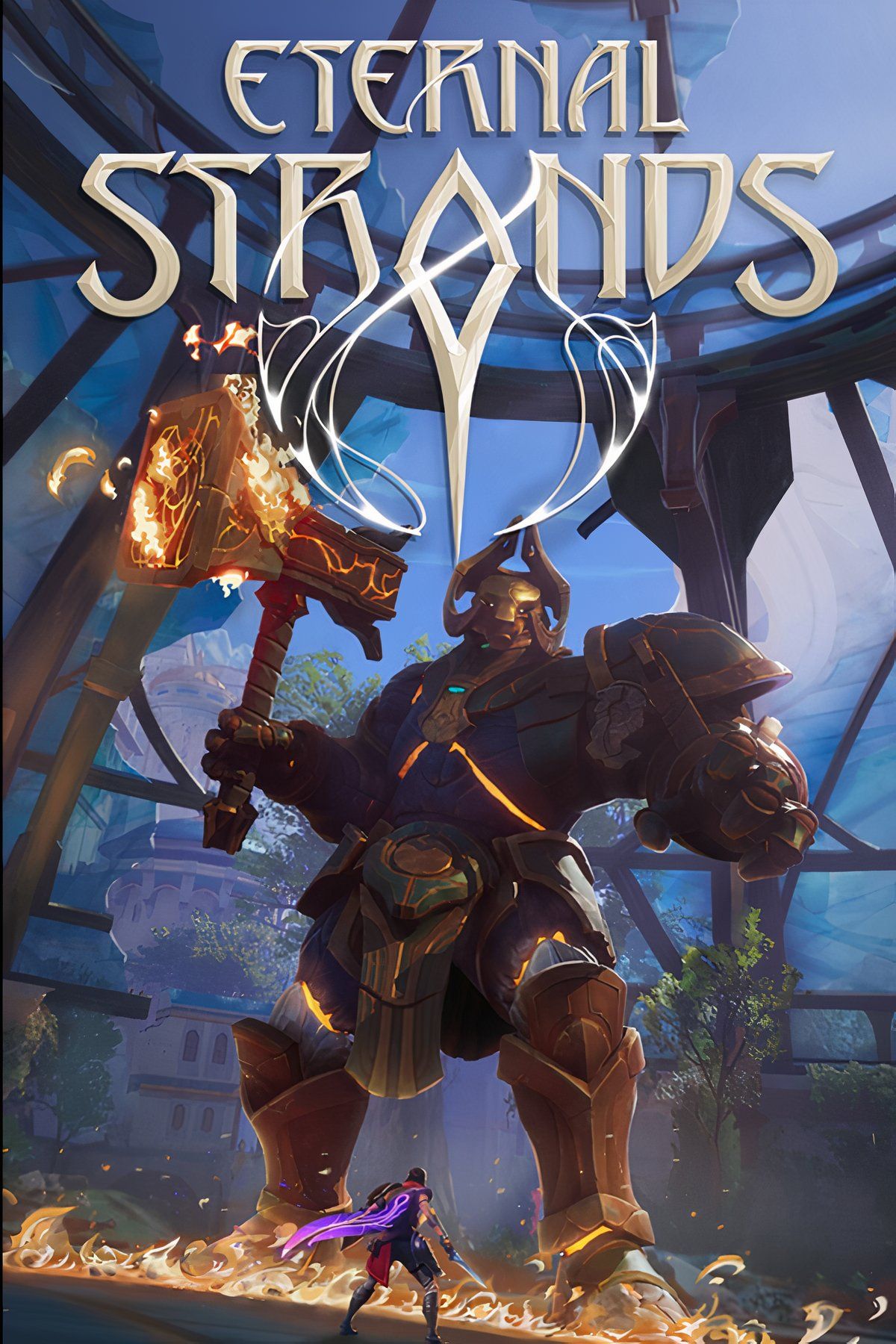

Yellow Brick Games’ debut title Eternal Strands has a lot of eyes on it given the pedigree of its developers. Following his departure from BioWare and a short stint at Ubisoft, Dragon Age creative director Mike Laidlaw and a number of industry veterans formed Yellow Brick Games. Among them is Frederic St-Laurent, Eternal Strands‘ co-director and lead designer of Assassin’s Creed Syndicate. Alongside their team, St-Laurent and Laidlaw have shaped Eternal Strands into something that aims to impress players with its emergent gameplay and freedom of expression, and an upcoming demo launching on January 21 will give its audience a small taste ahead of the game’s full launch on January 28.

In anticipation of the demo’s release and players’ first hands-on experience with Eternal Strands, Game Rant had the chance to sit down with Laidlaw and St-Laurent to talk about the game’s development, how Yellow Brick Games’ veteran staff helped steer the ship during the turbulent shifts that came about due to COVID, and what players can expect from the complex physics-based systems that form the foundation of Eternal Strands‘ gameplay. The following interview transcript has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Related

Every Feature Confirmed for Eternal Strands So Far

Eternal Strands is an upcoming action-adventure game from Yellow Brick Games, a studio comprised of BioWare, Ubisoft, and overall industry veterans.

How Yellow Brick Games’ Collective Experience Shaped Eternal Strands

Q: How does it feel to have Eternal Strands’ launch right around the corner?

Mike Laidlaw: It’s been really interesting. I think, because Fred and I have both been involved kind of from the beginning, there is this sensation of thinking and hoping that we have managed to stick the landing on what was not just a leap of faith, but given COVID and everything, it was sort of like a backflip of faith.

Things went a little sideways very quickly. It was a really interesting time where suddenly everyone was investing, now no one’s investing, and moving from publisher to self-published…all of that has been just a positively wild ride. Yet, I think we managed to thread the needle and steer our way to a ship. For me, honestly, it’s a sense of pride. I believe I’m happy with the game. I’m very pleased with the game, but even if I weren’t, having successfully navigated all those challenges and still have an operating studio with pretty high morale is a huge success.

