Crashlands 2 is Butterscotch Shenanigan’s long-awaited follow-up to its quirky sci-fi exploration game that refreshingly sidestepped many of the more frustrating and tedious survival game features. Like its predecessor, Crashlands 2 drops players into a vibrant alien wilderness to explore various biomes, gather resources for crafting, and encounter an assortment of unique and occasionally hilarious alien creatures. While that may sound like the description of a typical survival game, Butterscotch Shenanigans intentionally left out aspects like inventory management or starvation, leading to a “thrival” game rather than a survival game.

Game Rant recently sat down with Butterscotch Shenanigans creative director and co-founder Sam Coster to discuss the team’s approach to a comprehensive Crashlands sequel. He went in-depth on how virtually every aspect of Crashlands 2 is a significant upgrade over its predecessor, with a massive visual overhaul, entirely revamped combat system, and far deeper interactivity with the game’s myriad creatures. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Related

Crashlands 2 Creative Director Talks Why It’s Not Really a Survival Game

Game Rant chats with Butterscotch Shenanigans creative director Sam Coster about how Crashlands 2 is a “thrival” game, not a survival game.

How Crashlands 2 Builds On The Original

Q: As a sequel, how does Crashlands 2 build on its predecessor? Are there features from the original you wanted to expand on?

A: I think with sequels, people either go the “more of the same” route or try to get at the DNA of something and translate it into a slightly different set of systems and mechanics. A big example is Zelda transitioning to Breath of the Wild—it still feels like a Zelda game, but it’s not what the previous ones were. Yet, somehow, it still is that game.

With Crashlands 2, we really focused on that spiritual successor aspect—drilling into what made the original special and seeing if we could translate that into a bigger game. We wanted it to grow alongside our audience and make something that works for where they’re at now, as well as where we are as developers.

