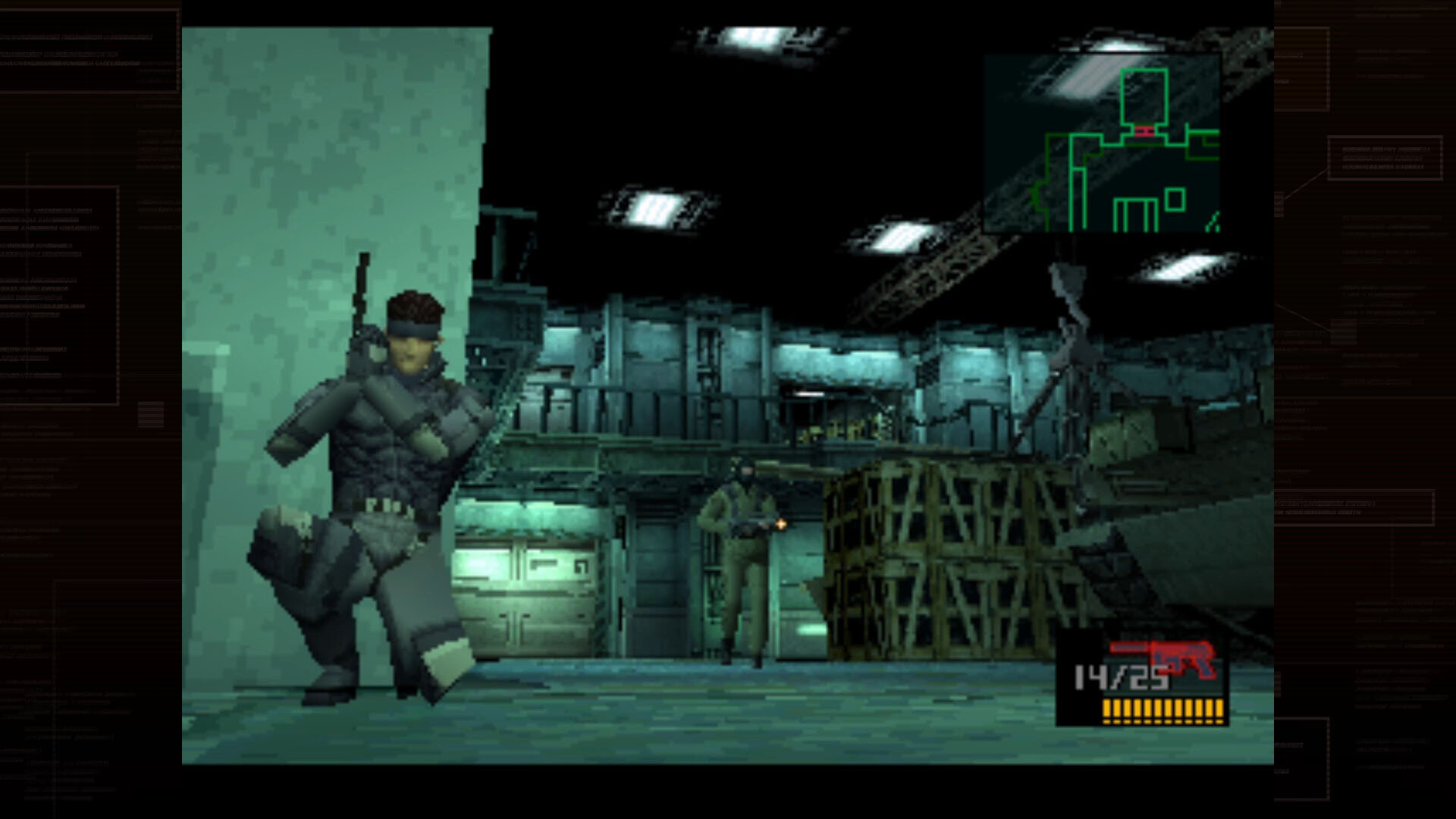

At the risk of giving the game an inflated Christly significance, it’s impossible to think back on a time when Metal Gear Solid didn’t exist. There is the now and the time Before Snake – and no in between. But that’s the interesting thing, for most of the gaming world Metal Gear Solid was kind of a sudden divine bolt of lightning from out of nowhere.

