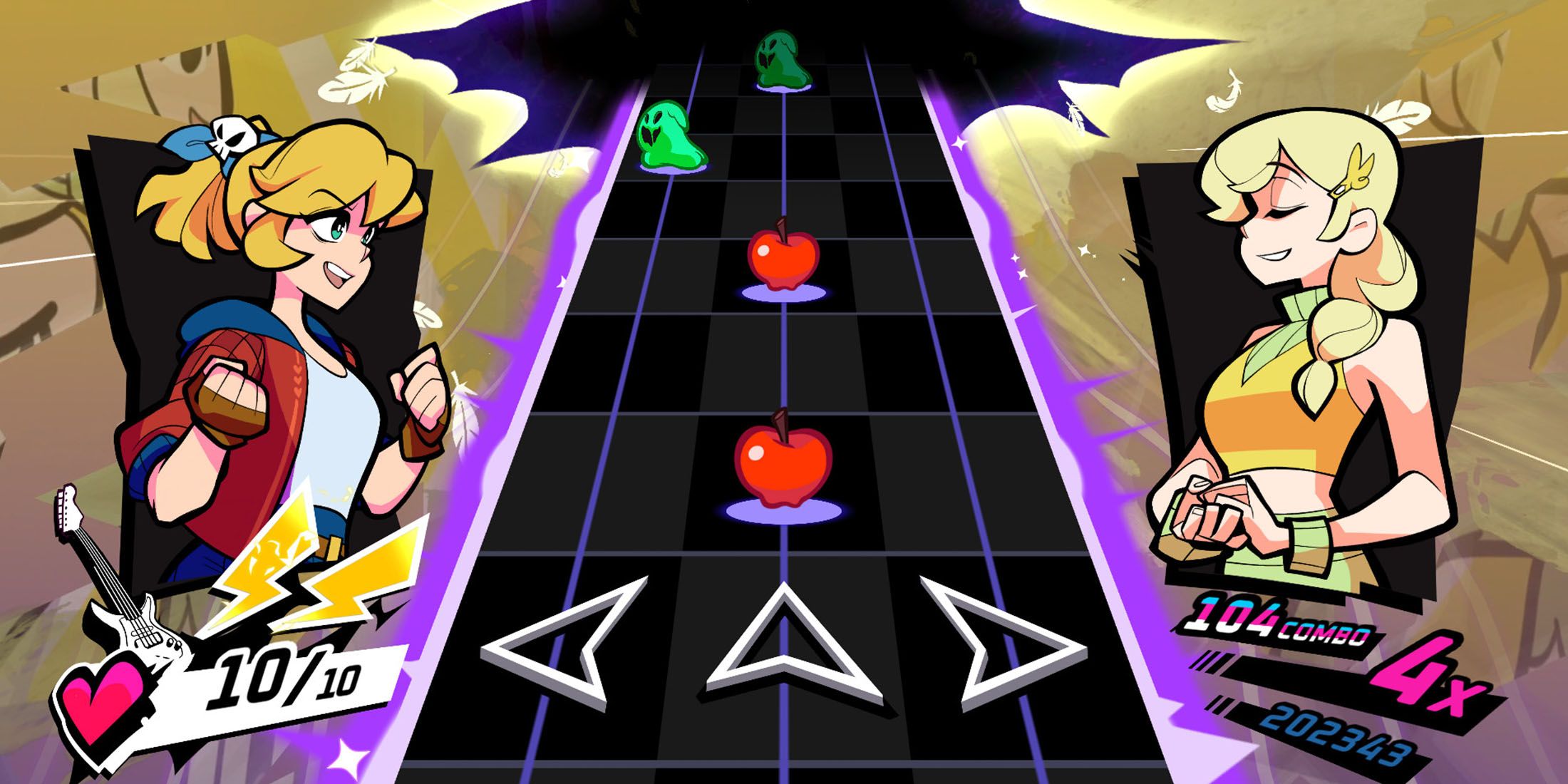

Rift of the NecroDancer is a follow-up to Brace Yourself Games’ hit roguelike dungeon crawling rhythm game Crypt of the NecroDancer, this time leaning into the more traditional chart-based rhythm game structure popularized by the likes of Guitar Hero. That said, Rift of the NecroDancer is no ordinary rhythm game: rather than players merely reading a chart and playing notes accordingly, the track is populated with monsters with unique behaviors that react to the player’s inputs. This clever twist turns rhythm gaming on its head, as players must play to the beat while reacting to how upcoming monsters will behave. With this one departure from genre norms, Rift of the NecroDancer is a rhythm indie game that plays like no other.

