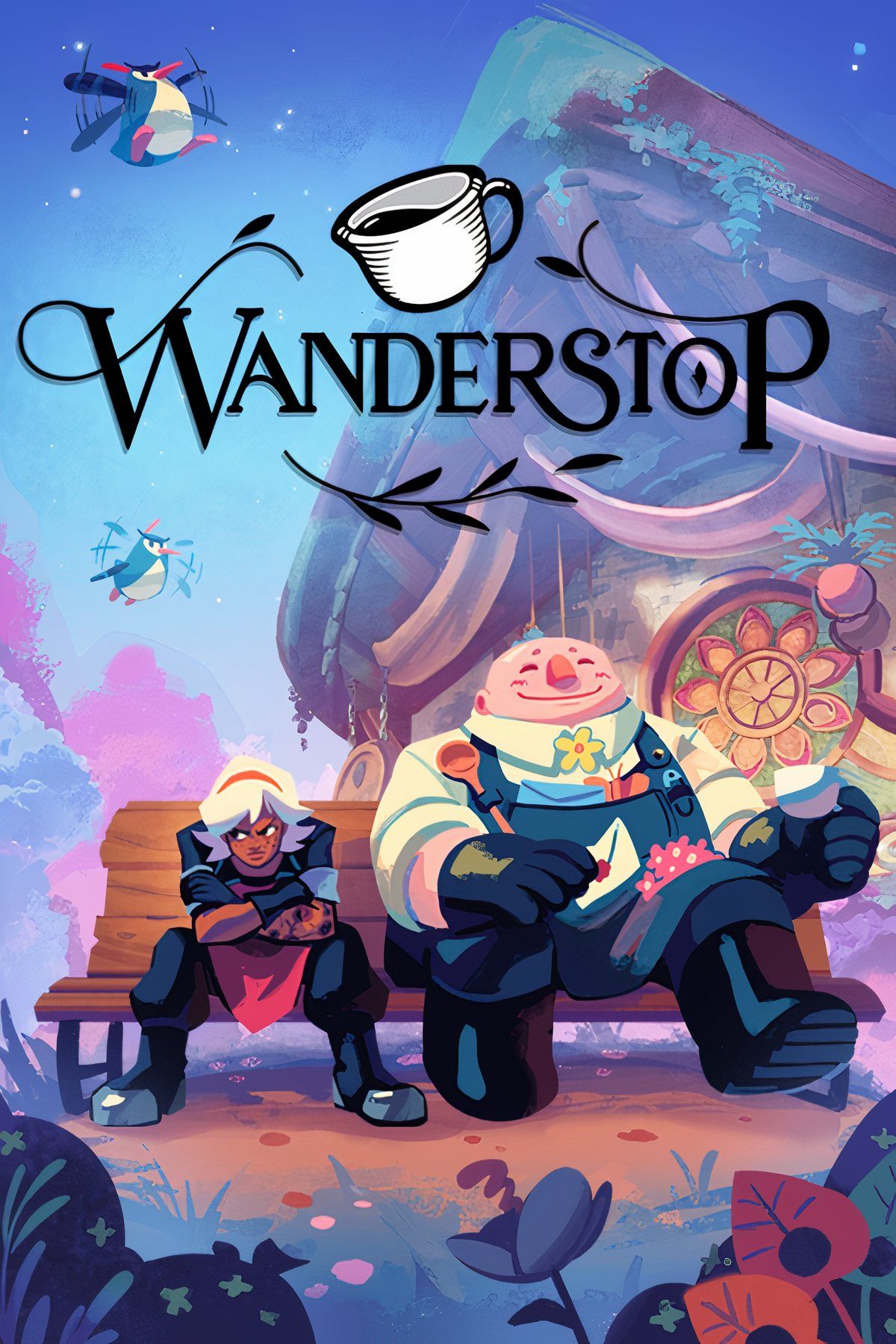

Wanderstop is, for all intents and purposes, a cosy game. It has all the hallmarks of a cosy game: it’s about tending plants, making tea, and serving customers, with no time pressure. It has no combat, or any violence at all, at least within the game itself. It’s story-forward, funny, and heartwarming, with a strong cast of largely endearing characters. It has cute animals that you can pick up and pet.

These are all very Cosy Game Things. But Wanderstop is interesting because these mechanics run counter to the protagonist’s inner turmoil. Alta is suffering from burnout, induced by her own insatiable drive to work and succeed at all costs. When she eventually arrives at Wanderstop, carried to the tea shop after passing out in the woods from exhaustion, she agrees to help Boro run the tea shop in an attempt to ‘cure’ her burnout.

A more typical protagonist might embrace this lifestyle. Alta, though, finds herself incensed by everything. She struggles to accept that people might come to the shop with no intention to drink tea. She’s antsy because there isn’t enough to occupy her hands with. She’s frustrated that everything takes time. Her struggle is to learn to enjoy the cosy game loop, the routine, the slow pace, the little details. She doesn’t want to be cosy, but she has to learn to do it, for her own sake.

Why Do We Need Cosy Games?

Wanderstop is fairly unique in how it’s taken the cosy game template and subverted its tropes. There are other games playing with genre (I say this very loosely) expectations – Blumhouse Games’ upcoming Grave Seasons is a horror farming and town sim about supernatural murders – but I’d say the majority of cosy games are cosy for cosy’s sake. They want to elicit a reaction or feeling from players, allowing them to get lost in the world. This is, in itself, not a problem, but isn’t particularly interesting either.

What is interesting is when cosy games challenge the player’s understanding of cosiness, asking them what it is they’re craving, and why they’re craving it. Cosy games can be an easy, accessible way to escape the seemingly never ending horrors of the real world. In Stardew Valley, there is no fascism, no war, often not even death. It’s calm, peaceful, and stress-free. What are we expecting games like this to give us? What do we need from them?

Related

What Alta is dealing with in Wanderstop is very clear and often emotionally confronting. The game uses the fixtures of cosiness to teach us that this routine, this slowness, can have a purpose. It teaches us that this calmness, the drive to cultivate beauty, can be used for something other than numbing our brains to what’s going on around us. Instead of tuning out, we can turn inwards, dissecting what inside us might resist calmness, trying to understand what it is that makes us want numbness.

And because of that, Wanderstop stands out amongst its peers. You can hide from your problems, you can try to dodge them by filling your time with tasks and busywork, but in the end, you always have to return to reality, to a world where you have to live with yourself. Will you leave the cosy game the same you’ve always been, or will you leave understanding something more about yourself? I can’t say I learned all that much from PowerWash Simulator, but I did learn something from Wanderstop.

Leave a Reply