It’s easy to reduce Sorry We’re Closed to a checklist of Silent Hill 2-isms. Fixed camera angles? Check. Psychosexual monster design? Check. Filthy, rust-eaten environments? Check. However, like the celestial beings that make up its cast, this familiar visage is only skin-deep. Whereas others seek to replicate the formula to pay homage or to recreate it for modern audiences, indie studio À La Mode is incomparably brave. This scion stands before the sacred cow that birthed it and dares to continue the conversation that Silent Hill 2 began two decades ago.

In Sorry We’re Closed, love is an ephemeral state that eludes both the divine and the infernal. It is a retro survival horror game about how love changes us, wherein the transformative effects of love manifest as body horror, an irreversible change that demands a high price. Acts of love are often violent, bloody, and morally reprehensible. Despite (or rather, owing to) the pyramid heads, nurse uniforms, and abstract daddies, Silent Hill 2 follows the same philosophy.

James Sunderland’s love for his wife drives him to commit unspeakable acts. It is the catalyst that transports him to Silent Hill, a psychological prison of self-flagellation and punishment. As both prisoner and jailer, self-acceptance is the key to James’ freedom, forcing him to confront the fatal harm he inflicted upon the one he loved. Silent Hill’s facsimile of Mary grants him forgiveness, the fog lifts, and he leaves hand in hand with the guiltless herald of truth and acceptance: Laura.

Like Silent Hill, Sorry We’re Closed positions us in a specific place. Instead of a sleepy resort town in Maine, New England, we are in London, Old England. While James is functionally a tourist, Sorry We’re Closed’s Michelle is the lovelorn twenty-something who runs the check-out at the local convenience store. Her shifts are bookended by perfunctory visits to the local indie vinyl store and greasy spoon before she retires to her one-bed apartment. Michelle is no outsider here; she is a valued member of a thriving community, yet she remains psychologically isolated by heartbreak.

Michelle’s descent into the underworld isn’t to do penance but it is borne from guilt. Her internalized regret over her break-up leaves her vulnerable to a nighttime visit from the Duchess, a powerful demonic entity that lusts for love. This fleeting encounter opens Michelle’s third eye, allowing her to slip between realities and discover a Miltonian plane of existence where the fall of angels is considered the ultimate break-up. Hell is empty, and all the devils are heartbroken.

Sorry We’re Closed communicates Michelle’s power in this world using Silent Hill 2’s own thematic naming conventions. It’s common knowledge that “Sunderland” refers to James’ fractured mental state, giving rise to the ‘sundered land’ of Silent Hill’s Otherworld. Michelle doesn’t have a surname, but she doesn’t need one. Her forename, derived from Hebrew as “one who is like god,” is enough to declare her power over angels, demons, and the Luciferian Duchess. She is the object of desire, but she refuses to be objectified. Her capacity for love – and capacity to inflict pain through that love – makes her an active force within her own Otherworld. The most powerful weapon at her disposal is an esoteric rifle known as the “Heartbreaker,” charged by all the little hurts inflicted by the smaller weapons in her arsenal to shatter the locked, fragile hearts of fallen angels desperate for love.

James is not an object of desire in Silent Hill; rather, he is besieged by it. The eroticism of Masahiro Ito’s monstrous creations sits at the forefront of Silent Hill 2’s critical landscape. Often subject to reductivism, Silent Hill’s projections of Mary are multifaceted; some represent sexual frustration; others, the verbal abuse Mary inflicted upon James as her illness progressed; but only one is “born from a wish.” Like the Duchess, Maria’s character design invites sexualization on the player’s part yet her intrinsic sexuality amounts to Christina Aguilera’s attire at the 1999 Teen Choice Awards and a carefully placed butterfly tattoo. It is as performative as the Duchess’ drag queen regalia, masking the true form that lies beneath.

However alluring the Duchess may be, Michelle’s true temptation appears each time the player interacts with a save point. These phone boxes require the player to speak to the Operator, a two-headed, snake-tongued demon of indeterminate gender who urges the player to strike a Faustian bargain to bring down the Duchess. Michelle’s reward? A second chance with her ex, the daytime TV star that haunts every television screen. This is, ostensibly, Michelle’s Maria. “All of your pain gone, in the safety of her arms,” the Operator promises – but anyone who has had their heart broken knows that nothing is so simple.

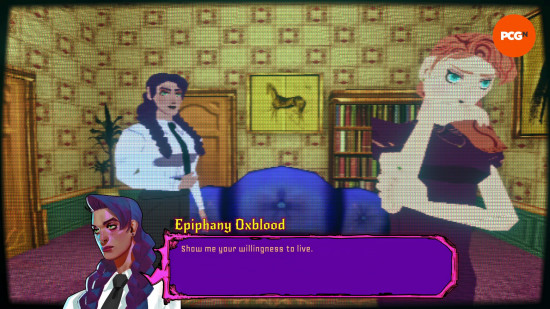

It’s been three years since Michelle and Leslie separated, and there’s no question who’s come out better off. Leslie’s performance as Epiphany Oxblood has viewers glued to the screen, propelling her to stardom while Michelle stagnates as a heartbroken singleton. In reality, reparations between these two estranged lovers require more than a snap of demonic fingers. “Her career doesn’t have to go that far,” the Operator assures Michelle. Sorry We’re Closed invites the player to strip the aspirations from Michelle’s beloved so that she can have her. It is possession; it is ownership; it is not love, but is borne out of it. It is as doomed as James choosing to leave Silent Hill with Maria, only to hear her cough.