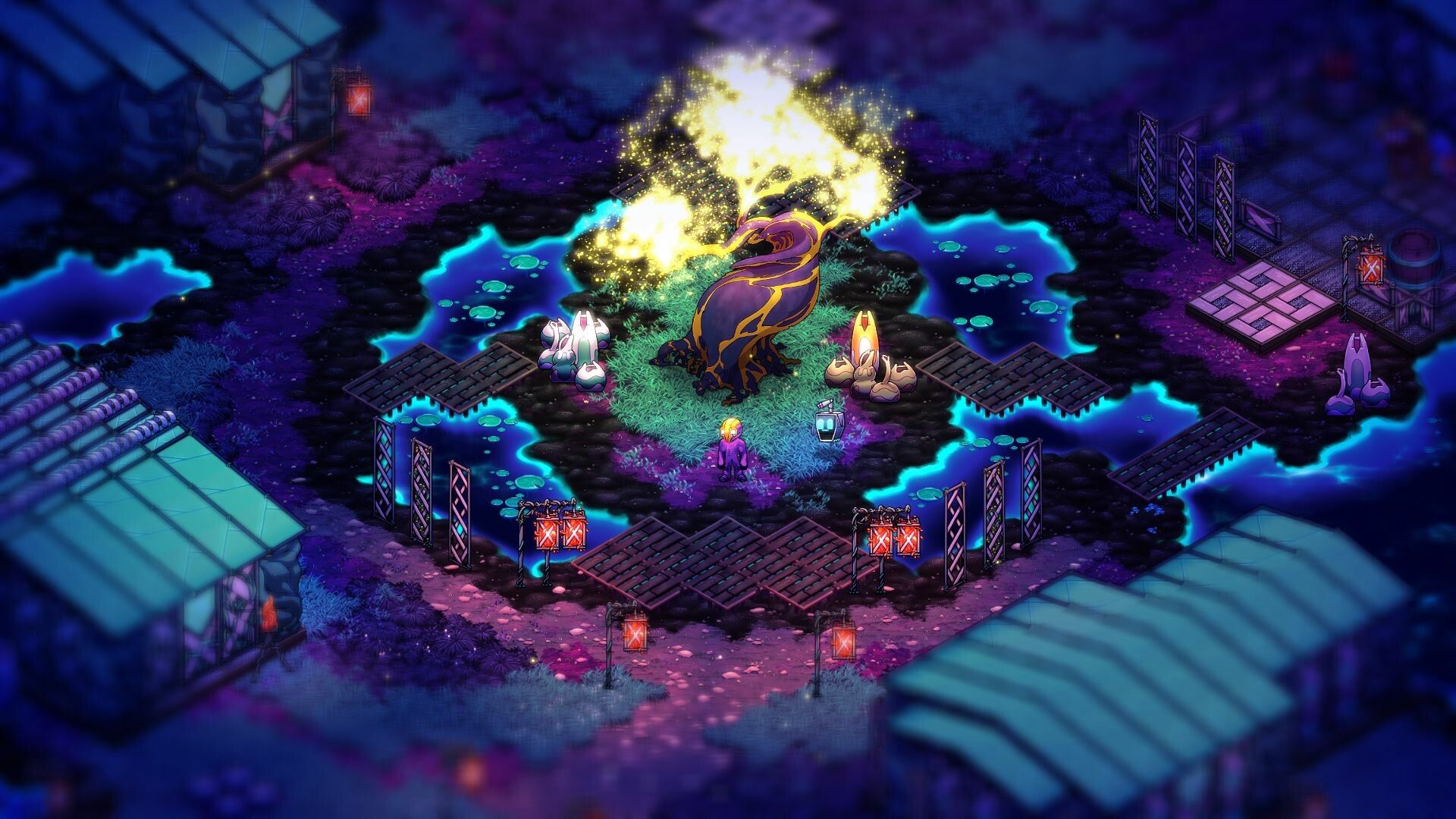

We kept all the features at a high level, but every single one has been completely reworked. Base building is a great example. In the original, you could only build knee-high walls—there were no roofs, none of that. But with the switch to an isometric view, we were able to add a lot more depth. Now you can fully build structures with roofs, and that system even ties into crafting and research. As players explore, they’ll find buddies in the world—essentially alien roommates—who move into their house.

So we still have base building, but it does so much more. It’s basically what we wanted to do originally but didn’t have the skills or tech to pull off. And really, that applies to everything—we revisited every system in the game and revamped it in that same way.

Q: What would you say is Crashlands 2’s biggest addition over its predecessor?

A: It’s hard to pick just one, to be honest. As I said, every system has been completely overhauled and cranked up to 11.

I think the most interesting change at a fundamental level is how the world is built. In the original, we used procedural generation to create the world, and then we had these custom areas—what we called outposts—where all the quest content was placed on top of that procedural base. In Crashlands 2, the entire world is hand-built.

That shift makes a huge difference. Internally, we used to joke that the original game was designed to favor wandering. You couldn’t purposefully find a specific thing or reach a certain location in a structured way. Even filling out the fog of war on the map lacked a sense of discovery because there weren’t really any true nooks and crannies—it was all procedural.

One of the biggest challenges was switching to an isometric view and deciding to hand-build the entire world. That allowed us to create the feeling of truly exploring an alien wilderness. It also allowed us to push the ecology aspect further since we had complete control over how things interact. Now, creatures actually hunt and kill each other, and plants and resources have dynamic interactions.

There’s just a lot more ecology and authored content shaping the world. In a way, we took the best parts of the original game, jettisoned everything else, and focused entirely on making those parts shine. For such a small team, that was a huge challenge.

Q: Were there any lessons learned from the first Crashlands that you applied the second time around?

A: I think the procedural generation change highlights the difference between wandering and exploration. It might sound like splitting hairs, but it’s absolutely not when you break it down.

Combat is another big one. In the original, we wanted players to have different play styles, so we had three weapon types—axes, swords, and maces. However, since the input scheme was so limited—just a simple one-touch system for moving and interacting—there wasn’t much room for depth. Players couldn’t evolve their playstyles or specialize in a way that felt meaningful.

One of the big lessons we learned was that if we wanted deeper combat, we had to loosen some of those restrictions. In Crashlands 2, we added more functionality—more buttons, and more control. Now, if you’re playing with a controller or any other input method, it’s not just about pointing in a direction and going. You have an aiming reticle, different telegraph sizes, and all kinds of funky stuff we did with abilities.

