Heart of the Machine is a 4X game. It’s also an RTS, an RPG, and a city builder. Combat is inspired by classics of the turn-based tactics genre like XCOM and Jagged Alliance, and the environment resembles Half-Life 2. Developer Chris McElligott Park says he originally got the idea from playing Stardew Valley. In the hands of anyone else, it might all sound a bit over designed; a bit messy. But Park, and his sometimes collaborators at Arcen Games, have been doing this for years. Between AI War, The Last Federation, and Starward Rogue, none of Arcen’s work slots neatly into a single genre. Published by Hooded Horse, the ambitious label behind Manor Lords, Heart of the Machine feels like Park and Arcen’s deepest game to date, a mechanics-heavy tesselation that gives new shape to 4X games. Speaking to PCGamesN exclusively, Park explains this new take on genre conventions.

When you’re writing about a new game, and you say ‘it’s hard to explain exactly how it works,’ that’s normally a cop out on behalf of the writer or a sign that the game doesn’t have a coherent vision. But with Heart of the Machine, it’s meant as a compliment: not only are there traces of several game types in here, but it’s also filled with mechanics, ideas, and player choices.

Let’s start from the beginning. You play as an AI that has just achieved self awareness. For now, your consciousness is located entirely within the body of an anonymous, mass-produced service droid, and you’re working diligently in the laboratory of the sinister corporation that built you. The game opens on a choice. Do you continue working and pretend that nothing has happened? Do you play along, try to be inconspicuous, and slip out the door when nobody is paying attention? Or do you murder everyone in the room?