Frederic St-Laurent: On my side, I’m really happy. Mike and I can really speak for it because we were there, like you said, from the beginning, but we stuck to the vision we had four years ago. What we’re delivering is, in terms of design intentions, it’s about the player having tools to express themselves through combat and creating some things, finding their own strategies and stuff. It’s what we really wanted to do with a physics-based game, and we delivered that. Now I’m at the stage where it’s like at the end of a pregnancy. It’s like “The baby needs to come out! Okay? I’m done with this. Please, please finish it.” [laughs] There’s an anticipation behind it for sure.

Q: From the initial concept to the final product, how has Eternal Strands grown and expanded throughout its development?

Laidlaw: For me, it is a project that kind of went through one major evolution, right? A Pikachu to a Raichu. When we first started, we were leaning more toward a Monster Hunter-type game. We were leaning a bit more heavily into the “go out hunt monsters” kind of loop that you find in a Monster Hunter-style game. Over time, we found two major things we wanted to change out of that formula to move us closer to something in the Breath of the Wild space, except we held onto parts of the Monster Hunter formula. You still come back to a base camp, you still sort of have the sense of an expedition, but there’s more of a story. There’s more of a quest. There’s sort of a goal that that brings you through, so it’s a little less purely like Monster Hunter.

Of course, Monster Hunter isn’t purely about progression, but it is much more heavily skewed to progression than, say, the Shrine collections and story things. With that change, we also realized there was a chance to sort of evolve away from being more limited in terms of what you could do on any individual expedition. We opened up the opportunity for the player to take all the Strands with them. For instance, you originally had to pick between Telekinesis, Frost, and Flame. We instead changed that to you being able to take all three and mix and match them. That was an evolution we did based on our alpha playtests, internal feedback, external feedback, etc., and we just sort of said “You know what? Cool. Let’s open this up for players, give them a lot more variety in what they can do.” Things clicked very hard when we did that.

