Huddled into two groups, a handful of players stand ready within a clearly delineated arena. Perhaps there are goals of some sort marked out at each end, or a net running down the centre. There’s probably a ball in the mix somewhere. The shape of a sport is immediately recognisable; something that videogames from Speedball to Windjammers and Blood Bowl to Rocket League have taken advantage of in order to invent sports of their own, set in fictional worlds that often revolve around that one game. Whether it’s a dark future in which a brutal bloodsport helps distract from the dystopian reality or a modern society preoccupied with the battling of trained animals, in order for the fiction to make any sense, developers need to come up with the rules for a game that could feasibly hold the attention of an entire world, as the most successful sports do in ours.

Speaking to designers who’ve taken on this challenge, many tell us that their fictional sport game was the most difficult one they’ve ever made. Which raises an obvious question: why do it in the first place?

While some say it’s a result of being sports fans themselves, that seems to be the exception rather than the rule. More representative is Greg Lobanov, maker of Chicory and Wandersong, games about art and music respectively – “things I already knew a fair bit about” – who is now tackling the world of sport, in the forthcoming Beastieball. Lobanov acknowledges that he’s coming at the topic from an outsider, “fish out of water” perspective. While he went to a high school that prioritised athletic scholarships, he “didn’t fit in at all”, being less interested in the real thing than with its depiction in anime and manga, where sport is a popular subgenre. “I grew up on Prince Of Tennis,” he recalls

Subscribe to Edge Magazine

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine #395. For more in-depth features and interviews diving deep into the gaming industry delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge or buy an issue!