The Western world hadn’t really seen much of Hideo Kojima up until that point, what with a lot of his projects – however significant they are – sidelined onto doomed consoles or stuck without a localised version for years. Even the earlier Metal Gear games kind of just passed much of the world by without too much attention, and then, one day in 1997, everything changed. While footage of Metal Gear Solid had already been shown at Tokyo Game Show back in 1996 and earlier, it wasn’t until E3 the following year that gamers really got a glimpse of what would go on to be one of the PlayStation’s defining games. And from that point on, the hype was tangible.

“One thing you have to remember is that the first time the world saw this trailer, it was not just on some little TVs at the Konami booth,” says Richard Ham, who was the design lead on the PlayStation’s Syphon Filter. “This was on a gigantic jumbotron screen that towered over everything, I think it was the first time anything like that had ever happened at E3. And as I recall, every hour they would play that trailer, and for the entire convention this would become like appointment viewing – there’d be a huge crowd and so everyone would come and sit and watch. One thing I remember is being surrounded by a bunch of grizzled hardcore veterans screaming and whooping and hollering [as they] couldn’t believe what they were seeing.” The massive excitement surrounding that trailer even took Hideo Kojima by surprise, and naturally led Konami to push particularly hard on marketing MGS by the time it was released in 1998.

Over 12 million demo discs made it to players around the world, so there was a great deal of anticipation around what might well have felt like a debut game from Kojima, however inaccurate that was. “This is it. This is the surprise hit of 1998,” read a standfirst within CVG’s February 1998 issue. “You can have your Tekken and Resident Evil sequels, but if you’re after original software, watch this!”

Metal Gear Solid was featured in an article looking at the “Hot Games Of ’98!” and given a detailed rundown of what the game was all about, focussing on its stealth-heavy gameplay, the high-tech espionage story and its fully 3D environment. Curiously, the article also drew close attention to its cinematic qualities. “When playing the game you could be mistaken that you’re watching a movie,” it read. “That’s because the project’s director, Hideo Kojima, actually wanted to be a movie director before he got interested in games. This is evident when you see the movement of all the characters and how enemies react.”

Even before the game was released, the thing that stood out for most people wasn’t just the ‘thinking man’s shooter’ gameplay nor the top-tier 3D graphics, but instead it was the presentation of the game and its narrative. “It was so next-level, so many interesting camera angles for everything,” says Richard. “It felt so cinematic. Cinematic gameplay is something I was trying very, very hard to achieve with Syphon Filter, with camera locks and being a fan of John Woo and action cinema.” Syphon Filter, in the end, offered a “radically different kind of experience” than Metal Gear Solid, but that trailer for all its clever presentation and pseudo-real E3 glamour was a concerning moment for Richard and the team at Bend Studios. “I was despairing,” he says. “It looked like they were doing everything that we were trying to do, better.”

Sneaking mission

No one could deny that Kojima’s love of movies had an important impact on the way he directed his games, but to overlook the pacing of the game would be discrediting the famed creator – who these days gets some unfair treatment from gamers for his almost bookish attention to replicating a film-like experience in his modern games. But back on the original PlayStation, a game that was like a movie was something to strive for and that was something that Metal Gear Solid provided in a way no other game had before.

“In 1998, many people in the industry were talking about the convergence between movie and videogames,” says Francois Coulon, who was the creative director of Splinter Cell. “Probably because at that time, videogames were somehow jealous of the movie industry, feeling unfair not to be seen and perceived as an art as the movie industry could be. For a creative person trying to get videogames out of its cultural niche, seeing a sci-fi or heroic fantasy character in a two-minute-long, high-res cinematic before playing him as a ten-pixel high character for hours sounded totally wrong.”