If we conclude that this action is deeply immoral, it begs the question of what isn’t. The truth is that there are no objectively moral choices in Sorry We’re Closed. Each one is cloaked in an ambiguity that circles back to the irrationality of love itself. It asks the player to consider their own philosophy and definition of love, then challenges them to differentiate it from codependency, obsession, even hate – or if it can even be separated at all. The Duchess sees a loveless existence as an indignity, yet their desperate, millennia-long quest for love is a kind of debasement in itself.

Consider the Dream Eater and Chamuel, two celestial beings who have loved each other for millennia, now on opposite sides of the divide between angels and demons. Their enduring connection has left Chamuel diminished and on the cusp of exile from Heaven. Is this a star-crossed romance, or an abusive relationship that’s run its course? We later learn that angels and demons can’t touch without inflicting great pain upon each other – and yet, the sweetness of that pain is intoxicating.

“That’s when things got exciting,” Chamuel says, as the player stares down a pitch-black tunnel ringed with metal spikes: a bottomless pit, or a wide-open eye. “I liked it.” Both Silent Hill 2 and Sorry We’re Closed are replete with BDSM undertones, but the interplay of bondage and freedom is made manifest in Chamuel. His love for the Dream Eater unshackles him from the hive mind of The Divine, but it also leaves him vulnerable to death.

Rather than allow Chamuel to give up his immortality for the sake of their love, the Dream Eater goes to extreme and abhorrent lengths to stop him. He smears Chamuel’s bloody entrails across the same gilded corridors that musealize his lover’s countenance, decapitates him, then repeatedly flings his limp corpse at Michelle in the subsequent boss battle. In the Dream Eater’s eyes, this is the only future a mortal life will bring Chamuel. The Dream Eater is James, performatively killing Mary over and over because he cannot face the inescapable truth of her death. And yet, without Chamuel’s love, the Dream Eater’s self-destruction is assured.

Silent Hill 2 is a love story. The best dating sims often go hand-in-hand with survival horror. Perhaps love is the most terrifying survival horror of all because it is impossible to survive. At worst, you must confront the inevitability of death; at best, you are irrevocably changed, so that the ‘you’ is no longer ‘you’ but ‘us.’ For Chamuel, though, this pain is worth the pleasure of love. Signalis, another modern survival horror classic, understands this unequivocally. The snapshot of Ariane and Elster dancing in a gentle embrace mirrors the grainy videotape footage of James and Mary in marital bliss at the Lake View Hotel.

Amid all the horror James and Elster endure, these transient moments are framed to justify their struggle. We don’t have any analogous moment in Sorry We’re Closed; the closest we come to it is the TV show starring Leslie, whose script is a dramatic reenactment of her break-up with Michelle. The series finale is predicated on dialogue choices and the outcome of the relationships Michelle assists along the way. Sorry We’re Closed doesn’t take a stance. Instead, it requires the player to decide if that struggle is worthwhile.

It also directly challenges the idea that Maria is the counterfeit version of Mary, and therefore only deserving of rejection. “It’s not you who’s being wanted. It’s a false concept of what you symbolize that is desired,” Michelle’s best friend, Robyn, tells her in a car-ride conversation concerning the affections of the Duchess. “Love is like that anyway,” Michelle counters. “We always make an ideal version of the person we fall for. And then there’s reality.” We can choose to be the Repenting Demon, prostrating ourselves at the altar of that idealism. Silent Hill 2’s ‘good ending’ has Maria making that prostration. She dresses in Mary’s clothes, mimics her vocal affectations, and presents herself to James as the paragon recorded at the Lake View Hotel.

James is right to canonically reject Maria, but Team Silent offers no alternate reality in which she can extricate herself from James’ judgment. Maria is a monster, but her personhood separates her from the inarticulate psychosexual creations of James’ psyche. Sorry We’re Closed argues that all monsters are deserving of love; indeed, there’s an argument to be made that James is the monster of his own design. In the context of the transmutative power of love in Sorry We’re Closed, perhaps Maria is the version of Mary that existed before she was forced to sacrifice the ‘you’ to become the lost wife that James seeks.

James Sunderland is the architect of horror, and his influence extends beyond the boundaries of Silent Hill. Sorry We’re Closed grapples with this, too. The Duchess has no short supply of victims, but none are as antagonistic to Michelle as the Massive Eyesore. This bodiless eyeball considers Michelle its sole rival for the Duchess’ ‘affections,’ which amount to the body horror inflicted upon it. James Sunderland is the Massive Eyesore, deconstructed to his extant, animal parts. He is seeing yet sightless, yearning for the sweet torture that can fill the loveless void within. Just as the Massive Eyesore regularly blocks Michelle’s progress through the underground, James Sunderland is the colossal figure that impedes the survival horror genre’s maturation.

“You will see me many, many, more times,” the Massive Eyesore promises Michelle, its gory tendrils spread across the expanse of its concrete prison, and we do. James Sunderland’s legacy sprawls across the genre’s landscape over a quarter of a century since Keiichiro Toyama laid down Silent Hill’s thematic and mechanical principles, and they persist in Sorry We’re Closed. This time, however, À La Mode invites the survival horror player, developer, and critic to look him in the eye, acknowledge his existence, and shoot him. Only then can we move beyond him.

Leave a Reply