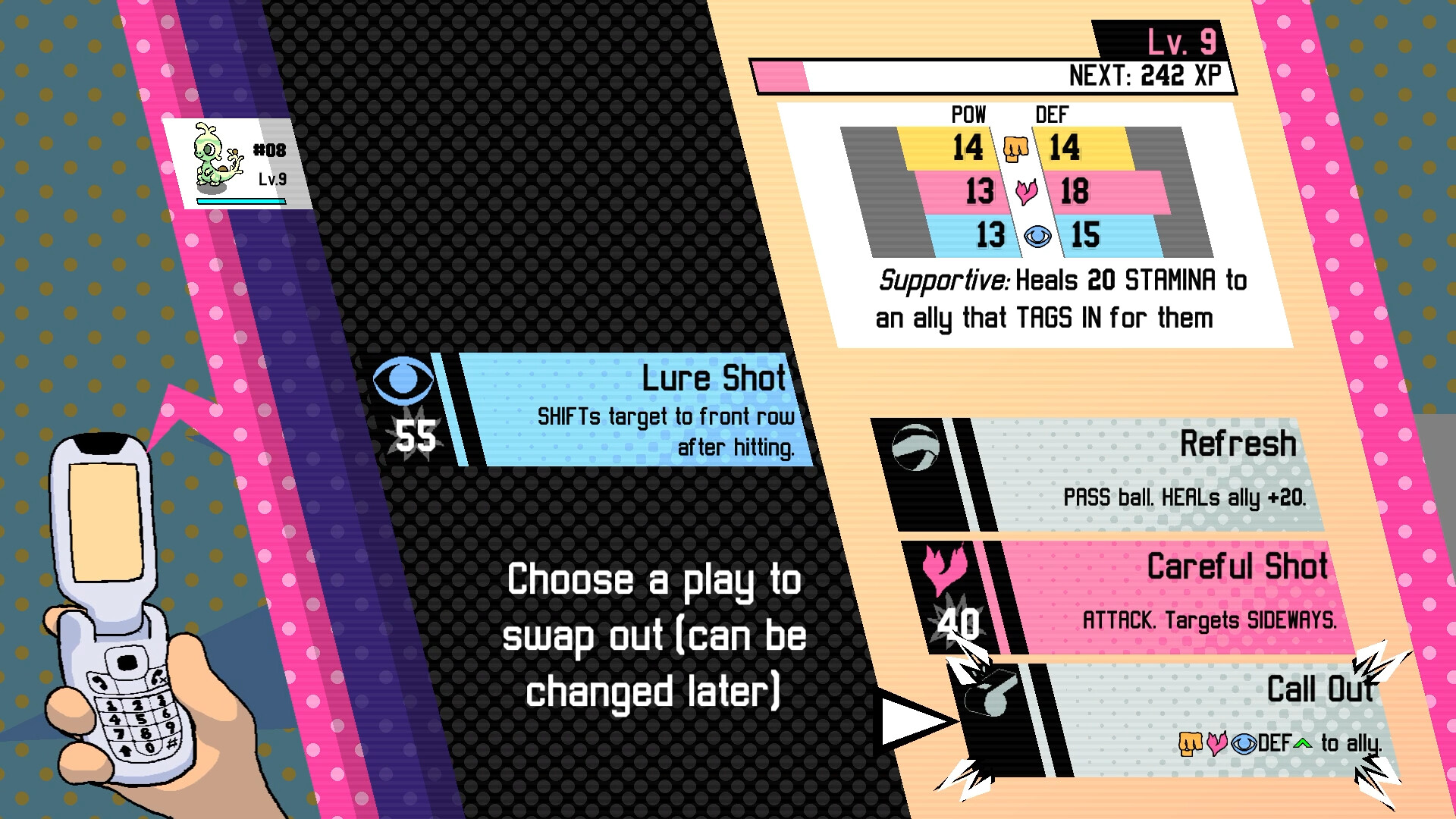

But for years he has wanted to make a game, initially inspired by his experiences cycling across the US, that focused on community and cooperation. “A game about building a team.” Something that allowed the player to put together a roster and strategise around their individual strengths and weaknesses. “And sport seemed like a really natural fit for that idea.” As for how’d he present it, Lobanov looked at a world typically driven by split-second decisions and reflexes, and landed on a perhaps unlikely answer: a turn-based tactics game. “I wanted a game where you win or lose based on your understanding of the players in your team and how they work together.” The easiest way to represent that was through player stats, he reasoned, and that in turn lent itself to a game of strategy. And remarkably, Lobanov is not the first developer to come to this conclusion.

A year before Beastieball was unveiled at 2023’s Day Of The Devs event, the same summer showcase introduced us to Ustwo Games’ Desta: The Memories Between. Asked why a developer best known for creating newcomer-friendly mobile puzzle games would decide to make a turn-based ballgame, Desta lead designer

Joel Beardshaw explains: “We were really interested in the idea of – and I know it sounds really silly – just passing a ball. And the requirement to use people in conjunction with each other: ‘I’ve picked up this ball, but I can’t throw it anywhere useful, so I’m gonna pass it to my mate’.” Ustwo similarly settled on turn-based tactics as the best way to realise this vision of teamwork. In every other respect, though, the two developers reached very different conclusions.

Having decided he wanted to make a sport strategy game, Lobanov considered a variety of real-world options. “Soccer doesn’t really work very well [for a turn-based approach]. American football got a lot closer, because it has a nice rigid pace, and lots of very distinct character classes built into it.” Eventually, he found his answer in – what else? – a sports anime. “We watched Haikyu!! during the pandemic, and that got the wheels spinning in a big way, particularly on how volleyball was a turn-based game.” The dynamics of volleyball – by which players take turns to launch the ball over the net and wait for it to come back, all the while coordinating their position with teammates – lined up perfectly. “That solved a bunch of problems, all at once.”

Desta, meanwhile, is essentially an adaptation of dodgeball as a tactical skirmish game. Small teams move around an eight-by-eight grid (the same size as Into The Breach’s maps, or a chessboard) trying to eliminate one another, not with weapons but with thrown balls. “A ball is a magical thing,” Beardshaw says, “in any game.” He points to the inevitable moment in a game of football or rugby – “I’m not a big sports person, but I watch the odd match” – when the physical properties of a ball cause something unexpected to happen, pinging off a crossbar at an odd angle or sailing farther through the air than seems probable. Desta, for its part, features manual aiming: you can line up trickshots to strike rivals hidden behind cover or rebound a ball into the hands of a waiting teammate.

There are other benefits to applying, as Beardshaw puts it, “a sport framework” to a design more commonly used for combat in videogames. He recalls an observation made by senior designer Jonathon Wilson, who’d previously worked on VR tactics game Augmented Empire: “Other tactics games really struggle to get the player to move around an arena, because you find the best defensive position, you put your XCOM characters there, and that’s it. They had to do so much, in the games that he worked on before, to draw the players out, to get them moving. But the fact that you’re throwing balls around automatically requires you to reposition in every single turn – and without having to make up special magical rules such as ‘the ammo only spawns here’.”