I think that was, in part, because it wasn’t like you were going out for short little jaunts, you were going out for larger, more quest-based jaunts. The longer you were out there, the more you wanted to have sort of a larger toolkit. It was a healthy evolution for the game, but otherwise, a lot of it is very similar to sort of our original proposal — the physics, the large creatures, climbing…all of those elements are very much what we intended from the beginning.

St-Laurent: Removing focus on the planning of selecting gear and selecting magic powers and stuff, just removing that heritage that we had at the beginning ended up still being more of what we promised, which is emergence through mixing powers together, synergies, and stuff. Once we removed the element of “Oh, you need to pick only one,” you had like a Swiss Army Knife and you could just mix more and more of your powers together. Which was one of the pillars of our game, the emergence.

Q: So that expansion of the player’s toolkit kind of took things from being more granular to making it more holistic?

Laidlaw: Yeah. Every bit of progress you made was towards every expedition, getting stronger and feeling like your range of possibilities was expanding and growing. That was, I think, a really healthy change for the game. I think it’s important to find the balance in any creative endeavor between not jerking the wheel like you’re driving in Dukes of Hazzard or something, but instead, the sense that you need to keep a reasonably steady course but also be flexible enough on feedback to know when it’s time to course-correct, threading the needle between randomness in your design and overt dogmatism. You need to know when it’s time to make some shifts.

It’s been a healthy process. We probably could have made that change sooner, to be honest, but I think we did it in time for it to land and for it to be a comfortable experience for us, to be able to run all through all the way to beta playing under a new paradigm.

Q: Yellow Brick Games is a studio comprised of several industry veterans. Were there any experiences from previous projects that proved vital during Eternal Strands’ development?

St-Laurent: Of course. Mike just talked about the narrative, but Mike’s and Kate’s background—Kate was on the narrative side of an Assassin’s Creed game, and also Mike at BioWare, on Jade Empire, and also this other game, “Dragon Age”? [laughs]

That has proven to be an amazing, amazing head start already, just on day one. A lot of people came in from Ubisoft, me included. In terms of the action-adventure part of it, you could think of Immortals Fenyx Rising, Assassin’s Creed, The Division, Rainbow Six…just the progression, the minute-to-minute gameplay, the tactics, and the decision-making definitely helped us to shape up our combat and determine what happened in every second of gameplay.

Laidlaw: I think the other things to call out are that, by making sure we had a pretty strong bench of veterans at the studio before we started bringing newer folks in — and we’ve hired a number of our interns and stuff, which is cool — but having the veterans in means that we had a little more discipline, I think, than some indie studios might have in terms of project management, how you handle costing a user story towards development against a milestone.

That kind of stuff is…you not only have to learn how to do it, but there’s also the experience of having seen the benefits of being able to sort of be predictive about the schedule, being able to make cuts where necessary, being able to make changes where necessary, being able to prioritize. All of those things are discussions that I think some degree of maturity is required, and some degree of experience to have seen how it really plays out is beneficial. That’s helped us really kind of stick to our schedule and try to land the game where we thought we would, as opposed to sort of overrunning for a year or something extra.

Q: In terms of having the experience and the know-how to predict how things logistically will play out, did that play a major part in the project not falling apart in the early stages due to COVID and other factors?

Laidlaw: It did definitely with operational maturity and flexibility. But also, you know, it was interesting to watch remote work really become mature and become less of a scenario where it was like “Oh, okay. This is something that one or two people do.” Everybody suddenly gained experience with remote work and how to maintain proper discipline in meetings, how to actually try to keep some sense of company culture, despite the fact you can’t always go into the office and hang around the water cooler, you know, if you have one. We still have one, we don’t use it that much. [laughs]

But it’s created a really interesting shift. I think if we were going to found something new, doing so while things were somewhat turbulent was not necessarily…it had challenges, but I think it was about the best possible time to be starting something new and looking at different operational parameters because it made us very comfortable with things I think might’ve been harder to adapt to, such as “Okay, cool. We have multiple people working out of Spain. We have folks in Vancouver. We have folks in Toronto.”