In an interview with Game Rant, Rift of the NecroDancer game design director Aaron Gordon and legendary composer Danny Baranowski (DannyB) spoke about the game’s inspired take on the rhythm game formula. They discussed their approach to the game’s array of monsters inspired by Crypt of the NecroDancer and how this influenced chart design, and they also weighed in on how a rhythm game benefits from music that’s designed specifically for it, as opposed to most rhythm games that build charts around existing music. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Related

5 Best Rhythm Games For Beginners

Players new to the rhythm genre can begin their journey with these games.

Rift of the NecroDancer’s Unique Monster-Based Track Design

Q: Rift of the NecroDancer uses a Guitar Hero-like format this time as opposed to the dungeon crawler approach of Crypt. What inspired this gameplay style, and what are its benefits?

Gordon: Some people say that Crypt of the NecroDancer isn’t really a rhythm game because you’re constantly moving to the beat, unlike other rhythm games where there’s more variability in when players act and what they do. However, we feel strongly that Crypt is a rhythm game with a lot of optionality and strategy that other rhythm games don’t necessarily have.

Most other rhythm games tend to be more like Simon Says, right? You do the thing you’re told. Crypt allowed players to react how they wanted, to plan and strategize. It’s more emotionally focused. Many other rhythm games focus purely on accuracy and less on strategy. It’s less about perfect execution and more about giving you options and freedom.

Rift of the NecroDancer was our attempt to create a hybrid between a pure rhythm game and Crypt of the NecroDancer. Since monsters in Rift react when they’re attacked, you’ve got to process a lot more information and plan. The goal was to get the best of both worlds—something that looks familiar, like a traditional rhythm game, but with added mechanics, like monsters that behave differently when you hit them.

Q: What were some of your design pillars for Rift? When planning the game, were there things you felt were important to include?

Gordon: Our three main pillars throughout production have been:

Our Delightful Crypt IP – We think fans want to see more characters from Crypt of the NecroDancer, and we want to give that to them. We want to tell a story that supports the gameplay and meets the expectations of existing fans. Crypt fans come into the game expecting a certain level of difficulty and a high degree of musical fidelity and quality. We’re committed to delivering that.

Rhythm-Action Excellence – Gameplay that supports the music is key, just like in Crypt. Everything happens on the beat, and the music is very beat-focused. We want to ensure that all our charting and gameplay highlight the music. That’s one of the things that makes this game awesome. At the same time, the music also elevates the gameplay. It’s a hand-in-hand process. For example, DannyB might make a track, and we’ll start jamming with it and realize, “Oh, this allows us to do something new!” Maybe we use a specific pattern of monsters or design a new one to match a musical motif and leverage the track.

Since it’s a rhythm game, readability and reliability are also crucial. When you hit a note, you need to know you hit it. If you miss something, it should be clear to the player: “I missed that, it’s my bad, but I can practice and improve.”

Innovation – Innovation has always been a staple of the NecroDancer IP. Crypt of the NecroDancer was very innovative in its gameplay, and we want Rift of the NecroDancer to follow that tradition. That’s where monsters behaving differently when you hit them comes in.

Finally, long-term replayability is essential. Crypt is a game people come back to again and again, and we want Rift to have that same appeal. We’re aiming for a new, exciting way to play that isn’t just a gimmick but something you’ll want to stick with. We plan to support the game long-term with new monsters, tracks, and high-quality content.

We also want to lower the barrier to entry. So, we’re including features like an easy mode and assist modes with more on-screen indicators and additional help. These options allow more players to enjoy the game while still maintaining the high skill ceiling that Crypt fans expect.

Q: We may have touched on this in your answer, but how would you describe NecroDancer’s identity? Is there a common thread that should be present in NecroDancer games? Something that embodies the IP for you?

Gordon: It’s definitely puns. As soon as someone explained that one of the main characters in Crypt was Coda, I was like, “Oh yeah, Coda.” And then a year later, it hit me: “Wait a second, that’s a musical term. Wait a second… Melody, Harmony, Cadence… wait a second!” Everywhere I looked in Crypt, it was chock full to the brim with puns. Then I go back to our story mode and see that every chapter is a play on musical lyrics. My favorite one is The Audacity of this Lich. That’s when you meet the NecroDancer for the first time.

