UFO 50 is a hard game to talk about. Back in November, I hopped on a call with Jon Perry, one of the six developers who collaborated on the collection of 50 games, and found that discussing just one entry felt a little like attempting to discuss the entirety of a director’s filmography or every album a musician has ever recorded. It’s not that either of those tasks are impossible, but you can’t do it with any degree of depth.

That might sound like a strange analogy, but by Perry’s count, he worked as director or co-director on 17 of the collection’s 50 games. He contributed to more, but “this is a very collaborative project,” he says, “so those lines are all pretty blurry.”

Related

UFO 50’s Mooncat Makes Me Feel Like A Gaming Granny

UFO 50 includes 50 completely unique games, but only Mooncat makes me feel like a pensioner.

All 50 games were released across seven years in the 1980s, starting with 1982’s Barbuta and ending with 1989’s Cyber Owls. Unlike other compilations, though, the games in UFO 50 are credited to a developer that never existed. UFO Soft, and the LX-I, LX-II, and LX-III consoles the games were released on, are all fictional.

That means that the 50 games here — each of which is a fully-fledged experience, some taking dozens of hours to complete — were actually created by six people. The game was announced in 2017 with plans to launch the next year, but development ended up significantly swelling so, ironically, the real developers’ seven-year timeline ended up mirroring UFO Softs’ own.

UFO 50 Is Too Big For One Interview

You could write 50 articles about UFO 50, diving deep into how each of its games came to be. Perry says that feeling of being overwhelmed is intentional.

“Maybe that seems a bit odd now because it’s not like feeling ‘overwhelmed’ is normally a positive adjective you’re trying to create, but it was kind of the vibe we were going for,” he says. “You’re overwhelmed in the collection, you’re a little bit lost and so you have to find a strategy to navigate the wilderness… There’s not supposed to be a right way to do it. We think of it as an open-world video game itself, the larger collection.”

Related

Watching Someone Play Spelunky Is More Fun Than Actually Playing It

Spelunky is really hard and I’m awful at it, but that’s fine, because watching it is way more fun.

Instead of trying to wrap my arms around all that, I decided to focus on one of my favorites among the ones Perry directed: Bug Hunter. I’ve written about it before and compared it favorably to Subset Games’ beloved indie, Into the Breach. Like that tactics game, you take on buggy enemies on a small grid-based board, attempting to kill them all before they swarm you. But given UFO 50’s long development, Bug Hunter was actually playable in prototype form before Into the Breach was released in 2018.

“That game actually started life as a board game,” Perry says, noting that while UFO 50 entered development in late 2015, he had been building a tabletop take on the game that would eventually become Bug Hunter long before that.

Co-creator Derek Yu has said that the collection began as a way to navigate the changing tide around indie games, as the space became flooded and it was more difficult to stand out than it was in the late ’00s and early ’10s. That’s why many of the games that made it into UFO 50 began to take shape much earlier. In fact, Devilition (the tenth game to appear in the collection chronologically) is actually a remake of Diabolica, which Perry and Yu developed all the way back in the ’90s.

The Beginnings Of Bug Hunter

Bug Hunter ended up in UFO 50 because the tabletop gaming space was flooded, too — with games attempting to riff on the influential deck-builder Dominion. That version of Bug Hunter would have combined card-based play with a more traditional board game, but this design intention presented an obstacle for Perry.

“I didn’t really know how to sell that game because for one, I think just saying ‘deck-building’ in a pitch at that time would make publishers groan,” Perry says. Add in that the game had a grid board at a time when chess-like games were popular, and it was a perfect storm of mechanics publishers didn’t want to see. So it got scrapped. But that tabletop version of the game had many of the ideas Perry would later return to for Bug Hunter.

When development on UFO 50 started up, it seemed like a prime candidate for a digital makeover. Many of the ideas that ended up in the final version of Bug Hunter were there in its initial tabletop iteration. In the final game, you can push enemies into pits, movement can be a continuous walk (which facilitates those pushes) or a hop (which allows you to clear those pits), and energy cubes, which play a huge role in the final game, were there from the beginning.

Related

UFO 50’s Game Collection Is Stressing Me Out

UFO 50 offers so many good games, all at once, that it’s easy to get overwhelmed.

“The key insight of that game or the key mechanic that sort of makes it work is how the energy cubes are both your currency and they also can explode,” Perry says. “That fully existed in the board game pretty much exactly as [it is in] the video game. That was a big landmark moment. Before I had that, the game was okay. It was a little flat. You can move around and you attack people and so on. But once I added that, the whole game really started to sing a lot more.”

