Our Verdict

A unique premise, great sense of style, and a number of novel design concepts aren’t quite enough to compensate for Slitterhead’s repetitive mission structure and lifeless combat.

The first you hear when launching Slitterhead, the debut game from the Silent Hill, Siren, and Gravity Rush alumni at Bokeh Game Studios, is a chorus of voices rising in a dissonant sort of harmony. Some of these voices are deep, groaning in a low invocatory tone, while others are in a higher register, wailing quietly and unnervingly atop their counterparts. The variety of these voices represent a spectrum of characters – a group of people in uneasy communion with one another.

Very soon, the reason for this focus on community becomes clear. Slitterhead’s protagonist is entirely formless, a disembodied spirit called the Hyoki or ‘Night Owl’ that is capable of possessing any living being it encounters. Its exact nature is the horror game’s first mystery, with subsequent questions relating to the motivations of the characters it joins forces with to eradicate an emerging plague of paranormal creatures called ‘slitterheads.’ The Night Owl discovers and possesses these characters as the game’s story progresses and, because they differ from the nameless civilians (and, in one case, the stray dog) the spirit can also inhabit, they’re dubbed ‘Rarities.’

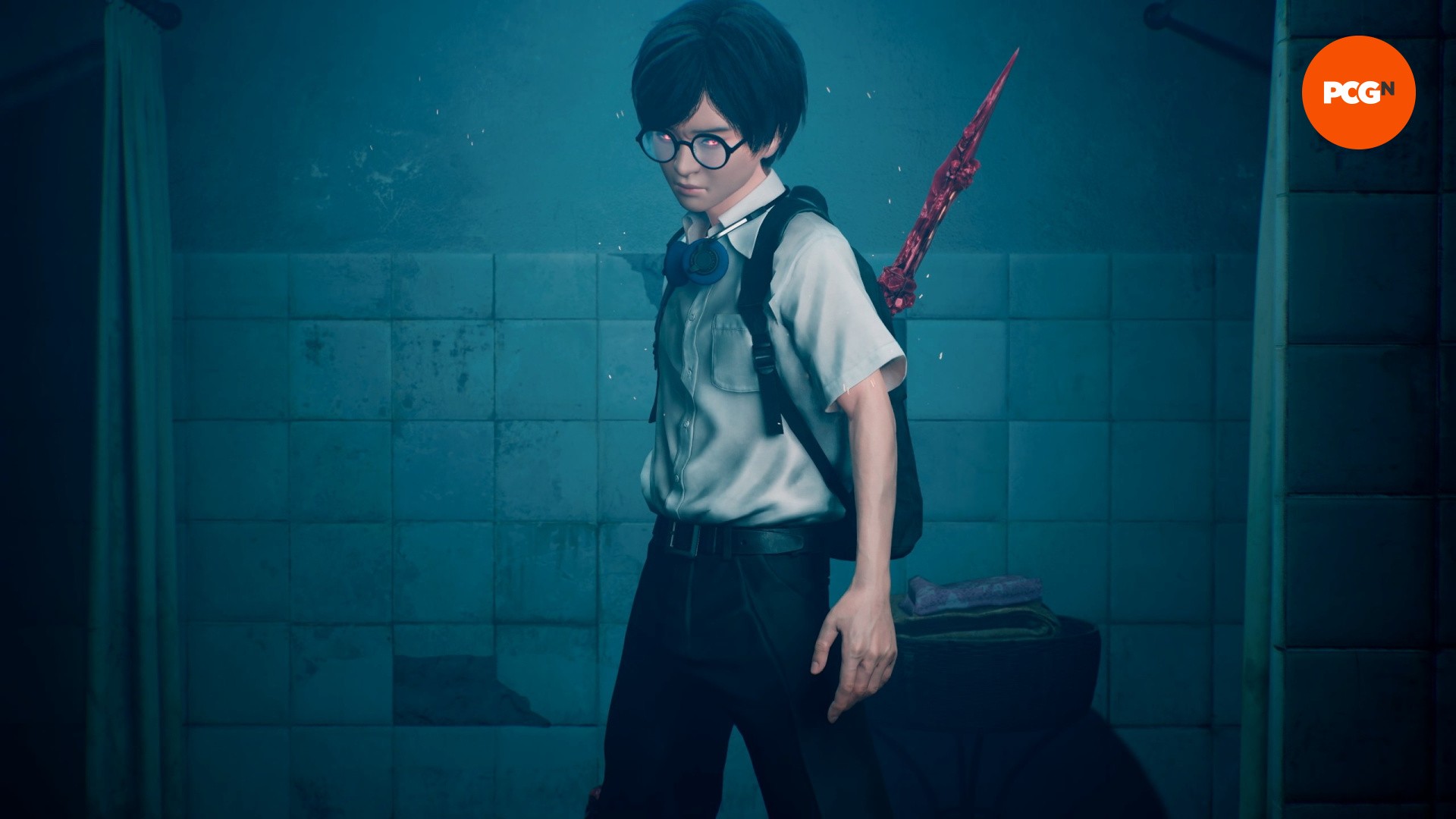

Night Owl’s possessions form the basis of Slitterhead’s game design, from exploration to combat. A typical mission, which begins after conversation scenes between Night Owl and the Rarities characters, can see two selectable Rarities – a bespectacled student, say, or a convenience store worker – heading out into the city alongside Night Owl to find a slitterhead base. Hit a button and Night Owl floats free of its host, yellow lights hovering above background characters and the two companions that indicate another body ready to inhabit.