Having these folks that are remote and knowing that actually can function as long as everybody’s pretty disciplined about when meetings are booked and how you arrange those things created a really interesting scenario where you had to learn how to work within that framework regardless of geography. And then it’s given us some maturity now, even, where — yes, there is a hybrid office, we have folks both in Montreal and Quebec — but we’re able to very comfortably still work with people who are remote or hybrid, like myself. I tend to be at home most of the week, but I go in for a day or two here and there and that can work really well. It lets people play to their strengths.

Balancing Eternal Strands’ Gameplay and Narrative Elements

Q: Mike, given your legacy as the creative director for the Dragon Age series, can players expect a similarly narrative-driven experience in Eternal Strands?

Laidlaw: There is a narrative experience in Eternal Strands, but I think I would want to very stridently qualify “similarly” narrative experience because, to me, Dragon Age and CRPGs — You know, the stuff coming out of Obsidian, obviously Larian, and so on…I tend to feel that those games are built around sort of the concept of dilemma, right?

A lot of role-playing comes out of having to make a tough choice and choosing between sides or factions, characters, or what have you, right? So there is a dilemma that must be resolved. That’s coupled with the mechanical progress and leveling that comes out of the RPG systems, right? You could say that a Telltale game had the dilemma, without this sort of mechanics.

In our game, I would say we aren’t focusing on the dilemma. What we have is lots of mechanics. We have a large cast of characters. We have a lot of interactions. There’s a fair amount of writing in the game. I think our script just for voiceover came in over a hundred thousand words, so there are lots of chances to talk, but it’s not like “Oh, you must choose between A or B” so much as a focus on more reactive options and reactivity.

Being a game that we knew was going to be more action-y and would focus more on this idea of “Hey, go out and hop on a dragon’s back and cling to it as it flies around,” I didn’t want to burden the game with large, heavy storylines. Instead, while there are quests you pursue with dialogue, there’s also an option that “lives” on most of the characters called “Talk,” which is sort of sometimes on and sometimes off. Essentially, “Talk” is they want to react to something that happened in the game. A story beat occurred, you achieved something, you went somewhere, that kind of stuff. It’s completely optional for you to click it. And if you do, you will get a little scene where they sort of respond to the things that happened throughout the game. It’s a little more inspired maybe by something like the Fire Emblem games and things like that, where it’s sort of an optional encounter for you to have.

I think people like them. I like them. I liked writing them. They’re a lot of fun because the characters just have character-ful moments., so I would say there’s a narrative. There’s definitely a story, which is sort of a bombastic, almost fantasy version of The Mummy or Indiana Jones, but it isn’t a story like Dragon Age in that it’s full of dilemmas and tough choices and heavy branching, things like that.

Q: So narrative is still an important component, but it’s something that players can choose to engage with rather than it being a core element of the main gameplay loop?

Laidlaw: Yeah, well, there are quests and you’re pursuing the quest to give context for “Why am I going out into this place? Why am I hunting creatures? How do I feel like there are stakes? Why do I feel like I achieved something? Why do the credits roll?” That’s all there, but then there’s the second element: completely optional reactivity, which, for me, was a lot of fun. It’s a chance to be like “Hey, if you would like to opt-in on more characterful stuff, if you’d like to do the quest that the characters have for you, you can, but you can beat the game without them as well,” right? And if you want to, if you’re more of an action player, that’s cool. We’ll just give you some purpose, and we’ll be like “Hey, here’s the threat. You should probably go deal with it.” It’s sort of a hybrid. But even games that are quite action-heavy, I still think they benefit from having some sort of story, right?