In terms of gameplay, seriously—NecroDancer and Cadence are staples and core to the franchise, as is innovation. With any NecroDancer game we make, we always want to find unique ways to explore the rhythm genre, to do things that haven’t been done before, things we want to exist in the world, and to give fans those new experiences as well.

Q: Monsters can move around the track in Rift of the NecroDancer. Do you feel this unique behavior changes how you approach creating charts compared to a typical rhythm game?

Gordon: This has been the most fun part of the game, and it’s also the thing we’ve spent the most time and dedication on because it’s what makes the entire game musical. Accuracy is so important to us. Each track has gone through countless rounds of iteration, from level designers up to DannyB, who helps us nail tricky musical motifs.

Our main focus is to make each chart feel like the player is playing along with the music. That’s the one thing we always ask: “Does it feel like you’re playing along to the music?” We also make sure the monster placement is musically accurate. For example, when you hit something, you should hear that it matches the lead guitar if the monsters follow that instrument. And if we want to switch to a different instrument, we make it a big, dramatic moment. We might even introduce a new monster to show that this one is now following the drums, while the other is still following the guitar.

We like to think of the music as the terrain of the game. It’s the foundation where level designers come in and create gameplay experiences. We aim to leverage the strengths of the terrain and elevate what’s already there. The process usually starts with us listening to a track. We identify what stands out—whether it’s specific instruments, the vibe, the intensity, or the meter. For example, if it’s in triplets or has heavy hits, we ask, “Which monsters best highlight those elements?”

In some tracks, we might say, “Okay, this one is bouncy and light,” so we’ll choose multi-hit enemies that stay on the Rift longer, making it feel like they’re bouncing along with the music. You really feel it in your body when you play the game. We also strive to make each level’s gameplay style unique. Each chart focuses on a specific set of monsters, a pattern, or a musical motif.

In story mode, we introduce a new monster with each storyline track and make it the star. For example, one level might be NecroDancer-themed with lots of skeletons and skulls, while a Suzu level later in the game is heavy on blade masters because that’s where the monster is introduced. We don’t want to overwhelm the player with too much at once, so we focus on a smaller subset of monsters that best highlight the track’s features.

We also go through rigorous playtesting with the team and work closely with DannyB to fine-tune the vibe and accuracy of tricky musical arrangements. Sometimes, Danny will suggest tweaks like adding a rest before a big hit to make the impact stronger. We’ve found that even non-musical players can feel the difference—it becomes more intuitive on a subconscious level.