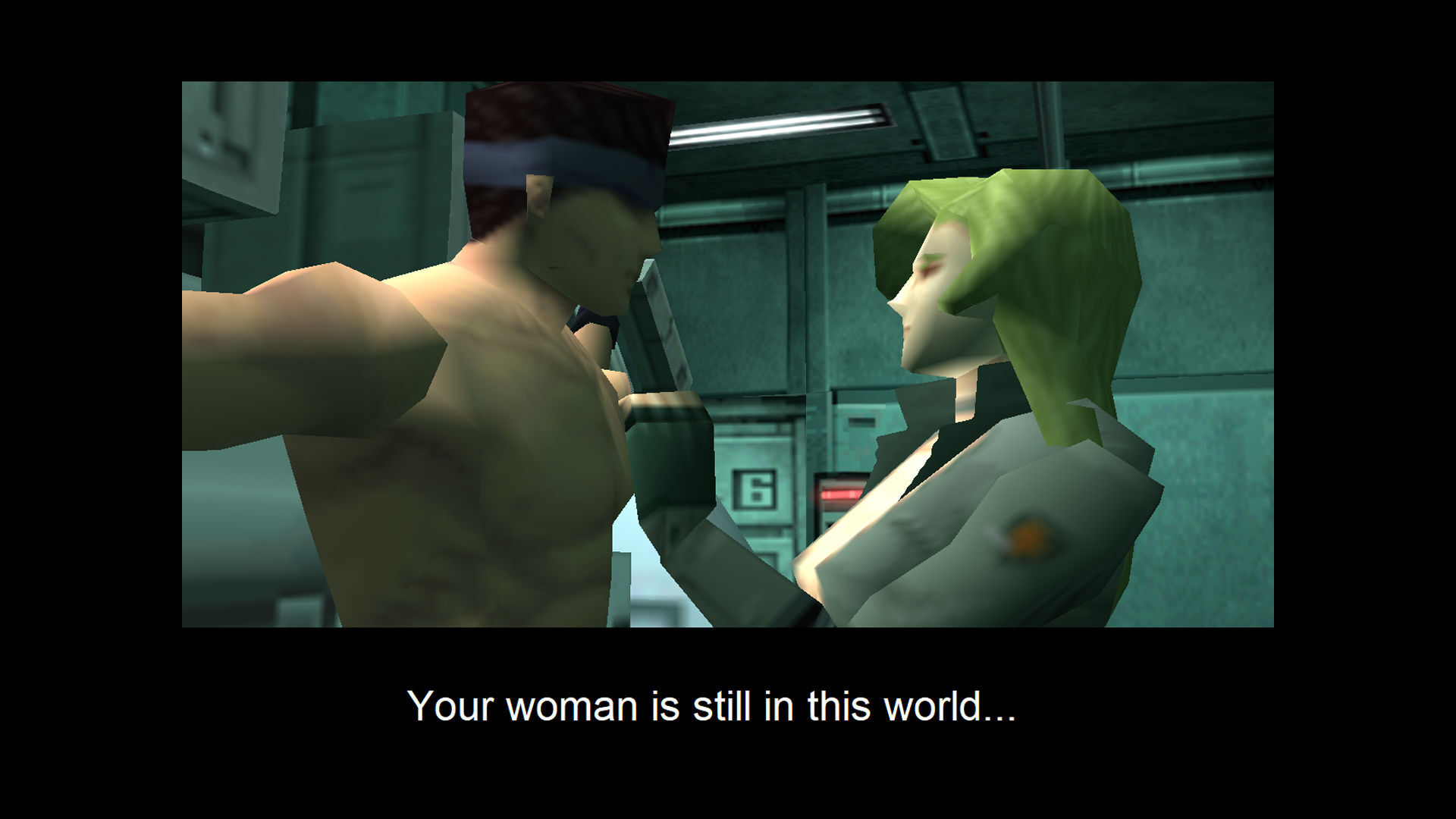

When Final Fantasy VII released on the PlayStation the year earlier, many had claimed that this was the best that videogames could look, but then the FMVs would end and you’d go right back to characters with cubic hands and three-pronged spikes for hair. Metal Gear Solid didn’t have that separation: everything that was shown in a cutscene was then playable in the next gameplay moment, and while the game might not have aged particularly well in the visuals department, it helped to build that immersion – that cinematic experience – by never separating those two distinct parts of the game.