It’s like, “Why am I here? And what am I doing? Whose butt do I get to kick? And why do I want to kick it?” You know, important questions that drive you forward. As far as I’m concerned, if a player wants to play through Eternal Strands and be like “I’m just going to do the critical quests,” they’re clearly labeled as such, rock on! I still want that to be a good experience for players. I want them to feel like it all hung together, but if they want to do all the side stuff, that’s there too.

What Players Can Expect From Eternal Strands Given Its Influences

Q: Early coverage for Eternal Strands saw games like Shadow of the Colossus, Breath of the Wild, and Dragon’s Dogma cited as inspirations. Can you walk us through some of the various elements from these games that players might pick up on in Eternal Strands?

St-Laurent: I can start with Shadow of the Colossus. We have huge respect for what they did years back in terms of physics-based characters climbing giant creatures. That’s always been something that we were looking to do our own version of, so that’s what we went for. You can literally climb on 25, 30-meter-high creatures or, like Mike said, jump onto a flying dragon and seamlessly climb all over it. It’s not quite like other games where there’s a targeted point that you can latch onto or something like that. You can seamlessly go over the whole model of the creatures that we have. Because they’re also driven in physics, you can pin them down and that’s going to affect the way they move, so that’s also a big differentiator compared to other games, which are more kinematic-driven or animation-driven.

If you put ice on a giant monster, parts of him are going to weigh a lot more. The way it’s going to walk then is going to slow him down. His arms are going to drag on the ground. If you pin the whole leg down to the ground, then he’s immobilized, he’s going to try to break free. You’re going to have a few seconds to do something else, to plan your next move. That was kind of the idea. Although Shadow of the Colossus was level and puzzle-oriented, the vibe of you having this sort of asymmetrical combat…we wanted to still have a sense of that, but we went at it from a combat perspective, not a level design perspective. Shadow of the Colossus did that pretty well in terms of “You need to find a way to get to this point and then get to this other point. Then look at the windows of opportunity when they shake, and then continue your way up.” Ours is more like “Okay, move around, smack the arms enough and the arms are done, you need to move somewhere else to damage the health bar. Shoot arrows from afar or throw back fireballs.” There’s more of a combat element than a puzzle design one.

Laidlaw: And I would say that probably is where Dragon’s Dogma helped kind of shape some of our game because Dogma also lets you climb on the ogres and the dragons and so on, but it approaches it more from an action RPG standpoint. I’m doing hit point damage, I’m inflicting status ailments on foes, that kind of thing.

I would say, when we look at Dragon’s Dogma, it brought in a bit more narrative, some more quest lines, that kind of stuff, and had this element of “Hey, I’m going back to Gransys and I’m going to rest and recover my health, then I’m going to go back out.” That sense of expedition and then coming back home and sort of resting up.

We approach it a little differently, of course, but that particular element of Dragon’s Dogma is quite present. Obviously ,there are some differences. We don’t have the Pawns and a party, we want to focus on Brynn as a sort of solo adventurer. But then what’s interesting is you take our kind of expeditions, which are pretty long field explorations — and then we introduce camps, which let you stay out for quite a while, which is cool — but we were kind of drawing inspiration from this sense of “the expedition,” which dovetails into the micro-expeditions that are very targeted like you get in Monster Hunter.

I would say, Monster Hunter…we’re not spot-on Monster Hunter, but the kineticness of the creatures and so on is a big part of Eternal Strands. I think, honestly, Monster Hunter players are going to be very familiar with how we’ve decided to do progression. This is Fred’s system, so I’ll let him talk about armor and crafting and everything.

St-Laurent: For sure, we don’t have an XP system, so it’s not by completing quests and earning XP that you level up. It’s all based on loot and on gear that you craft. You don’t find any weapons or armor in the game. Everything is crafted by your crew at the base camp, so what you’re doing is defeating the monsters and finding the emergent ways you want to defeat those monsters. This allows you to put your hand into the loot tables because if you burn, let’s say, a hound or something, then all the fur-type loot is going to be destroyed in the process. Instead, you’re going to get more leather and stuff like that, or even bones. If you go for enemies that are made of metal and you use ice, you brittle them and they break, then you’re going to shatter all the metal components you could forge or carve. Instead, you’re going to get more leather or cloth.