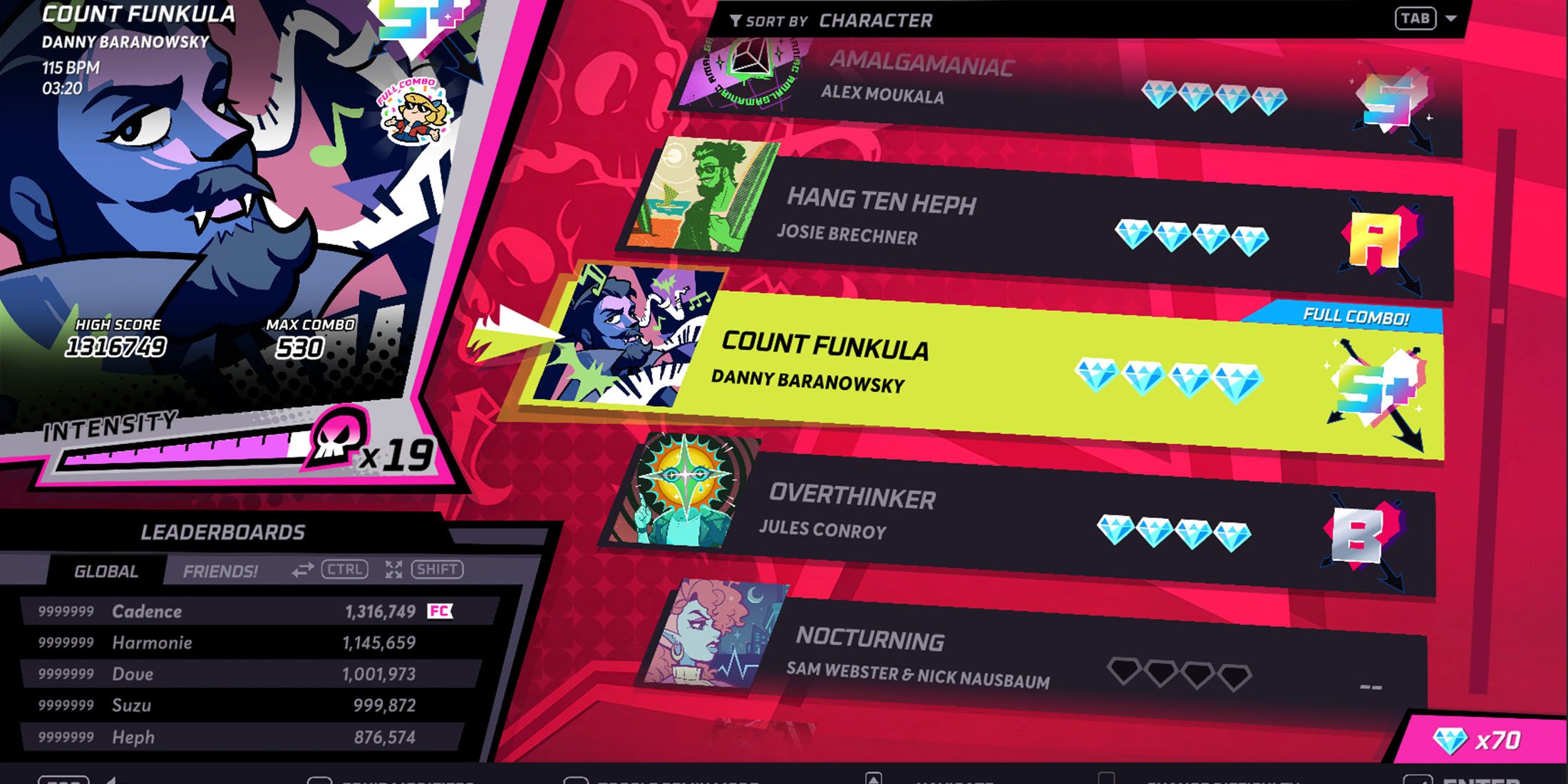

We’ve gotten incredible feedback from external playtesters too. We have a dedicated group of fans who are self-proclaimed rhythm gamers. Honestly, we’re a bit afraid of them. We’ll send them something on our hardest difficulty—what we call Impossible Mode—and they’ll S+ rank it and full-combo it within minutes. Only one person at our studio can do that, so we’re left wondering, “How can they do that? How do they blast through our high scores so easily?”

As a musician myself, I enjoyed the musicality of Rift of the NecroDancer. I was thrilled to see that there’s even a monster that’s a triplet without the middle note.

Gordon: That’s a great example of how we both up each other’s game. Level design will come to Danny, and we’ll have a jam session where we’re like, “We’re struggling to nail this one part.” Sometimes we can’t fully figure out the issue in the moment, but it just takes one listen, and Danny will say something like, “You’re trying to use a shielded skeleton, but its mechanics only work in duple meter tracks. This section is in triplets, so it’s never going to land the way you want. You’ll need something else.”

Then we’ll realize, “We need a new monster.” And Danny will add, “Not only do you need a monster for triplets, but if it’s swung triplets, you’ll need a variation for that too. And while you’re at it, why not create one for this other pattern as well?”

We go back to the design team and create a new monster that allows us to hit those notes accurately where it wasn’t working before. Then we’ll do another pass through all of our tracks, and suddenly, it clicks. That’s what was missing from the song—it wasn’t fully musically accurate until we added that new element.

Q: What was the approach to Rift’s music this time around? Were there new musical ideas you wanted to explore or different ways to tie them to gameplay?

Baranowski: The goals for the music were different from Crypt and Cadence of Hyrule in that those games were locked to the beat. The rhythm had no subdivisions; the player was simply tasked with making one move per beat. The gameplay’s appeal resided in the broader, “tactical” approach to the threats on-screen. All the player needed to do was make one input per beat while being aware of the threats coming their way and reading the board to ensure proper positioning to survive and eliminate enemies.

Because of those gameplay considerations, the music in the previous games focused primarily on having an eminently “readable” beat. In some cases, heavily syncopated (roughly speaking, off-beat and potentially complicated rhythms) had to be simplified sometimes, as players would have to divert too much attention to finding the pulse and that detracted from the core appeal of the game – making interesting decisions on every beat. The puzzle of the gameplay was king, and the music needed to serve that goal to be successful.