“When you started MGS, you were launching a consistent visual experience,” says Francois, “with the opening cinematic played from the engine, with the same resolution as the game, in an almost realistic setting.” Francois adds that it wasn’t just about being consistent with the graphics, however, because MGS transitioned from cutscene to gameplay without loading screens, visual swaps or cues to let the player know that the gameplay was coming. The player was always playing. “Going further into the game, it provided a fully action movie-like experience. “Think of the sequence with the jeep in the tunnel, for example. This was going much further than all previous action games. And that was totally inspiring.”

Nowadays videogames are all agog about that ‘fully immersive’ experience, and never taking the player ‘out of the game.’ For some, exposition and narrative is one of the biggest ways of doing that. Ironically, Kojima’s approach to cutscenes grew to become outdated as developers learnt how to tell stories without ever wresting control from the player, but transitioning from quieter moments of character dialogue to full-blown gunfights with minimal separation between storytime and gameplay was arguably one of Metal Gear Solid’s biggest innovations. Even the long, highly wrought explanations that accompanied each cutscene felt novel at the time and it drew everyone in, gamers and developers alike.

Giving games a voice

Naturally all of these attempts to ape cinema would be for naught if there wasn’t a story worth telling, and in that sense Metal Gear Solid really stood out among the crowd. The industry was still trying to figure out strong narratives for a videogame, and while the PlayStation had already had some flashes of brilliance in this regard, MGS was on a whole new level. “I think the story itself is a very simple one,” says Jeremy Blaustein, who had worked on the original MGS as a translator at Konami. “Save the girl and save the day. It’s a classic spy story or an adventure story.” And he’s not wrong, the tale itself is not so complicated: a hardened war veteran is sent behind enemy lines without any sanctions to single-handedly stop a nuclear launch, it’s the plot of practically every Eighties action movie.

But it was the multiple layers to the story that made it enthralling, the unravelling of secrets and the way the distinct characters interacted with one another. “I think that the characters are very interesting and that is one of the most compelling aspects of it,” adds Jeremy. “I tried to give each character a unique voice and point of view after seeing how much Mr Kojima had worked to do the same thing in Japanese.”

Even as the series rolled on, memories of those more iconic conversations – the Master Miller reveal, for example – are tied to the overall experience of playing Metal Gear Solid, in part because it was a first time meeting these unique personalities, in part because of the piecemeal answering of hidden agendas and mysteries, but also very much because of their quippy dialogue and professional voice acting.

In fact, voice-over was just not a common practice at that point in time, less so to the standard that Konami put into the game. David Hayter became iconic as the voice of Solid Snake, and from there one of the PlayStation’s most recognisable characters. “I always viewed Solid Snake as an antihero,” says Jeremy. “That’s why in my mind the choice to make him sound like Clint Eastwood was obvious. I wanted him raspy and tired of war, and someone burned out. In my mind, the Clint Eastwood character fit the bill exactly.”

For all this talk of battle-weariness and nuclear war, however, let’s not forget that this was very much a game with a sense of humour. If there was a dramatic DARPA Chief death, it was very shortly countered by an equally tongue-in-cheek retort (and accommodating camera focus) about Meryl’s behind. “The characters are very cartoonish in a fun way,” says Jeremy, “but the setting is very realistic. It was my feeling that a realistic setting was necessary in order to maintain the feeling of authenticity that would allow for such cartoonish characters to be accepted without being laughed at.”

Genetically modified soldiers, nanomachines, cloaking devices, cybernetic ninjas and of course a stomping nuclear mech were just some of the far-flung pseudo sci-fi that Metal Gear Solid touched on, and that’s nothing considering the route that the series took in the long term. But all of it tied into fairly level-headed metaphors, and Kojima definitely had things to say about war, its impact on society and even its effects at an individual human level. “Do you think love can bloom even on the battlefield?” Dr Hal Emmeric, better known as Otacon, once posed to Snake in the game. It’s a memetic line and one that drew attention for its cheesiness, but it’s a good example of the varied threads that Kojima wanted to pull on with this cast of characters.