Beastieball’s central game presents more like RPG combat – Pokémon is the most obvious reference point visually, though positioning your team members is much more of a consideration here. “It took a long time to try to figure out the rules,” Lobanov says. “There were a lot of ways to do it where it just was totally unreadable.” He ended up leaning on familiar concepts: Beasties have stamina meters, essentially HP that can be worn down by ‘attacking’ them with the ball. “What I’ve realised is that any turn-based strategy game, like a Fire Emblem or XCOM, those are basically sports games,” Lobanov says.

“I mean, sport is basically war.” Trace back the origins of most team sports, his argument goes, and you’ll find “a simulation of combat”. And when war and sports are boiled down into videogame-friendly rules, the likeness becomes even more pronounced. “That’s what happens to war when you do game design to it.”

Which doesn’t mean that Beastieball is a violent game, exactly. If you do deplete a rival’s stamina bar, “they’re not eliminated from the game – it just means they’re tired for a little bit.” This is intended to shift the strategic focus away from prioritising targets, as you might in an XCOM encounter (thin out the ranks of weak Sectoids, or remove the threat of a Muton Berserker?). Instead, it’s more about considering the various ways of scoring a point, not all of which involve dealing damage, that will be your most likely path to victory.

After all, a plucky team can lose repeatedly before rallying for a spectacular comeback in the final, vital match; that’s rather more difficult if each encounter involves fighting to the death. Indeed, it was precisely this quality that Supergiant Games found attractive when, after the release of Bastion and Transistor, the studio decided its third game would revolve around a fictional sport. “There’s a lot of media where the central source of tension and drama comes from characters getting killed off,” says designer and writer Greg Kasavin. “We wanted to explore this other side of things.”

“We have always been very interested in failure as a core part of our games”

While Pyre might have seemed like a change of direction for Supergiant, given the combat-focused action games the studio had made up to that point, Kasavin sees a consistent throughline: “We have always been very interested in failure as a core part of our games.” Dying in Bastion might earn you a winking comment from Logan Cunningham’s husky narrator, while in Transistor it removed one of your weapon’s ‘Function’ abilities, forcing you to try another approach. “And failure is a core part of sports.”

The aim was to make a narrative that adapted to the outcome of each game, rather than forcing you to start over after a loss. “We would narratively support every possible outcome along the way, and culminate in an ending sequence with hundreds of millions of permutations, so the story would feel personal and unique to each player,” Kasavin explains. “The sports-like framing was essential to this, both for the zero-sum structure – in order for someone to win, someone else must lose – and for the non-lethal nature of the competition. In order for rivalries to form, and for characters to have to pick themselves up from defeat, characters have to keep living.”

Supergiant has continued to play with these ideas, Kasavin says, even as it has returned to games about fighting. “Many of the central ideas in Pyre – the drive to escape from endless purgatory, having to pick yourself up after a tough loss, having to contend with rivals again and again – were so compelling to us while working on that game that we kept exploring them.” While the studio’s next game found its own fictional reasoning for all these things, in the cycle of death and rebirth that powers both classical myths and Roguelikes, Kasavin believes Hades “never could have happened if not for Pyre before it.”

Its development also left a more personal impact on Kasavin himself. “Since working on Pyre, I’ve become much more of a sports fan, and am super-invested in American football, for example,” he says. “The key for me is to get close enough to the sport to know the personal stories of the players, and then I’m hooked.” Which is, of course, precisely the fuel on which Pyre runs.

Kasavin points out that in Pyre’s fiction the game of Rites isn’t technically a sport, much as it might look like one, with its two teams trying to sneak an orb past one another and into the opposing goal. Rather, it is an ancient, occult means for deciding who is worthy to escape exile in this world’s purgatory-like Downside. (“We were fascinated with how sports are as old as civilisation itself, and are like rituals,” he explains. “There are ancient sports, such as the Maya Ballgame, which blur that line.”) Nevertheless, within Pyre’s fantastical setting Supergiant managed to find equivalents for many familiar sporting concepts: rival teams, commentators, a loose league structure with promotion and relegation. Useful narrative tools, as demonstrated by everything from Ted Lasso to The Karate Kid – and indeed by the real thing, those endless, ongoing soap operas that Kasavin learned to appreciate through the process of making one.