In some of Rift’s game modes, particularly minigames, this restriction still mostly applies. In Rift’s main gameplay mode, the Rhythm Rifts, the consideration of “one move per beat” doesn’t exist, and the design goals of the music change as a result. This removes a restriction on the music design – more complicated rhythms and patterns are possible, and even called for. The challenge then becomes what to do with this increased freedom. Rift hews more closely to games like Guitar Hero and Amplitude where levels are designed around a music track, meaning that the level design necessarily hinges on the composition and arrangement of the track.

Our approach to this was straightforward. The tracks needed to be levels. As opposed to many of our rhythm game forebears, we were writing music from scratch specifically for the game. Whereas in many rhythm games, the design challenge is to create a level map on top of an existing song that was never intended to be a video game level, we could approach the composition with that foreknowledge. We could think “Would this be fun to play?” and “Would this get rhythm or section get annoying to play over and over again?” I generally prefer to through-compose (simply: very few elements or sections in a song repeat, my go-to example is Paranoid Android by Radiohead) when I write, which helps to give the levels a sense of progression.

Potentially, a level with a common verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-ending format could feel repetitive. If there was no repetition at all, it could feel scattershot or haphazard. So we tried to ride that line between through-composed and a more conventional arrangement style, and I’m really happy with how the other composers approached this.

The spread of musical perspectives the team brought to the soundtrack all appropriately rode that line. Sam and Nick’s tracks seem deceptively simple until you start appreciating the subtle variations that occur in repeating sections. Jules’ and Alex’s tracks seem to more closely follow traditional song structures, until BAM – they don’t. Josie is particularly adept in through-composition, her tracks pivot and morph and change in ways you never expect, but still feel cohesive.

Hopefully, this varied collective of approaches to arrangement allows for an experience that feels learnable and approachable, but surprising and challenging. And with the nature of the Rhythm Rifts as they are, where you’re fighting off this cavalcade of musical monsters, if the result is that players feel like they’re occasionally able to “see things before they happen,” perhaps without fully understanding why, then our approach will have been a success.

Q: When coming up with music for Necrodancer, what do you tend to look for in composition, songwriting, or sound design? Are there certain genres you feel work better or worse in a game like this?

Baranowski: Much of the aesthetic approach for NecroDancer’s music follows from a snap judgment made at the moment, many years ago, that has persisted and grown and evolved. When I first started writing NecroDancer music, I wasn’t armed with much more than a simple concept – “make dance music for a medieval dungeon represented by pixel art.” This is often all you get in my line of work. Games are often in prototype stages if you’re fortunate enough to be brought on early, and you have to see past the jank and try to make the best artistic decision you can with limited information.

I cranked out the initial version of Disco Descent, the first level of Crypt of the NecroDancer, in like an hour or two. It was a simple melody where I was trying to hit fantasy, spooky, dancey, and retro all in one. That single session turned out to be pretty damn consequential for my musical career; I feel as though all of the NecroDancer music I’ve written since then descended from that original track. I’m personally interested in putting music genres where they aren’t supposed to be. In Crypt of the NecroDancer, I tried to sprawl out as much as I could. I tried to write EDM, reggae, trap, funk, drum ‘n’ bass – you name it. My accuracy rating on hitting those genres was wildly inconsistent, but I was still happy. I might not be able to nail the intricacies of drum ‘n’ bass production, but honestly? I don’t care. It’s fun to try, miss the mark, and end up somewhere you didn’t expect.

I’ve always subscribed to “if it sounds good, it is good.” I operate on instinct, vibes, and diet cola and only bring in the music theory and genre considerations when I feel something has gone too far off the rails. I used to consider this a weakness. I used to listen to the NecroDancer stuff and think “Why can’t I make an EDM club track hit like they do in the club?” but people seemed to respond to it. More importantly, I started to respond to it.

I think that high-end world-class Pop and EDM production is a beautiful thing. Even if I don’t like the music itself, hearing production where every single frequency is in the exact right spot, and every compressor and saturator is precisely dialed in – it’s a thing of beauty, but it’s not me. I’ve come a long way in my production, but I don’t think I ever will or even want to be the cleanest and tightest producer. I find joy and interest in the mistakes, roughness, and fuzzy edges. I approach composition similarly. I have enough of a music theory background to know the simpler things, key signatures, chord modulations, inversions, voicings, etc, but sometimes I’ll write a chord in Cubase and it tells me it’s a D#7b9&e^24 chord, and I’m like, “Sure. Why not?” I’m comfortable with never fully understanding that sh*t.