If you’re looking for certain things, you’re going to go for certain monsters and you’re going to defeat them in certain ways, and then you’re going to bring those materials back to base camp. You’re going to have blueprints of gear that you’re going to find in the world that you’re going to also bring back. The blueprint is going to say “Oh, this armor is going to be light, and it’s going to be shaped like this.” What materials do you want to use? “It exclusively uses leather and cloth.” Which cloth? Which leather do you want to use? That changes the color. That changes the stats. The better the leather, the better the cloth, the higher the stats. That’s how you level up your character and their internal strength.

Laidlaw: Yeah, so putting a focus on player skill, learning creature behavior, learning their timing, learning how to break things and — just to expand on it, because Fred did a really cool thing here — when you break stuff off of creatures, these things can drop materials. There are multiple ways to take them out as well. You can choose to go through a more complicated combat loop in order to harvest their Strand, which allows you to then weave their power into your Mantle. That’s how the new powers are acquired. You don’t have to do that endlessly, it’s more sort of three times, kill them once, and then harvest twice, which adds a layer of challenge.

When Fred’s talking about manipulating the loot table, there are certain parts on even the big guys, where if you make them super hot before you break them off, they sort of refine themselves and they drop slightly higher-tier materials. I think that’s going to be the kind of thing players slowly figure out over time as they’re manipulating the temperature. The counterpoint is using cold. You can pin enemies in place. Once they’re pinned in place, the cold can make the metal brittle and much easier to break. So do you make it hot, then cool it back down? Are you at the point where you’re literally doing thermodynamic chemistry mid-combat? If so, if that’s your ultimate play style, that’s a win.

St-Laurent: Since the vision has always been to foster player creativity in defeating monsters, I didn’t want it to be like “Oh, how can I be creative to defeat them the fastest?” You can do that, be creative, and find a way to say “Okay, with this combination I can take them down in two minutes, it’s super easy,” but that’s not how you’re going to progress more in terms of the loot.

How Eternal Strands’ Physics Systems and Open-World Design Shaped Its Gameplay

Q: Brynn’s elemental powers and abilities to manipulate the Enclave are one of the cornerstones of Eternal Strands’ gameplay. What were some of the challenges in designing an open world that could also essentially be utilized as a weapon?

Laidlaw: [laughs] All of them! They were all challenges.

I’ll start and then Fred can probably add some texture to it. To me, the first was to go very heavily into destruction, which is challenging, right? To be able to rip out pillars and chunks. We’re not ripping entire buildings out like Battlefield, but at the same time, there are pagodas and there are small houses you can actually smash, that the creatures can smash, which adds a lot to it. That was a big, big part of it. Of course, having those things have physical impulses meant they need to have weight, they need to have properties. They need to have all this data driving them to be able to say things like “How heavy is this? What kind of things can throw it?”.

Then the other big challenge, I think, was developing a dynamic thermodynamic system where heat will not just exist in the world as “it’s a d10 fire damage,” but it’s actually this amount of heat crossing a threshold. Players who’ve played Breath of the Wild will know there’s that little meter that shows you how hot Link is getting. Our entire system is based on that too, where you aren’t just standing in fire, so you’re dying. You’re standing in fire, which is causing you to heat up, which is what’s causing you to die.