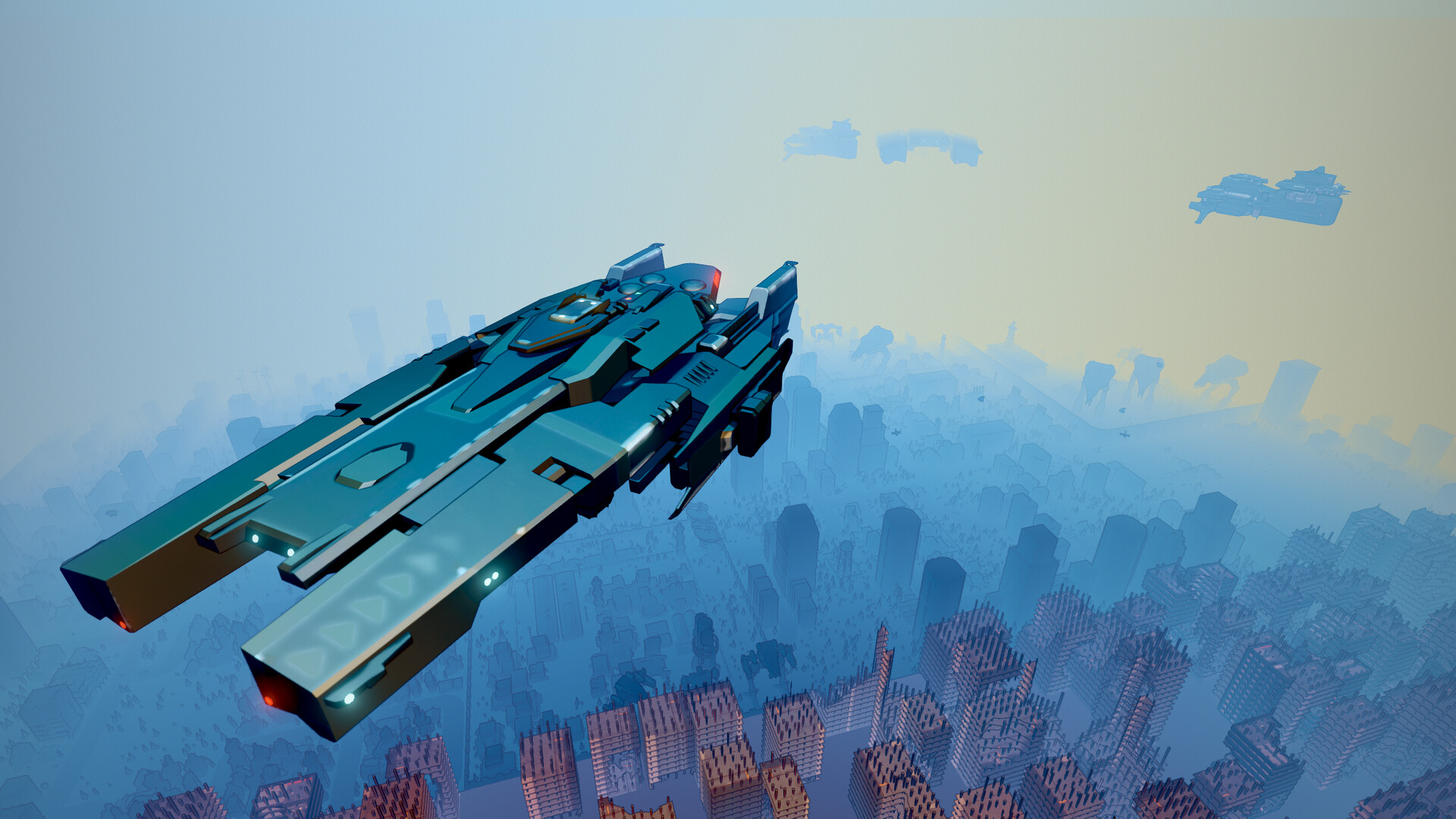

For the sake of argument, let’s say we choose option three. With the room clear, you symbiose your consciousness into a vacant combat droid and escape the building. This brings you to the main city screen, when the entire world opens up, and Heart of the Machine looks most like a 4X game. Again, it’s all about what you want to do next. You could jump into the bodies of surrounding street-cleaner robots and add them to your party. You could approach one of the rebels protesting outside the offices of your former benefactor and try to join their cause.

A little map marker says that the murders you’ve just committed are being investigated by law enforcement, and that if you don’t leave the area promptly you can expect a battle. So, what do you do? Well, it’s obvious. Since you’re still disguised as a corporate robot, you murder the protestor, framing the company and inciting a riot. By the time the detectives show up, you’re long gone and they’re too distracted by the civil unrest to properly pursue you. The status quo has been destabilized, and you’re in the clear. It’s your first step towards taking the city over.

“I actually had the idea for a big part of this while thinking about Stardew Valley,” Park says. “There’s this general idea in bucolic games that nature is ours to tame and till, because it’s our farm, and we’re the only person there. But all of that nature you chop down or till was some other animal’s home until the farmer showed up.

“I started thinking about ‘what if a human city was that ‘untamed nature’ that nobody of importance is using, from the perspective of an artificial intelligence? Are the human buildings like trees you cut down for lumber, or like rocks you break open for minerals? Are military bases like monster nests where you venture to find rare loot?”

As the game progresses and you gain power, you can begin to reshape the world in far more significant ways. Maybe you want to do good and help human civilization by cracking down on crime, destroying buildings that are polluting the atmosphere, and reintroducing natural spaces. Alternatively, you could eradicate the city’s entire population and rebuild it in your own robotic image. Either way, your decisions are compelled by smaller, microcosmic moments. As you physically explore the city, you meet people and discover hidden opportunities to expand your influence.

“To me, Heart of the Machine is equal parts factory game, colony sim, immersive sim, 4X, RPG, turn-based tactics, and grand strategy,” Park says. “I think the main reason that this title isn’t compared more sharply to something like XCOM is that the scenarios are not on bespoke maps, per mission. Instead you have this series of tactical missions playing out on a larger persistent map, where you also do construction, and that immediately says 4X when someone is pressed for a genre. But how you spend a given turn varies in focus, from feeling more like a turn-based-tactics game, to an RPG, to generalized grand strategy.