Aggressively tangential soliloquy aside, all of this explains my approach to writing music for NecroDancer. I have some pillars in my mind. Spooky? For sure. Dancey? Hell yea. Retro? Less so these days, especially for Rift which has a slick and hi-fi presentation, but it’s always on the table. Then I attack it.

Related

8 Best Music Games On Nintendo Switch

The Nintendo Switch had its fair share of great music games. Here’s a look at some of the best.

I start writing until I find that first thing that makes me feel something. I’m not even really concerned with what it makes me feel, at first. If it elicits an emotional response, cool. Then, the rest of the track coalesces around that core. I just need to make it bop so people can nod their heads to it or dance if they want to. Then, there’s got to be some form of spooky, or unsettling, or something in that zone. Again, precision isn’t the most important thing. If I enforced a spooky quotient on every track, everything I wrote would start to sound the same. I embrace the misses and explore where they lead me.

As far as genres being better or worse for these games – I hope not. As long as you’re not trying to chart some Brian Eno or John Cage, I like to think anything can work. It might need to be treated so the rhythm comes to the forefront, but leaving anything off the table seems like a shame. I’ve started playing the NecroDancer music live with my band, dannyBstyle, and one of my favorite tracks to play is Count Funkula. It’s a funky, brassy track that has a solid rhythm, but I don’t remember funk being on the top genres of Guitar Hero. But it’s super fun to play.

That’s been another development over the last year or two – now that I’m playing the drums on these tracks, live, it’s gotten me reacquainted with feeling these things out. Playing the drums on these tracks is probably the closest instrumental equivalent to playing the game itself. That has made my instincts stronger as I wrote tracks later on in development. Rekindling my chops on the drums made it a lot more natural for me to suss out quickly if something would be fun to play in the game.

Q: Were there any monsters that behaved in interesting ways that you needed to scrap for some reason?

Gordon: Yeah, there’s quite a lot we brainstormed and prototyped that didn’t make it into the game, though there aren’t many we put in the game and then took out. We’d love to explore some of those ideas more in the future. We’d often go back to play Crypt of the NecroDancer, and think, “What monster do we want to take from Crypt and give new life?”

For example, we had the Hellhound for a while, which moved diagonally and downward. We also had the Elemental, which would freeze enemies, and those frozen enemies would behave differently depending on whether they were frozen. We also had the Leprechaun and the Pixie, which would do tricky stuff like changing the orientation of monsters. I think the Leprechaun would even transform certain monsters into other monsters.

There was one monster we did take out of the game—a variant of the Blade Master. The Blade Masters usually do a “shing” before attacking you, but this variant could attack you from any row and bounce between all the different rows. It was really cool, but we realized it took up too much space on the Rift since it always needed a clear line of sight to the player. That made things a bit cluttered, and we want every monster to be easily readable.

So, we ended up folding that functionality into another Blade Master. I think that’s the only one I know where we put it in and then took it out, just because we realized we could achieve the same functionality by using the existing Blade Master more smartly.

Q: Were there any lessons learned or player feedback from Crypt of the NecroDancer that you applied this time around?

Gordon: One of the big influences for the project, and something we learned from Crypt, was that fans love our characters. Crypt has been out for a long time and still has a steady following. From that, we learned how much our fans care about the characters and how much they want to spend more time with them.

We also noticed that people loved it whenever we placed our characters in modern clothing in our social media posts. That got us thinking—a game with a bit more character development, set in a modern setting, would make fans happy. It’s also something we wanted to do at the studio.

One of the main things I’ve personally learned is that rhythm gamers are a different breed. They’re crazy dedicated, so passionate about rhythm games, and they get scores that are just off the charts. Whenever I’ve hesitated, thinking, “This might be too hard,” they’re like, “No, give it to me. I can do it. I want to hit my head against the hardest track in the game over and over again.

Q: Can you talk about Rift of the NecroDancer’s story mode? How does that differ from the playlist experience in the demo?