That shift makes playstyles feel distinct. All three of us brothers gravitated toward completely different builds in our playthroughs. We’d compare notes after playing for 24 hours and be like, “Oh, I used all this stuff, but you guys used that? That’s wild.”

It’s a huge difference from before, where we had to hope players would feel a distinction between weapons—even if, deep down, it wasn’t quite there. I’m excited to see what kinds of builds players come up with this time around.

Q: Can we dive into that? What are some examples of two very different builds you guys came up with?

A: My personal favorite is the Devoid set. The idea behind it is that you’ve made a pact with an extraplanar entity, and as part of the deal, it wants to experience sensations. It’s this weird, goofy, oddball concept, but mechanically, it lets you absorb damage into a buff that spreads the damage out over a few seconds instead of taking it all at once. Then, you can use that stored damage with certain abilities to turn it back on your enemies in different ways.

It’s a fun playstyle because you’re walking around with a giant slow hammer, intentionally getting hit on purpose—which feels and weird.

On the complete opposite end of the spectrum, there’s the Slinger set, which is the dedicated ranged build. You craft spears and start chucking them. As you progress, you gain a stat called Drift, which lets you recycle spears as you go. The further you spec into it, the more efficient it becomes, so by the endgame, you’re a spear machine gun—just ramping up and launching them at ridiculous speeds.

And that’s just two of them! There are, I think, six different sets in total, and they all feel really distinct.

Q: What would you say are Crashlands’ design pillars? Is there something that’s particularly important to “get right?”

A: I think a lot of players respond to the humor and the kind of whiplash we provide. We’ve got all this really whimsical stuff going on, and then—every so often—these emotional beats that just punch you in the gut a little bit. We could only do so much with that in the original, both from an art and writing standpoint. We didn’t even have a dedicated writer back then—but we do now. So in

Crashlands 2, the writing is just better across the board. It still has that lighthearted, slapstick nonsense, but now there are these really heavy, emotional moments woven in. Even during Alpha testing, we’ve seen players respond strongly to those shifts.

I think part of the magic is that mix—there’s a whimsicality to it, but there’s an underlying depth that creates contrast. One of our core pillars for the sequel was the idea of being “overflowing with charm.” That’s a big reason we switched to the new 2D animation style and the isometric view—so that everything, even something as basic as Flux running, could evoke some emotional response or just make people laugh.

That goal meant pushing the limits while still keeping things like customizable equipment. In the original game, Flux’s gear had maybe five or six parts—a head, a torso, limbs—and we just spun them around with code. In Crashlands 2, there are 56 individual pieces, all traditionally animated. We had to break it all up so you could mix and match—wear a different pair of gloves, a different pair of pants, and so on. It was super complicated, but seeing how players react makes it feel worth it.

We’ve even had people laugh out loud just from watching Flux walk for the first time. The run animation is meant to be this loping, goofy thing, and I’m really proud of how we’ve infused that sense of charm into everything—whether it’s the writing, the animation, the art, or the overall experience. That’s been a huge pillar for us throughout development.

Q: How would you describe Crashlands’ identity? If there were a Crashlands 4 or 5, is there something that would probably be in all of them?

A: At its core, Crashlands 2 is this blend of humor, discovery, and ecology. You’re on a weird alien planet, scavenging, surviving, constantly wondering, “What the heck is happening?” Then there’s the ecology side—everything interacts, plants and creatures react to each other, and you start to piece together how it all fits.

Something that’s really surfaced in Crashlands 2 is this underlying theme of found family—building a community in a gaming context. A lot of great RPGs have memorable companion characters, and we’ve leaned more into that aspect of RPG design this time around. I imagine that’s something we’ll carry forward into any future games as well.

While we’ve pushed everything further in Crashlands 2, it’s interesting to think about where we could take it next. It’s like a prism—hold it up to the light, and suddenly there are all these different ways we could approach it. There’s no real limit to where we can go with it.