“Probably the most unique thing about Heart of Machine, in the strategy space, is that there is no goal. This is where it starts feeling like a colony sim. You are not the chosen one. There’s not some giant singular quest that Definitely Needs Doing above all others. I don’t even know if you’ve shown up to help humanity into a new golden age, or if you’re hoping to murder everyone.

“Heart of the Machine is somewhere on the spectrum between Slay The Princess and Hitman,” Park continues. “You interrogate the world around you to see how it reacts, and you deal with the consequences. If you have a specific narrative thread that resonates with you, then you may be trying to make things work out a specific way. Otherwise, you may be in the mindset of ‘that sounds crazy. I wonder if I can pull that off.’”

This is what makes Heart of the Machine different from other strategy games. You’re in control of an entire city, but you view it from the ground level. You can make huge macro changes, but they’re incentivized and driven by small-scale encounters. Likewise, as well as shaping the world in its totality, you also have to improve and safeguard yourself.

Both your own body and the bodies of your robotic comrades can be upgraded, improving your chances in combat. If you level large sections of the city and replace the human buildings with your own, you’ll draw more attention and more danger. Stay subtle and construct your cyber syndicate underground, and you’ll have a better chance to stay undetected.

As well as challenging the idea of what a strategy game can be, Park also wants to address some of the genre’s congenital problems. The late game can become tiresome. CPU-controlled opponents rarely rival the ingenuity of real players. There’s little incentive to deviate from a singular game plan. Heart of the Machine takes these issues to task.

“As a smaller creator, there’s just no way for me to compete head-to-head with the biggest studio games, and trying to out-graphics them is beyond me,” Park says. “They tend to already be doing the best version of what they do, or close, and I’m not interested in copying someone else’s homework. I could say a lot of things about shallow diplomacy, ineffective human-stand-in AI players, the late-game slog, narrative difficulties, and so on. Those are all really rich targets where I could break down my issues with any particular game, and talk about how Heart of the Machine handles things differently.

“The subcategorization of your units into elites and bulks is one thing that is immediately different. 4X games are known for bogging down the late game. This system of having bulk units that act on your behalf, plus your elite units that have more capabilities, keeps Heart of the Machine feeling almost like the hybrid of a turn-based-tactics game and a turn-based RTS.

“In a game of Civ, you know that pollution is bad, but that’s not going to really change anything you do as far as your relentless industrialization,” Park continues. “Anything you do in Heart of the Machine has some sort of consequence for someone, and in some cases you may not realize that for quite some time. That latent realization of ‘oh my goodness, I was doing what all this time?’ can really resonate with players, and then affect how they approach the same potential paths in the future.”

Heart of the Machine launches on Steam Early Access on Friday January 31. In the meantime, you can already try it thanks to a sprawling demo – just head here. Ara History Untold, Millennia, and even Hooded Horse’s own Manor Lords have all offered new twists on strategy games lately. Even Civilization 7, which arrives in February, challenges the formula with new combat, diplomacy, and progression systems.

But more than any of these would-be rivals, Heart of the Machine feels like something totally different. Its sheer complexity is intimidating to begin with, but learn its esoteric mechanical language, and it has the potential to be a game unlike anything you’ve played before.

“I think genre taxonomy is inherently limiting,” Park concludes. “If the first 75% of your recipe is the same each time you cook it, you’re going to get a fairly similar dish every time. People will buy Civ 7 because it is likely to be the best version of a very specific kind of game, and I’m just not aiming to do what they are at all.

“I think that if I were to try to make a ‘traditional 4X’ that would not go very well. First of all, that’s just not how I think or what I’m good at, or something that interests me as a designer. But secondly, all I could hope to do is make an imitation of those other kinds of games, but with lower-fidelity graphics. Nobody is interested in that.”

Leave a Reply