“These feelings are a large part of why I watch sports to start with,” Ian Hardingham says. “When you’re really into a league, so much of it is fascinating. The weird tradition, the moment-to-moment action, the behaviour of the people involved. So it felt extremely ripe.” In the days when he and fellow co-founder Paul Kilduff-Taylor made games together as Mode 7, sport was a “company ritual” – American football in particular. “I loved that it was on late at night. It just felt so exotic.”

So when the studio came to make a followup to its breakthrough, Frozen Synapse, a sport game seemed like the obvious choice – not least because Hardingham had been playing Chaos League, Cyanide Studios’ unlicensed digital take on the Blood Bowl tabletop game. “I really enjoyed that. And I also thought there was plenty wrong with it.”

After no small amount of wrangling, Hardingham eventually found a way to translate Frozen Synapse’s ‘simultaneous turn-based’ design (each turn is programmed by both sides in advance, before watching their carefully laid plans bump up against one another) into something roughly analogous to American football. Frozen Cortex has you giving orders to a team of players, trying to seize control of a ball and carry it an endzone, while anticipating the actions of your rival. It can be played against a human, which has the poker-like crackle of trying to read an opponent’s mind, but finding a match might be a little difficult these days. Instead, you might be better off trying Cortex Manager, a Football Manager-style mode added after the game’s initial release that simulates a league populated by randomised AI teams.

“Sport is a narrative-generative medium. That’s just what it is,” Kilduff-Taylor says. The combination of in-game rules and wider context – that soap opera of leagues, teams and players – dynamically spits out story moments. And we don’t need much fuel to access them. Kilduff-Taylor remembers youthful games of Speedball, along with EA’s NHL Hockey on Sega‘s Mega Drive where entire careers and rivalries were dreamed up from the sparsest details. “The Speedball teams had those wonderful names, some of which I think were, maybe, racehorses?” Kilduff-Taylor says. “That can be very evocative, just a name and a logo.”

Part of the reason we can build these stories out of so little, perhaps, is that sport narratives tend to follow a similar pattern – one that’s only reinforced by the natural shape of videogames. “You learn mechanics, you unlock new stuff, your character gets better and more powerful across the course of the game,” says John Ribbins, co-founder of Rollerdrome and Laser League developer Roll7. “So it’s really difficult to tell a story where it’s like: ‘You’re a pro who falls from grace and gets worse and has to learn how to deal with just enjoying a sport as an amateur now’. That wouldn’t make for a fun game. You want the story to be, like, you start shit and then you end up being really good, and you win – that rags-to-riches, amateur-to-professional arc.”

Looking at some of our other examples, that description certainly seems to fit Beastieball, which tells the story of a kid taking the reins of their washed-up home team of Beasties and trying to take them all the way to the top. But Lobanov is set on using these tropes to interrogate the nature of sport, much as he did with music and art in his previous games. He rattles off a few themes he’s interested in: “The relationship between players and the game, and going professional. Even just, like, the existence of money and capitalism, how that intersects with it.”

In the world of Beastieball, this sport is “a natural, beautiful thing”, the creatures that play it having evolved specifically for this purpose. Your motivation for breaking into the big leagues is to convince its leaders not to bulldoze a local nature reserve where the Beasties play freely, in order to build a massive stadium dedicated to the sport. These warring impulses are a familiar trope of their own, especially in the strain of future-sport science fiction that informs Roll7’s shooter-skater Rollerdrome. In that game, the sport is owned and operated by Matterhorn, a giant corporation trying to distract from its evil deeds – what in the real world we might call sportswashing. Was the commercialisation of sport, and its knock-on effects, something the developers were concerned with as they made the game? Ribbins looks around the meeting room, deep in the London headquarters of Roll7 parent company Take-Two. “Sitting in the giant offices of a giant corporation, while we’re all miked up, I don’t feel like I should comment on this,” he laughs.

“They’re really action games about mastery.”

Being owned by Take-Two, via its Private Division label, makes Roll7 a kind of distant cousin to 2K Games. Something these two relatives have in common, albeit at very different scales: they both made their names with sports games. In Roll7’s catalogue are two futuristic bloodsports, Laser League and Rollerdrome, as well as three OlliOlli games – skateboarding is the one sport Ribbins actually follows. “We had this chat recently, actually, a bunch of people from the team. Most of the things we’ve made are sports or sports-adjacent – I think Not A Hero, really, is the only exception. But a lot of the time, it’s sort of just a wrapper, right? They’re really action games about mastery.”