That was part of the challenge of making a sequel—figuring out what resonated with people and ensuring we didn’t mess it up. We didn’t want to remove something only to find out later that it was someone’s favorite part. Early on, we worried that shifting from simple controls to more complex ones might be a problem, that maybe simplicity was part of the game’s core identity. After playtesting, we realized people just wanted more Crashlands—not in the sense of keeping every mechanic the same, but in terms of the experience itself.

In a way, developing this sequel has been a journey of discovery, just like playing the game itself. We built it so fast that, looking back, it’s almost a blur. Through that process, we really came to understand what Crashlands is at its heart. It’s been an interesting ride.

Q: Ecology was a fun part of Crashlands. Can you talk about how the sequel has honed in on that aspect?

A: You’re showing up on an alien world, right? So the question becomes: “What does that actually mean for you as a player?” What’s interesting is that Crashlands is often labeled as a survival game. Genre-wise, that’s how players tag it. In reality, there are no traditional survival elements—no drinking water, no equipment breaking. It’s actually more like an anthropology simulator. You’re constantly encountering weird stuff and trying to make sense of it.

One of the biggest differences in Crashlands 2 is that creatures can fight each other. We toyed with this idea in the original, but it was too messy to manage at the time. Now, it opens up all sorts of possibilities. On the design side, we can make creatures more aggressive because players can manipulate them into fighting each other—just bait them in, let them duke it out, and then collect the spoils afterward.

It goes even deeper. Creatures don’t just fight each other—they interact with resources too. Some might run over and start chewing on things. Take the Sluggabuns, for example—these weird slug-seal creatures you meet at the start of the game. They love biting stuff, and sometimes that means chomping down on an explosive fungus. If they survive the blast but accidentally hit another Sluggabun, suddenly, they’re fighting each other. We built a sort of “blame system,” so if a creature gets hit by another, they assume it was on purpose and retaliate.

1:27

Related

How Three Highly Acclaimed Survival Crafting Games Inspired The Last Plague: Blight

The upcoming survival game, The Last Plague: Blight, offers a unique twist inspired by three titles.

What’s been fascinating to watch is how players interpret all of this. Even though it’s all relatively simple from a code standpoint, players start attributing personalities and motives to creatures. Take the Ampes—little blue electric badger-like creatures. They randomly stand up and look around, but players assume they’re sniffing them out, hunting them. It’s completely emergent gameplay—just a random behavior that makes them feel alive in a way that can be downright terrifying.

Beyond that, creatures interact with resources in more ways. Ampes, for instance, charge up electrified stones, which the player can eventually harvest. You can throw treats to creatures to lure them around. There are all these fun, interwoven ecological behaviors that players can watch, manipulate, and use to their advantage—whether they want to make their lives easier or just create absolute chaos.

Figuring all this out was a nightmare, but once we did, it became one of the most exciting aspects of the game. Every time we introduce a new creature, we ask, “How does this fit into the ecosystem? Does it interact with resources? Does something happen when it dies?” It’s this endless rabbit hole of possibilities, and honestly, that’s part of the fun.

Crashlands 2 Isn’t Quite a Survival Game

Q: You mentioned how people sometimes call Crashlands a survival game, but it doesn’t quite fit that description. Did you ever consider implementing more survival-style mechanics?

A: I’d say the fundamental aspects of survival games have never really interested us—things like weapon durability or strict inventory management. Honestly, we all hate inventory management in basically any game. The only real exception is something like Resident Evil, where it heightens the emotional experience.

None of those traditional survival mechanics made sense for Crashlands. Instead, we pulled inspiration from other places. For example, when Valheim first came out, we played a lot of it. The way you drop all your stuff when you die is obviously annoying, but it also turns recovering your items into its own adventure. That idea stuck with us, and we asked ourselves: “Is there a way we can bring that kind of tension into Crashlands while still keeping its soft, approachable design?”

Internally, we actually refer to Crashlands as a “thrival” game instead of a survival game. It’s not about struggling to stay alive—it’s about showing up and being awesome. You’re not scraping by in space; you’re thriving in it. We never officially called it that because, well, thrival is a weird word to write out, but that’s exactly how we think about it. It’s a game that asks you to build on strengths rather than manage weaknesses.