Cardboard box technology

“They lean into it, they find the funny, and it’s just an oddball mix of stuff.”

It all added a richness to the story, and that’s even before discussing its more supernatural elements: a wolf-mother sniper, a shamanistic raven-father toting a gatling gun, a telepathetic lunatic with a gas mask, all of it rounded out by a fistfight to the death between two cloned super soldiers. Read a string of words like that and you’d be forgiven for snorting at MGS, but its presentation, its cinematic narrative and the deftness with which the game handled its brevity directly alongside its more poignant topics made it one of the most compelling games on the PlayStation.

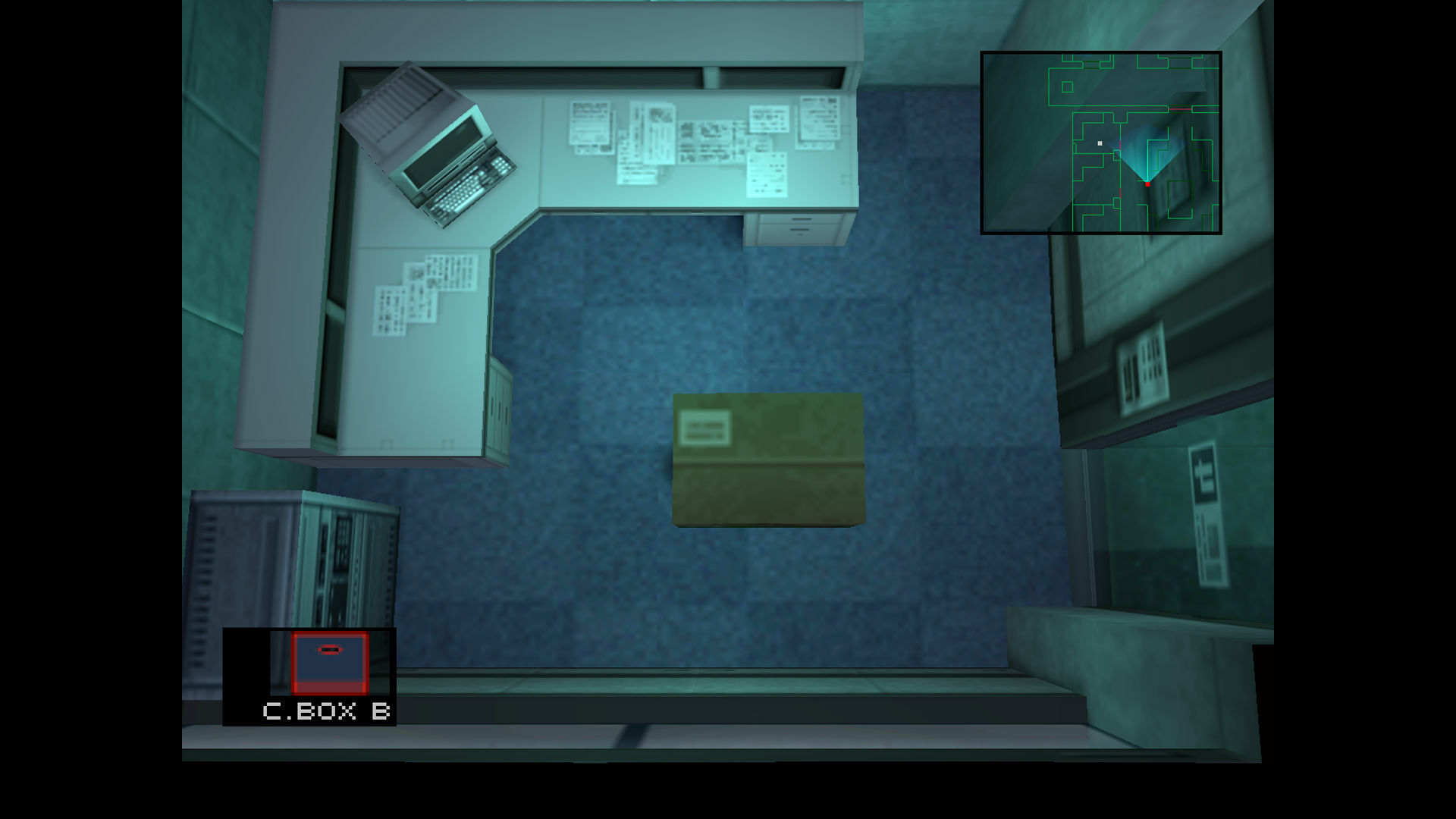

“Another thing that I really do think is incredibly important about Metal Gear is its absolutely odd, quirky sense of humour,” says Richard. “It’s the thing that they kept doubling down on that pretty much nobody else does. It’s just fundamentally weird that a cardboard box is your most powerful weapon in the game, that’s just strange, but they don’t care. They lean into it, they find the funny, and it’s just an oddball mix of stuff.”

How many games can say they have universally changed the appreciation of the humble cardboard box? It might be ridiculous to think of the world’s most famous infiltrator hiding in a cardboard box, but it perhaps highlights Metal Gear at its best, just as Richard suggests. It’s all very silly, at the heart of it, portrayed through an oh-so-sincere lens, so the idea of a cardboard box being the greatest asset for a sneaking mission just makes sense. The box became so iconic that it evolved just as much as the series did, while countless memes surfaced around it and the team at Konami found fun ways to include knowing in-jokes as the series grew over the years. But the gameplay wasn’t all military-grade packing solutions.

“Most people would say the story or setpieces [are the most inspiring parts of MGS], which I also love, but it is the refinement of the stealth gameplay that really sticks with me,” says Antonio Freyre, an indie developer whose most recent game is inspired by the Metal Gear series. “No other game has been able to get to that quality and elegant simplicity that the MGS games can do.”