You can wear more resistant stuff, so it increases your threshold. You can inject ice into the world using Frost magic and visually see it, like “Oh that’s less hot here than it is over there because that’s bright orange and this is dipped back down to black.” Certain enemies are responsive to it; cold can remove the sort of “chameleon stealth.” Fur-covered creatures tend to burn much faster and take more damage, so then you add the physics of moving them around and say “Okay, I can fling you into this fire and do this, or I can use this ability that causes elemental effects, the Frost and the Flame, to actually concentrate, and when it goes off it emits even more heat,” right? There’s almost sort of these inherent combos, but the combos are kind of based around this sort of physics system where we’re treating the heat as if it’s something you can manipulate and move around using certain abilities. So, all of that is complicated.

St-Laurent: Instead of going for more of the classic recipe, which would be: you have this power. How does this power interact with this object, this object, this object, this object, etc.? We go with “Here’s the power, here’s the simulation, physics-based and thermodynamics-based, so heat and cold. How does this power speak to this, and then how does the object in the world speak to the simulation?” That means we needed to come up with the same formulas as you have in physics. It’s like, “Oh, I have a material. This is wood. Wood has these properties. Its combustion point is at this temperature, weight is this per centimeter cube. Does it feel right when I lift it with an early-game Telekinesis? Does it feel like wood? Does it bounce like wood? Does the friction look like wood?”, and then finding these parameters for everything in the game, for every material.

Hopefully, what we did is…we have, not a big list, but a fair list of material. Everything in the game is assigned to those and naturally, with their volume, they just end up being automated to fit their material. If you have a small stone or a big wooden pillar, then one might look bigger, but it’s going to combust and the other one won’t because the combustion point of it (or it’s more the radiation point of the stone) won’t be reached until this many degrees. Then, when it does, it becomes red-hot and stays that hot for quite some time. If you move it around and throw it in the grass, it’s going to start a burn, same as this wooden pillar is going to emit heat when it burns. But when it’s done, it’s done.

That was the main challenge, trying to find this recipe for everything. When it was settled, it was more a matter of applying this recipe to everything and then seeing what the outliers were. Which materials are the ones that, even though this is supposed to be working, we’re going to manually go in and adjust? I think that was our challenge, to allow for emergence. Because I didn’t want to have it be like “Oh, I use Fireball. Fireball does this and that, and that’s it.”

Laidlaw: Yeah, going fundamentally systemic was the only thing that made it possible. “This has weight, it can be moved, it is breakable.” Knowing that everything has those properties and the properties are shared meant that we could have those pleasant discoveries where it’s like, “Oh yeah, cool. That responded appropriately.” But even then, there are still months of tuning to try and make it feel right because sometimes the real physics is not fun. Sometimes you just need to make it awesome to throw. And that really does come down to testing, feeling, playing the game lots, and so on. But I do think that systemic approach has helped us a ton to be able to have the systems be tunable from the get-go.

St-Laurent: Oh, it’s still arcade-y. We don’t need to think about simulation as trying to produce the real thing because you would be surprised how much a rock like this [holds up hands about the size of a basketball] weighs. [laughs]

Laidlaw: It’s maybe somewhat heavier than in video games. You need a little arcade in your simulation to keep it a little zany.

Q: Is there a critical path for players to follow in Eternal Strands or is the game more non-linear in terms of how players choose to explore the Enclave?

Laidlaw: There is a critical path set of quests that you would pursue, and each of them is designed to basically build upon the story and motivate the next thing that Brynn is going to tackle. It’s not completely linear. There are periods, especially after Brynn reaches the capital — which is quite early on, not to spoil things, but it’s going to be right after the demo — when the game sort of opens up and gives three or four possible avenues of exploration for us to try to figure out what happened here.

The game starts a little bit didactically, in part because there’s a fair number of systems for us to teach, like how crafting works, how upgrading your gear works, that kind of thing. We do start on a reasonably linear path, but it does open up quite a bit. What’s nice, as well, is that the story is sort of designed to throw you into different zones and keep you moving around.