That said, we do borrow certain survival mechanics in targeted ways to create those moments of tension and excitement. For example, when you die in normal mode, you drop half your inventory. But since Crashlands has infinite inventory, this can lead to some ridiculous situations—if you’ve been playing for two hours and die, you might drop 4,000 items. It’s hilarious, but you can always go back and pick them up.

As you increase the difficulty, this system ramps up, making death feel riskier. Overall, it’s about selectively using survival mechanics in ways that enhance the experience rather than bogging players down with tedious micromanagement.

That appeals to me and likely others who enjoy the progression loop of survival games—chop down trees, build a house, craft better tools—but I don’t want to have to worry about not having enough bag space for this twig.

A: Yeah, we’ve leaned more heavily into the action RPG side of things and then with the fun parts, to me, of what you consider a survival game, which is really about world exploration and harvesting and building a house. Creativity—that’s the juice! That underlies the whole thing.

Q: Earlier you mentioned base building has seen some touch-ups. Can you talk about how things have expanded on that front?

A: The first one just had those knee-high walls. Also, the fact that there was no real purpose for it, right? You just needed a floor to put a station on. That was literally all you needed. We saw players who would just run around and carry a single floor and their station with them, then plop it down and go. There was no real “home” element, so we tried to figure out a way to incentivize base building, even for people like me, who is a notorious “murder hobo” in an RPG sense. How do you get someone like that to take a

minute and build out a space, but in a way that’s enjoyable and not just tedious?

This merged with how we decided to handle the player’s growth process in terms of crafting recipes. In the original game, you only got them from quests, which was because, again, providing reasons was the only control mechanism we had. In Crashlands 2, you get them largely through research done by friends—these alien buddies you make, each with their own stories, kind of like RPG companions. You’ll come across them and realize that they’re people you could essentially get to live with you. By providing them certain amenities, either in their room or throughout the structure of your base, they’ll increase their capabilities, like how quickly they research and unlock new stuff.

Once we tied those together with a comfort system (where it’s not super strict, just “make it big” or “make it nice”), players had the freedom to design things in their own way. We never got reports that it felt like a burden. It ended up being more like, “I’m gonna do it this way as a particular kind of player, and however much energy I want to put into it, I can.”

That was a big thing we were thinking about—how to make base building worthwhile and incentivized, but not onerous for more action-oriented players. I think we managed to thread that needle pretty well. And we have roofs, which, frankly, is a huge technical achievement.

Q: What was your approach to the characters and quests that players will encounter? How has that expanded since the first game?

A: I think a big part of it is the longer arcs you’ll see in a lot of ways. In the original, we had your main quest line and then tons of random oddities, which we still have. Since we didn’t have a system like the buddies (the people who live with you), there weren’t really any longer story arcs. In Crashlands 2, a lot of energy went into the more interesting relationships with those companions, as well as just the main arc. The main story is great, but I can’t say anything about it yet. I’m really excited to see how people experience it. Along with that, we still have plenty of the random, quirky quests that people loved from the original—where you’re just like, “What is happening right now?”

One of the earliest ones is when you walk into the first town, and two people are arguing about how to fold a plant. They’re like, “Do you do it this way, or do you do it this way?” You get a quest to ally with one of them over the other, which involves you slapping or dancing along with the leaves. It’s this weird, four or five-minute thing. Because of all the quest tech we built, we can do quite a few of those where it’s like, “This is odd.” You know the whole time that it’s a unique experience.

That was a big thing we pushed for—how to make authored content at scale, so that you constantly get the sense of, “I haven’t seen this done yet in this game.” We do that throughout, rather than an individual connection that kind of peters out after the first zone. In Crashlands 2, there’s just random new stuff happening all the time. It’s been a big achievement on our part, both from a technical and scale perspective.

Q: I know you can’t reveal too much about the main arc, but can you talk about what kind of story you wanted to tell in Crashlands 2?

A: I think a big part of it was that we started in December of 2020, and a lot of it was about finding a way to revisit the original thematic arc. The first game was about being thrown into a rough situation and just trying to do your best to get your job done. There was a lot of corporate nonsense baked into that theme.