For all the studio’s history of making games about sports, fictional or otherwise (and even OlliOlli World‘s vision of skateboarding is rooted in a fantasy realm of Skate Gods and Wizards), this is how Ribbins ultimately sees the topic: “A convenient framing device. We made a cool, tight series of mechanics that are fun to execute and master and get a score for.” And presenting it as a sport provides a handy narrative explanation for all that. Ribbins uses the example of Rollerdrome: “If that wasn’t a sports game, it would just have to be abstract. Why are you murdering people on roller skates, in an arena, and getting a score for it? In some ways that’s the only way to make it make sense.”

This is pretty much exactly how Laser League ended up with its future-sport theming. It started life as Ultra Neon Tactics, a party game more akin to Nidhogg or Starwhal, where four coloured dots – two pink, two green – positioned lasers to take out their opponents. After years of playing it at events and in pubs, Roll7 found a publisher and decided it needed a “framing [with] more massmarket appeal.” The studio looked at Rocket League, already on its way to becoming a sport in the real world, and simply followed suit.

The concept of sport as a thematic framework comes up in almost every conversation we have. Kilduff calls it “a box that the game can go in” – a way of grounding raw design in the player’s brain, so they can see the kinds of stories they might be able to tell with it. Lobanov talks about it in terms of “what we get for free”, in terms of justifying any rules necessary to keep a game balanced. This was on Supergiant’s collective mind, too, as it conceived Pyre. “We thought a lot about how real-life sports are often filled with obscure rules and exceptions that grew over time,” Kasavin says. “The Rites gave us an opportunity to create a set of rules like that and have them feel grounded in the world of the game.”

After all, while we might question the invisible walls at the edge of a combat arena or open world, no one thinks about the ones at the edges of a football pitch. Developers variously reference the offside rule, Formula One’s bans on certain types of tyres, the power-boost systems that reward Formula E drivers with extra speed, and the ever-shifting regulations around baseball. “Once teams find an optimal way to play a sport, it really matters whether that is fun to watch or not,” Lobanov says. “And so sometimes, even if it’s strategically interesting, they have to change the rules.”

In games and sports alike, these rules are, ultimately, an arbitrary decision on the part of a designer, Hardingham argues – the key in a videogame making sure they’re not exposed in a way that feels wrong to a player. “When you’re doing, like, men with guns, or an RPG or something, you kind of take something that’s somewhat real-world, and you have to find a way to structure the game around it,” he says. “Whereas with a sport, of course, it’s already a game. And this structure just makes more sense. So I think that’s one of the reasons to try and invent a sport.”

No wonder Beastieball has gradually grown into “a game about game design,” as Lobanov tells us. “Because sport just seems like such a natural way to explore that.” It’s easy to identify some potential thematical strands here: the ways in which Pokémon’s design has failed to evolve, perhaps, and the elite squad that Lobanov has gathered in the form of Wishes Unlimited. But he’s currently most interested, he tells us, in the question of what it means to go pro. “You’re hitting a ball around, and then suddenly it’s for millions of dollars and for a global audience. What happens in that transformation? What does that feel like, as a player?” he says. “You’re doing something that was made to be done for fun, but you’re doing it professionally. Which I can also relate to, in a totally different way. Making games, for me, is really fun, but now I do it as a job.” For Lobanov, that’s been a helpful way into a topic he was approaching from the outside – and it’s challenged some of his prior assumptions, about sport but also game development. “It’s probably changed, a little bit, my relationship with my work.”

And, like the other Greg before him, it’s changed Lobanov’s relationship with real-world sport. “I’ve started keeping up with sports news,” he says. It’s all useful for inspiration. “All this stuff that happens every year that’s so crazy I could never make it up,” he says. “When I hear about one of those stories, I’m always thinking, ‘How can I put this in my game?'” Not that every developer falls in love with the subject, of course. When we ask Ribbins whether sport figures into either of the major projects Roll7 currently has in the works, he replies with a smile: “I don’t think we’ll be chatting about sports games in four years’ time.” If the history of videogames is any indication, though, plenty of other developers – whatever their personal athletic backgrounds – will be ready to step into that gap, and add a sport of their own to a storied and fertile field.

That’s sports games, but what about blockbusters? AAA – Developers discuss the three little letters that have shaped an industry: “It’s a stupid term. It’s meaningless”

Leave a Reply