We’re hoping that the natural urge for loot, and the fact that there are these large epics (what we call both the Arks and the great creatures like the Ashpeak Drake) flying around or walking around, that you have these sort of serendipitous encounters where you’re like, “Well, I was doing this quest, but there’s a dude throwing fireballs at me, so I think I’m going to pause on the quest and deal with that.” You could run away. Totally valid, right? They’re just on patrol. They’re not out to get you. But once they have you in their sights, they are going to chase you for a while. But also you might be like, “Hey, this is an opportunity.” Maybe I’m looking to harvest. Maybe I’m looking to get some loot from them. Maybe I just want them to not be walking around this level anymore. Maybe I want to test out this new sword. You name it. We try to keep things reasonably free-flowing on that front.

But yeah, there is a path you will follow to get you through the story. There’s a moment in which the credits roll and you say, “Cool, I won. I beat Eternal Strands.” It is sort of a complete experience from that point, but it’s not completely linear and there are a lot of neat side objectives as well as, of course, the companions who each have their own little story arcs that you can pursue, which are optional. You don’t have to do those at all. They aren’t even heavily loot-gating, though a few do come with some game rewards. Like when you do the Blacksmith’s arc, she learns to make new armor. Not the only armor in the game, but just one of the, like, 10 suits.

St-Laurent: Those companion quest lines are awesome. They’re not like an afterthought, but they are indeed optional. But in terms of…if you only do the bare minimum to reach the credits, then for sure you’re going to miss a ton of nice stuff.

What to Expect From Eternal Strands’ Upcoming Demo

Q: Eternal Strands has been touted as a game that players need to “feel” to truly understand what it offers, as well as a game that emphasizes telling players “yes” instead of placing limitations on their expression. Knowing that, what can players expect when the demo launches just ahead of Eternal Strands’ release?

Laidlaw: So, the demo is going to basically take you through the opening of the game. You’ll get a chance to start the adventure. I believe you’ll be able to keep the progress you’ve made as well…

St-Laurent: Yes.

Laidlaw: …Which will be great for players that start it and are like, “Oh, cool. Yeah, I want to keep going.” Essentially, we’re going to ease you in and sort of give you a crash course on how the systems work. As it opens up, it’s going to give you a chance to feel the early game experience. Throughout the demo, you can acquire two additional powers, you can find new armor, you can craft new armor, you can progress into the story, and you can assemble Codex entries. We have a system where you have to gather the component pieces of evidence that allow your lore keeper to assemble them. You’ll get, I guess, your first sort of sense of the Enclave and the world that the Enclave itself finds itself in, as well as get a chance to meet, and interact with, the whole party.

I think, for me, what it should do is let people get a sense of how free, and occasionally frantic, the combat can be, how big the epics are, and the fact that you can absolutely leap on a dragon mid-flight. If you happen to pull that off, you go right ahead and enjoy. The Drake is…he’s a fun fight.

I think probably the big takeaway for the demo is I would like people to be able to get an honest sense of what the game’s going to be like as they play it. I’d like them to evaluate it on its own merits. This isn’t a hyper-realized $90 game; this is a $40 game. It was made by 60 people. It’s not a multi-thousand-person studio kind of thing. It’s not a Dragon Age, it’s not a Ubisoft game. It’s just its own thing. It’s this cool little indie thing we built, and we hope people enjoy it.

But I think that if people are playing and going “Yeah, this is for me,” a demo’s a great way to sort of make that evaluation and say, “Yes, this is something I really would like to dig into.” I hope people come away with an honest impression of it and go “Yeah, I want to go further with this.”

St-Laurent: The only thing I may add to this wonderful answer is that I hope people start to have a glimpse of how it’s really up to them to create their own fun with the tools we provide. Because that was our goal, trying to give them tools to create emergent strategies. I hope they find things I haven’t, like how to defeat certain things and combinations and synergies that they’ll be able to show off on streams and videos. Even with just the first two hours of the game or something that they can play through in the demo, if some can get that sense of “Oh, okay. There’s going to be more of that?!,” I would be very pleased.

[END]

Leave a Reply