With Crashlands 2, we wanted to move away from the idea of strength only coming from being alone and instead push more into themes of connection and community—the power that comes from actually knowing your neighbors and spending time with them. Some of the core themes remain the same, like making fun of corporate bureaucracy and capitalism, but the way we express them is different. You’re still a powerful hero in this story, but you’re also relying on and building friendships with people who have their own stakes in this predicament.

We always gravitate toward bureaucracy as a comedic element, but ultimately, the story we want to tell isn’t just about the player being a hero. It’s about becoming more connected, or even becoming more whole through the process. Anyone can fight a battle and come out wounded for life, but can you go through something deeply challenging and actually come out with more—more friendships, more strength, more understanding of yourself?

As someone who has been through cancer treatment and survival, that idea of post-traumatic growth is just naturally embedded in what we do. It’s not just about surviving. It’s about coming out the other side changed, realizing new things about yourself, and becoming more of who you are than you were before. I think we try to get that in there, and in every which way it comes out.

That’s a refreshing perspective. A lot of games seem to put the protagonist through the wringer and leave them broken. In my experience, you can come out of hardships better, not worse.

A: 100%. Challenge is a way of reforging yourself, and so we try to bring that in. That’s the whole idea of the thriving aspect, instead of just surviving.

Q: Earlier we talked a bit about some action RPG influences in Crashlands. Can you talk about how that inspired your approach to loot and gear?

A: I think a lot of that came down to changing the overarching control to allow for more complexity in the combat and to get more out of what we were trying to do in the first place. One key addition was the dodge mechanic, which made the combat a lot more interesting. On top of that, players need to commit to actions. This was inspired by games like Elden Ring or Dark Souls.

There’s something about that kind of combat that resonated with Crashlands 2, especially the idea of being planted for a moment.

It’s not just about avoiding the red stuff or staying out of the circles; you have to time your actions just right. It really ups the stakes. Once we had some of these basic layers of combat figured out, we started thinking about what equipment really means in the context of the game. In the original game, one of the big issues was that the loop exposed itself early on: you hit a new station, build the same armor or weapon, just slightly better. You could add random rolls, which were fun, but it was essentially us trying to patch over the fact that we couldn’t design a more coherent system.

In Crashlands 2, we focused on making the equipment more bespoke and long-lasting. Weapons last longer before you need to upgrade, and each weapon feels unique. If you want to change your playstyle, the different weapons really feel different. Gadgets and trinkets are still a big part of it, but each one offers a unique way to play the game. As you build out your kit, it really feels personal. To me, that’s what makes action RPGs fun—like when you’re playing Diablo 4, getting loot is great, but what really makes it exciting is getting the right synergy with your build. That’s why you do the loot runs.

We decided to stop worrying so much about randomizing everything. In Crashlands 2, we don’t randomize gear. Instead, we focused on making the build system super satisfying, and it turned out that worked really well. We didn’t need to add randomization, which was a nice surprise.

Related

10 Easy Survival Games

For players who want to enjoy the survival genre without facing too many tough challenges, the following ten games are well worth considering.

Q: You mentioned re-speccing. Is there a rigid class system where you choose a class, or is that determined by the gear you equip?

A: It’s all equipment-based. The big advantage here is the flexibility—it makes every piece of equipment feel interesting. Even if I’m playing the same way every time, whenever I discover a new trinket or gadget out in the world, I’m thinking, “Maybe I should try those knuckles finally.” That’s the goal: to make every piece of equipment intriguing enough that players want to swap it out whenever they find something new, or even integrate it into their build for a while to see how fun it is.

I love class systems and that kind of structure, but what’s great about this looser approach, where everything’s based on equipment, is the flexibility it offers. It makes every crafted item important—you’ll want to find and collect all of them, just in case there’s something cool you’re missing. And if you ever decide to change up your playstyle, it’s as simple as swapping out your gear and adjusting it into your rotation. That’s been a lot of fun for us.

Designing Crashlands 2’s Unique Creatures

Q: Back to Crashlands 2’s ecology, do you have a favorite creature or one that particularly sticks out to you?