You jump between these characters whoever fights break out. The Rarities are more defined, each equipped with their own skills, strengths, and weaknesses, which are lent, in part, to the civilians that join them in combat. All of these skills revolve around managing gauges that reflect their health, ability cooldowns, and weapon durability. Because the Rarities fight with hardened blood in various shapes – guns, boxing gloves, claws – combat becomes a balancing act between expending and regaining health by attacking, swapping between bodies, and recovering strength by holding a button to suck up the gore spilled in puddles from taking or inflicting damage. The game ends when there’s no living body left to jump into.

These battles are inventively designed, but they’re also largely unsatisfying in practice. Smacking an enemy with a hardened blood weapon, or taking a hit from a monster, doesn’t have much sense of weight and the parry system is similarly limp. The fights occasionally sing, the duo of main characters’ skills and body-hopping between nearby civilians working together to require quick-thinking strategies that capitalize on synergies. Mostly, though, the fighting is an unexciting chore that loses much of its excitement after you’re introduced to and have experimented with the full roster of Rarities.

Slitterhead’s exploration sequences are much better. The game’s setting, a city resembling Kowloon called ’Kowlong,’ is a dense network of streets, alleyways, and rooftops. It’s populated by everyday people going about their lives, shopping at open-air markets or having conversations beneath neon-lit storefronts, smoking cigarettes on balconies and sitting around chatting on patio chairs. When the slitterheads and their notably phallic ‘offspring’ begin a fight, emerging from their hiding places within an unassuming civilian’s body, these everyday vistas transform dramatically, folklore suddenly bursting out from the darkness of urban legend and into wriggling and violent reality.

While the body-swapping creates fantastic, low-key visual gags like a middle-aged man in work clothes getting possessed and gaining the ability to slingshot himself up onto the top of a sign or the edge of a building like Spider-Man, the premise of the slitterheads themselves doesn’t end up nearly as compelling as the possession-based design of Night Owl and the Rarities. Based on the yaoguai of Chinese folk legend, the game’s creatures appear as writhing conglomerations of wormy tentacles jutting out from the necks of otherwise human hosts. There are also more insectile varieties, like mutant praying mantises or people with giant sea horse-like heads, and each of them is appropriately gross and sinister, especially as the reason for their existence in Kowlong is revealed throughout the story.

Actually fighting and learning about the slitterheads, though, is a letdown. Aside from the lackluster combat, Slitterhead’s general structure is most to blame. The missions, which sometimes have to be replayed multiple times for time-warping plot reasons, parcel the plot out in fits and starts. It’s communicated through text-based dialogue scenes between missions, in ambient conversations overheard while fighting or exploring, and in brief cutscenes. Though the story starts off with plenty of intrigue-driven forward momentum, it quickly falls in and out of coherence as a result of this fragmented structure. Its characters are also visually distinct but too thinly drawn, making what would be dramatic twists and turns in the story fall flat.

This is all the more disappointing given Slitterhead’s excellent sense of style. Though characters outside of its main cast resemble lumpen mannequins with frozen faces, the Rarities and their primary opponents are much more striking. It would be a bad-looking game judged on fidelity alone, but its character design and crowded urban setting are colorful and distinctive. There aren’t very many varieties of slitterheads, but the ones you’ll face all look fantastic.

So, too, do certain cutscenes and menu flourishes. A character who’s extremely skilled in martial arts is introduced with a video that sees them dispatching a group of enemies, each of their hits accompanied by the initial crashes and booms of drums. As the intensity of the fight rises, the accompanying music builds from sporadic cymbals and snare rolls to a jazz solo-like tumult. Missions begin with character names and the day’s date splashed across the screen in swirling color, a TV-style trapping that’s furthered by many missions ending with a sudden freeze frame, a character’s face stuck in mid-movement with the colors drained and ‘To Be Continued’ displayed in bold font. The music, from longtime Silent Hill composer Akira Yamaoka (rejoining that series’ creator, Keiichiro Toyama, who serves as Slitterhead’s director) is also consistently inventive. Its score ranges from slick driving synths or plaintive guitar melodies to the title screen chorus mentioned above, all establishing a singular mood.

While Slitterhead is as multifaceted as that chorus of voices working together to moan its title screen music, its various parts come together as uneasily as the discordant song they sing. The novelty of its premise and its keen sense of style are especially welcome in an era of games dominated by remakes and sequels. It’s just unfortunate that the rest of the Slitterhead fails to live up to these qualities.

Leave a Reply