Gordon: The main story follows Cadence after she’s already been in the modern world for a while. She starts noticing monsters coming through the Rift and has to do musical battles with them in what we’re calling Rhythm Rifts, which is the main gameplay you’ve probably seen in the demo. Along the way, you’ll meet some old friends and enemies, make some new ones from the Crypt world, and work together to uncover the mystery of the Rift.

Story Mode takes you through all the main content of the game. You’ll play Rhythm Rifts, experience story dialogue, enjoy mini-games, and fight bosses, all as part of the Story Mode.

Rift of the NecroDancer’s Boss Fights, Mini-Games, and Challenge Modes

Q: Can you talk about the boss fights in Rift? How do they differ mechanically from the other tracks?

Gordon: Each fight pits Cadence against a boss in a one-on-one rhythm duel. Both Cadence and the boss move along to the beat, and the player needs to dodge incoming attacks, stun the boss, and then go in for a counterattack. Each boss introduces a new, unique mechanic that elevates each music track.

For example, the first boss, Harmony, focuses on teaching the player the importance of recognizing the tells of each boss and knowing where to dodge next before doing a counterattack. The rhythm mostly stays on beat to emphasize the music.

Another boss, Deep Blue, is set to a swung triplet track, challenging the player to dodge in time with swung notes and triplets. The player also has to recognize chess pieces flying towards them and react quickly. For example, they might see a rook moving towards them. It moves twice and then attacks diagonally, so they’ll need to dodge to the left before going for a counterattack.

We’ve also added ways to make this easier or harder for players depending on their preference. Players can opt for easier patterns and on-screen indicators if they don’t want to rely on just the animations. For instance, they’ll see a receding circle to guide them, indicating when to dodge left, dodge right, and when to go for the attack. Alternatively, if players want harder patterns that test their ability to react and rely purely on the animations without those on-screen indicators, they can choose that too.

Q: Are the boss fights something you can choose in a playlist whenever you feel like doing them?

Gordon: Yeah, totally. Story Mode will take you through all the content, but we wanted to ensure you get rewarded for everything you do in the game, and that you’ll continue unlocking content quickly. The only reason we gate content is to avoid overwhelming you right at the start with too many things to do.

From the get-go, our main progression system is Diamonds. Every time you play a track, mini-game, or boss fight, you’ll earn Diamonds and immediately start unlocking more and more content. We’ve balanced the game so that if you play everything in easy mode, you’ll unlock all the content. So, we don’t skill-gate a bunch of stuff.

For boss fights specifically, you can either play them as part of the Story Mode, or they start unlocking at increments like 10, 15, or 20 Diamonds. So, even if Story Mode isn’t your thing and you just want to jump straight into it and play through Rhythm Riffs, you’ll unlock a mini-game. Then, after playing the mini-game, you’ll unlock a boss fight.

Q: Earlier we talked about replayability being an important factor in NecroDancer, and it looks like Remix Mode and Daily Challenges are Rift’s answer to that. Can you talk about how these modes shake up gameplay and keep players engaged?

Gordon: Remix Mode takes our existing charts and remixes the monsters and their placements to give the player a brand new chart to play each time. It’ll still feel like you’re playing to the music, so it won’t feel random. For example, whereas before, there may have been one slime on the left and one on the right, now you might hit a skull on the left, which bursts into two skeletons. Then it might turn into a two-hit combo to hit both left and right next.

You can’t just memorize and practice the track—it’s leveraging much more of your understanding of how the Rift mechanics work and how the monsters interact with each other. If a zombie is coming down the track, you’ll need to quickly process that it’s going to hit a slime and end up on the right, when it would normally end up on the left. You need to think and react quickly.

Remix Mode also means if you love a track, you can keep playing it and get a different gameplay experience each time. We also allow you to enter a custom seed. If you want to go seed hunting and find something that gives you the best chance of getting on the leaderboard, you can do that too.

Daily Challenge Mode is really exciting for us—it’s something we haven’t seen in a rhythm game before. Remix Mode unlocks our ability to do this. We have a custom seed shared for everybody, and you get to pick your difficulty: easy, medium, hard, or impossible mode. You get one chance to play the track—no retries, no practice mode. See how high you can get on the leaderboard and then return the next day to do it again.

It’s been really exciting already because as soon as the feature came online, we started playing it on the dev team, and we’ve got some fierce rivalries going on. It’s been fun trying to outdo each other every day.