A: One of the most fun parts of working on this has been expanding on the creatures. In the original, most creatures only had one attack, and maybe a second one if they were a bigger version—like a larger wompit. It was pretty basic. But with Crashlands 2, we’ve expanded that. There are adult versions, standard versions, and little baby ones running around. We’ve added complexity to the combat by giving the bigger versions unique moves.

One of my favorites, in terms of how weird it is, is in the second zone of the game, which has this desert, spooky vibe. There are these creatures called “shmoos,” which are like hammerhead tree frog bats. The cool part is that when a shmoo’s health gets low, it splits into more shmoos! It’s one of those weird, unsettling moments when you first fight one, and you’re like, “What is happening?” It’s terrifying but also a lot of fun.

We’ve made sure that each creature is unique in its own weird way, and the goal is that, for any player, there’s at least one creature that’s like, “This is my ride-or-die pet!”

Q: How do you even come up with a shmoo? What’s the process like leading up to “here’s a hammerhead tree frog bat and also it’s called a shmoo.”

A: I think a lot of it comes down to looking at the context the player is going to be in. At the start of the game, we think, “Okay, we want to introduce the player to these creatures. What do we need?” We start with something that’s squishy, something that feels like it won’t murder you instantly. So we begin there and then look for more animals that are squishy or weird—something that isn’t super tropey but still fits the tone of the game. We also want to make sure it’s not something that players will instantly hate. It can’t be too hideous, or players will just despise it, so it needs to be approachable.

Once we hone in on the concept, we disappear for a bit, come back with sketches, and go from there. It’s all about context. For example, with the schmooze, we knew that once players reach the middle of the game, they might think they’ve seen it all—creatures that spit things at them, creatures that charge and bite, creatures that shoot acid. So we wanted to zag instead of following the obvious path. We asked, “How do we surprise the player?” and then came up with something weird like the shmoos.

That’s 90% of it—figuring out how to keep the player engaged and thinking, “I haven’t seen this before.”

I see, so it’s bottom-up design where you’re building around a situation you want to create for the player.

A: Yeah, and what’s so weird about this is that to make a game like this, it’s a tremendous integration challenge. We’re not just making a weapon. We’re making a weapon out of parts from creatures that live in this specific context and eat certain things.

Before we can even create equipment for a given tier of content, we first have to design the land, create the resources there, make the creatures that interact with those resources, and then figure out all the drops that come from those creatures. We have to think about how everything fits together, and it’s a lot more complicated than it sounds.

We had to create all sorts of additional tooling this time around because the system became so intricate. It was essential to map how all of this content flows and understand how the player might experience it. This helped us decide what equipment should be available at certain times. It’s a complex puzzle, trying to pull everything together cohesively.

Q: There’s been a dramatic improvement in the visuals along with a perspective change. What was your approach to Crashlands 2 on the visual side?

A: I do the art for games, and I’ve been doing it since the beginning. After our last game, Levelhead, launched in April 2020, it was a weird situation. The players who played it loved it, and the game was successful from a business standpoint. We made back our money and had enough deals to be fine, but it didn’t really take off on its own. A lot of the comments I’d heard during development, especially from businesses and platforms, were about the art, and they weren’t meant to be patronizing, but they sort of came off that way. They’d say things like, “Oh, this is kind of retro-looking.” It wasn’t that they meant anything negative by it, but it made me realize that we weren’t being fully recognized for what we were trying to do.

After Levelhead launched, I went through a phase of frustration for about six or eight months. During that time, while we were working on post-launch content for Levelhead, I also began to build up new skills. I switched from using vector tools and Inkscape to Clip Studio Paint and Spine. I started learning animation because I hadn’t done much of it before. It was driven by an anger at not being fully seen. I didn’t want to be ignored when we released a game. I didn’t want people to dismiss it based on how it looked. I wanted people to be grabbed by it, to feel like they wanted to know more just by looking at it. I didn’t want to have to explain why it was good.

A big part of that realization was understanding that I didn’t have all the skills yet to get where I wanted to go, so I pushed myself to improve. The switch to an isometric view was part of that shift. It made the world look so much more interesting than just a flat, grid-based approach. We also pushed the scale of things in the world; the original game only had things that were one grid space in size. Now, we could have things five tiles wide and five tiles tall, which helped make the world feel more dynamic. But this meant we had to be really careful about how things loaded on screen so they didn’t pop in at the wrong time.