Certainly as far as stealth gameplay goes, Metal Gear Solid is not overly complicated: watch the minimap, avoid those cones of vision and if you get spotted go and hide under a truck until everyone completely forgets you were there. It’s a permissive game, actually, Game Over (“SNAAAAAKKKE!”) simply drops you right back at the start of the room where you entered, there’s no traipsing back from your last save point or having to repeat a half hour of gameplay. But there are layers to it: footprints in the snow or the sounds of your steps on grated floors could give you away, smoking can help you spot infrared tripwires and there’s usually plenty of things to crawl under and hide. At the time players were astounded by the ability to rap on walls to intentionally draw a guard’s attention, luring them from their patrol routes to allow Snake to knock them out – or simply bypass them from a different perspective. “The first time I saw Metal Gear Solid was at a Blockbuster,” adds Antonio. “They had the demo to play in the store. I didn’t understand English back then so I had no clue what to do. I was stuck and couldn’t get past the [starting] Cavern area. Every time we went to Blockbuster, I’d try it again. I was captivated by this strange game where I had to hide.”

For the first time, players were asked to not fire a weapon – if they could help it – and instead use their wits to make it through a level. It was a completely new experience for many, not least since the earlier Metal Gear games had passed most by. “MGS showed us how stealth mechanics should be done,” says Francois, who especially points to the “clear rules” that are provided to the player to know exactly what is happening in the game and how to react to it. “It is a complete and consistent set of rules that set the way for any stealth game,” he adds. “Remove one of its elements and the experience will be dull, frustrating or ridiculous. MGS was perfectly executed in that regard. No frustration – you know when you lose and don’t blame the game for it.”