It sounds like these features are testing players’ knowledge of the mechanics and the music, rather than their memorization of the charts. That’s a great way to draw emphasis on the music and keep it replayable.

Gordon: If you know the track, if you’ve been playing it a lot, if you follow your instincts and understand how the music goes, you can often get through some pretty tricky situations. The focus is so much on musical accuracy that if you trust the rhythm, you’ll find yourself naturally keeping up.

I’ve often played and thought, “Oh, five armadillos are coming at me. I can’t keep up mentally,” but my body still stays in time with the music. And then, somehow, I just go with it—and it works. It’s amazing! We’ve gotten a lot of feedback from players saying the same thing.

Q: You also mentioned mini-games. How do the mini-games play out? Are they just for fun, or do they also reward Diamonds?

Gordon: You nailed it, it’s both! We have a handful of delightful mini-games, one for each character’s storyline. They’re mostly a fun way of showing how characters from the Crypt world would interact in our modern setting.

It always cracks me up seeing the NecroDancer and Cadence—normally at odds—working together to make burgers in our Burger Time mini-game. These antagonists, who usually fight each other, are now trying to survive a lunch rush and assemble burgers in a kitchen. Then there’s Dove, leading a yoga session, while Cadence tries to bend her body into different shapes to keep up with the class.

We also have harder variants of each mini-game, so players can come back, prestige, and earn a perfect badge for each one. And as you mentioned, they reward Diamonds that help unlock additional content.

Q: On the subject of progression and unlocks, in Rift, we’re mainly progressing by earning diamonds, whereas in Cryp, there was a lot of roguelike meta-progression. Was that something you were interested in exploring with Rift? Things like gaining more health or equipment?

Gordon: We did look into it and we’d love to explore more in the future. For Rift today, we wanted to focus on making tracks that are musically accurate and ensuring that whatever you do in Rift contributes to your progression. As we mentioned, we don’t force you to play one track after another. Certain tracks may be locked at the start, but you quickly start unlocking content, and then you get to decide which tracks you want to play.

While Rift of The NecroDancer is in the same Crypt universe, it’s not a direct sequel. Rift of the NecroDancer doesn’t have roguelike progression, instead, progression in Rift works how you’d expect from a rhythm game. You play tracks and earn Diamonds (a Crypt throwback) to unlock more tracks and earn more Diamonds. Minigames and boss battles can be unlocked with Diamonds too, so you can play them as part of story mode or dive right into track select to quickly unlock them. We’ve balanced the game so even players on easy mode can unlock all of the content, with impossible difficulty, Remix Mode, and some more hardcore modifiers locked to higher Diamond amounts. We want players to access all our content quickly and play how they like! There may even be some secret ways players can find to unlock the content even faster.

Q: Can you talk about your plans for Rift of the NecroDancer’s post-launch support?

Gordon: We’ve got some really cool collaborations lined up, including banging indie classics to larger IPs as well. The plan is to offer players free content as well as premium song packs! Can’t say much more but it’s gonna be so rad, I can’t wait for everyone to see!

Q: Is there anything we didn’t touch on that you’d like to mention or any last thoughts you have?

Gordon: I think your questions were awesome. Personally, I’ve never worked on a game before where the core concept proved to be so solid so quickly. Two or three years ago, when we were making the prototype, we played it immediately and thought, “Yes, that’s it! That works! That’s awesome!” Every year since then, I’ve thought, “This game is done, it’s ready!” But then people found more opportunities to improve it, and we realized, “No, no, we need to let it cook a little longer.” The next year, I’d think, “Oh my God, I thought the game was ready last year, but now it’s absolutely singing! It’s great now!”

We’ve spent more time creating new monsters that hit notes we couldn’t before and increased the fidelity of monster placement. We also now have a whole new level editor, which I’d really love to highlight. It’s the exact level editor we use to make tracks internally, and we’re sharing it with the community on day one. We’ve already been sharing it with our playtesters, and we’ll support it on Steam for custom tracks, music, and backgrounds. We’re already inspired by what people make in our Discord and are excited to see what players create once the game launches.

The whole project has felt like that: every time I think we’re done, someone like Danny, Ryan, or the level designers will come to us with a new improvement that makes the game so much better. I’m just really excited to get it into the hands of players.

I’m so hyped for people to play it. I can’t wait for February 5 to come around, and I can’t wait for folks to see what else we’re up to as well.

[END]

Leave a Reply