Battling Bugs Beats Battling Buds

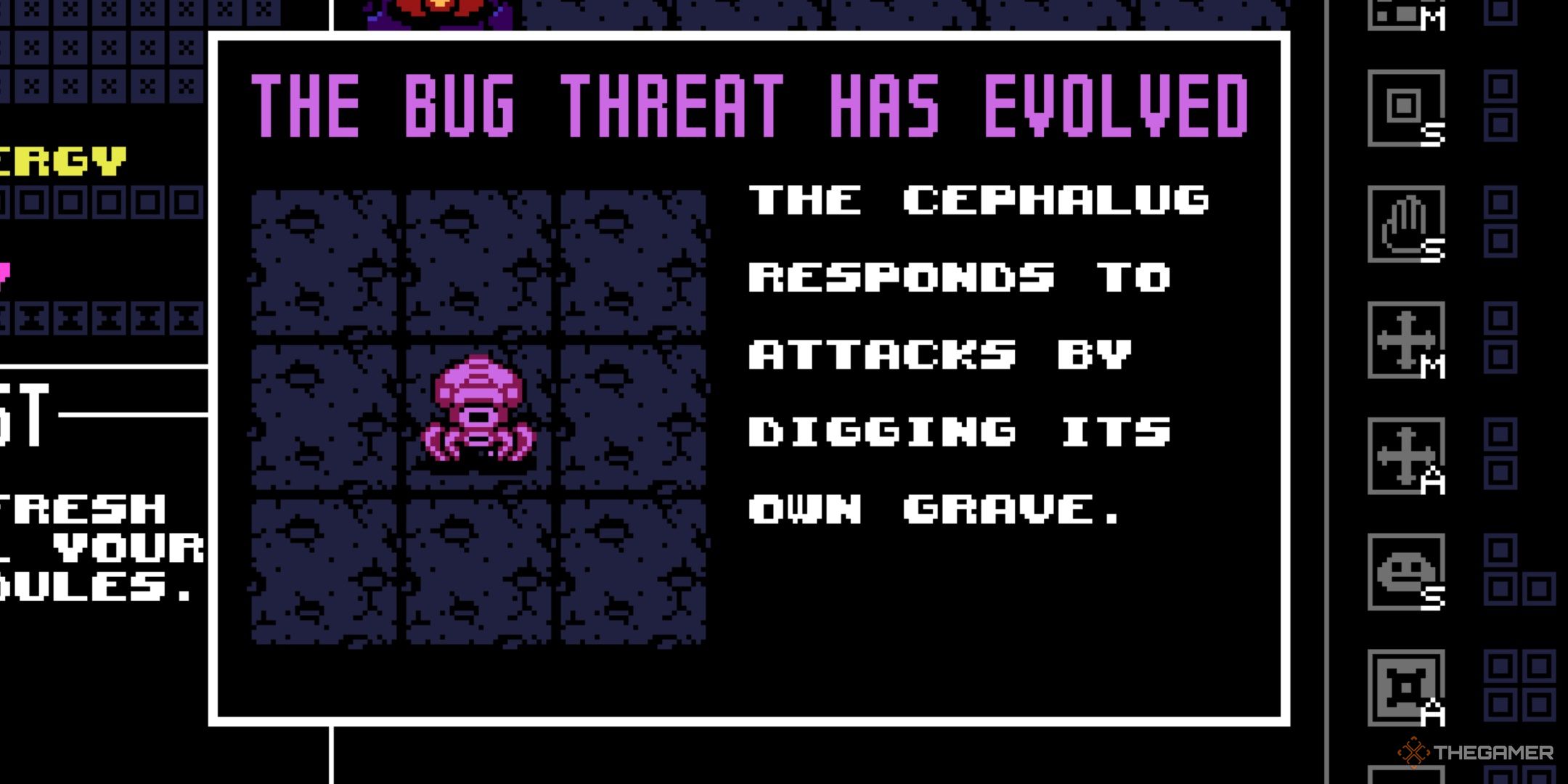

For my money, the most interesting aspect that emerged from the shift to a virtual space was the arrival of the bugs that you hunt (hence the name). Instead of taking on another human opponent, you were now up against a wide variety of insectoid aliens that would evolve until they take over the board unless you killed them first. This idea was originally meant for a different game in the collection, but Perry brought it over.

“If you’re playing a competitive deck builder game, I’m building up stronger and following some kind of advancement curve, but then also my opponent is, and so there’s that interesting dance that happens,” Perry says. “But how do you do that in a single player context? And so I had this idea that they should sort of have their own tech tree, their own path that they go down.

“And it has to be simpler than what the player does, right? They’re not buying individual modules and mashing them together, but they have these different evolutions. And I like the idea that they would sort of respond to what the player choices are, the way that your human opponent in a deck-builder responds, like they see you buy something and they’re like, ‘Oh, I better buy the counter to that.’

“So, the idea that it’s the bugs that you don’t kill that then evolve… there’s sort of a Darwinian logic to that that I find appealing.” In fact, it might take you a few hours to notice that the bugs never attack you. Their evolution, on its own, is the threat.

Bug Hunter is one of the best games in the collection (at least for this turn-based strategy fan), but in the end, it’s just one game among 50. The story of UFO 50 is big enough to fill a book — or, given that Yu once wrote a book on the making of his game, Spelunky, maybe 50 books — and that’s what makes it so overwhelming. Or, put another way, endlessly fascinating. We may never know everything that’s hiding in this wilderness.

18:47

Next

Which Indie Game Deserves To Be 2024’s Best

TheGamer’s video producer Cristian Macias talks with Eric Switzer about which indie game should win 2024’s Best Indie Game Award.

Leave a Reply