A lot of the early development was about making sure the game looked good because no matter how good the gameplay was if people didn’t immediately want to dive into the world when they saw it, it wouldn’t matter. We spent a lot of time perfecting the water, making sure the layers of tiles and gradients all came together seamlessly. It was a long process, but it came from a place of frustration and the desire to make the world feel just right.

Q: Was there also a lot of focus on the sound and music this time around?

A: Oh, 100%. Before we started this project, I did a big review of all the reviews for the original Crashlands. I called it my “reviews review,” where I looked at not just player sentiment, but also critical reviews from the press. I was trying to understand what stood out to people, what the problems were, and what we had even made in the first place. From there, we could figure out how to take what we made and build something better.

One thing that came up repeatedly in the reviews was that, because Crashlands was a crafting game and more of an open-world survival game, people could easily spend 40 hours in the game. The number of music tracks in the original was too low. People liked the music that was there, but it was basically just one track per zone, which got repetitive. So, for the new game, we started working with Fat Bard, the same team that did the sound for Crashlands. We brought them in right from the start and had them working on new music constantly.

Now, we have different music for day and night, NPC-specific themes, music for some of the buddies, themes for certain species and their towns, and even indoor music. The acoustics are now 1000 times richer than the first game. We also built some new tech tools to make things even more interesting. For example, you’ll hear animal sounds fade out in certain ways, and there’s this one creature—these huge, manta-ray-like things called Fantas—that make owl-like hoots at night.

There are all sorts of details like that to bring the alien wilderness to life. We wanted to capture the feeling of hearing spooky sounds in the distance at night, where you can’t see what’s making the noise, but you know it’s out there. We spent a lot of time figuring out how to technically make those things happen.

We wanted the new game to feel like a natural evolution of Crashlands. When players sit down to play it, they should feel like it’s a massive upgrade. We had people in the alpha test comment on how it felt like we’d taken the original game and just cranked everything up to the max.

Q: Is there anything we haven’t covered that you’d like to mention?

A: I think we’ve covered most of it. One question we get asked a lot is, “What did you decide not to include?” We’ve mentioned a few things, but I think, overall, we didn’t bring a lot of specific elements from the first game over. As far as that high-level, remembered experience of the first Crashlands, I really feel like we’ve managed to bring all of that forward in a way that, hopefully, meets everyone’s expectations.

That’s a big part of making a sequel right—making sure you don’t just change things randomly for the sake of it. There have been games recently where you see the name, but when you play it, it doesn’t feel like it’s quite hitting the mark. We really wanted to thread that needle: build something new while still meeting player expectations and elevating the experience across the board. My hope is that when this game comes out in a couple of months, everyone will be able to look at it and say, “Yes!”—and then maybe I can take a nap.

Q: Any final thoughts you’d like to share?

A: On a personal note, this has been a very transformational game to work on. I pitched it back in July of 2020, and afterward, Seth—one of our game programmers—looked at me and said, “You know, we can’t actually build this, right?” I was like, “But what if we could? And what would that look like?”

The first two years were literally about figuring out how to make ourselves into a studio that could build Crashlands 2. We’re talking retooling everything from top to bottom, including our production process and, on a personal level, even the art. During all of this, something incredible happened: no one in the studio was a parent at the start, and now, half of us are, with four babies born during development. It’s insane!

It’s been such a transformational four-and-a-half years, and I really hope that the vision we had for this game and what it can bring to people lands the way we want it to. It’s fun for us to make these things, of course, but what’s really exciting is seeing it resonate with people at the end of the day, in the same ways that it resonated with us during development. It’s been a refuge for us through all the trials of life, and I hope everyone who plays it gets to experience some of that, too.

[END]

Crashlands 2 is set to release on April 10 on PC.

Action-Adventure

Survival

- Released

-

January 21, 2016

- ESRB

-

T For Teen: Blood, Violence

- Developer(s)

-

Butterscotch Shenanigans

- Publisher(s)

-

Butterscotch Shenanigans

Source link

Leave a Reply