Real talk: as a deeply lazy human being, there are some games that I kind of secretly hope aren’t going to be my bag, because if they are my bag I’m going to have an awful time describing how they work. The problem with this is that the games that are hardest to describe are often the best games. They’re the games where you feel like you have a weird kind of duty to find the words for them, so you can tell everyone else how special they are.

LOK Digital

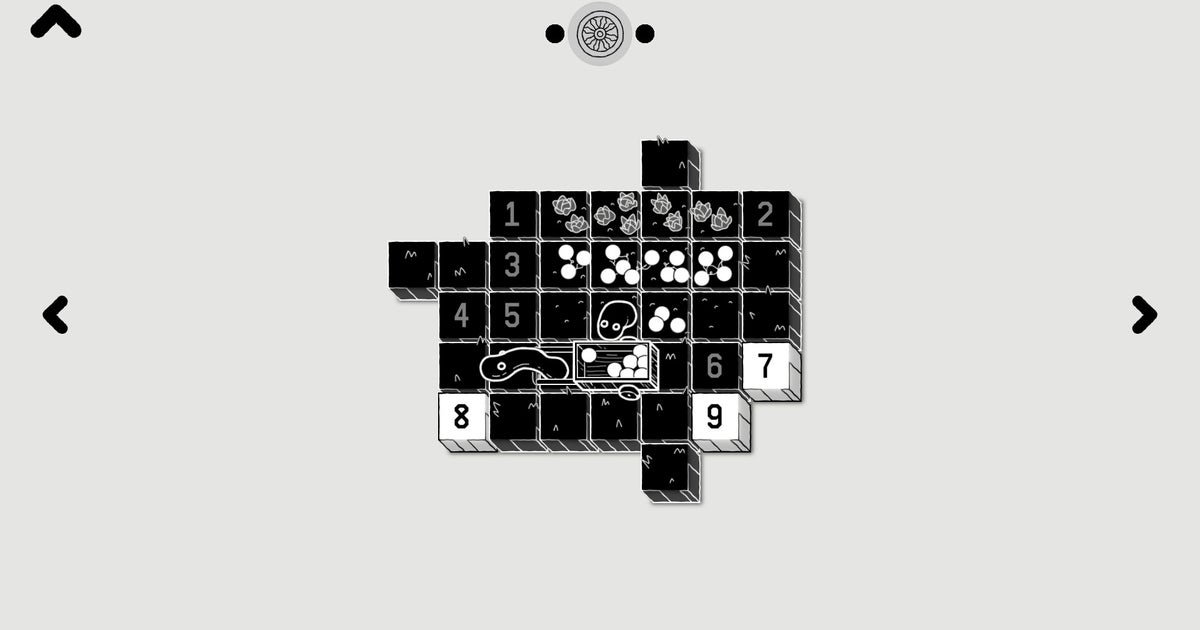

Anyway, Lok. Lok is fantastic. It’s a puzzle game about uncovering new words and then spelling them out on a grid. Words like LOK, TLAK and TA. These words all have powers, and this is where it gets confusing.

Your job in Lok is to take each grid you’re faced with and turn all the tiles black. If there’s a word you can spell – an in-game word like LOK, TLAK or TA, say – then you can black those tiles out just by spelling it. But these words then grant powers which help you black out other tiles. LOK lets you black out one more tile. TLAK, I think, lets you black out two tiles, but they have to be connected? TA, which I have just reached, well, I think TA lets you black out all instances of the tile you select. I think this is how these words work – I’m still at the point of testing theories with them all, and this is the kind of game where working out how it all behaves is part of the fun.

Maybe I’ve made it sound simple. Fine. It’s really not simple to play, though. This is because when you’re faced with a grid, you often have a handful of words you could spell immediately, so a lot of the game is about finding out the correct order to spell them in.

This order matters because once a tile is blacked out, it’s as if it isn’t there anymore. So if you have LOAK, you can’t use it to spell LOK, but if you black out the A, you can spell LOK. The game, for me at least, involves a lot of reverse-engineering. If I do this as my first word, where does that leave me? Which tiles can I safely remove, and where are the problems?

Over time, this turns into something properly magical. The game unfolds for me as a series of epiphanies. I’m stuck, but then I suddenly see a new possibility for a word hidden in the grid. How to free it? How to unlock it and its powers?

There’s a lovely line in The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon which I often think about with really good puzzle games. Oedipa, the protagonist, is examining clues and considering each one and “its fine chances for permanence”. The right clue, the right choice, comes with a kind of clarity. That’s Lok to its core. Maybe it’s not so hard to describe after all.

Code for LOK was provided by the publisher.

fbq('init', '560747571485047');

fbq('track', 'PageView'); window.facebookPixelsDone = true;

window.dispatchEvent(new Event('BrockmanFacebookPixelsEnabled')); }

window.addEventListener('BrockmanTargetingCookiesAllowed', appendFacebookPixels);

Leave a Reply