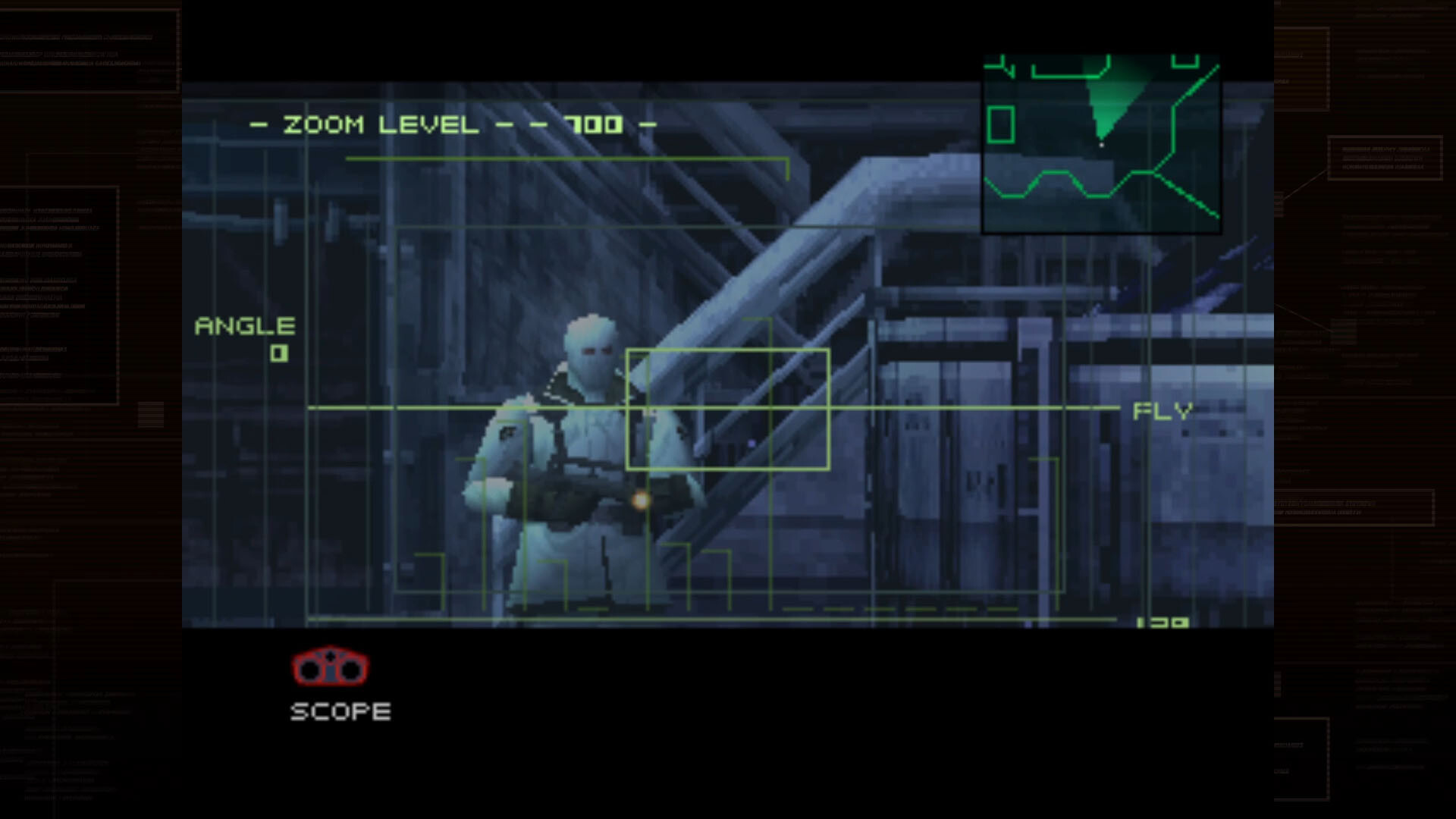

That’s not to say there weren’t moments of action, too. In fact, the pacing of Metal Gear Solid is something that gets overlooked, but with all those drawn-out Codec calls and quiet monitoring of patrol patterns, there was sense to add in moments of mandatory combat or set-piece battles. By 1998 the idea of a boss fight was already a long-worn concept, but even here Metal Gear Solid made sure to find new ways to keep these things fresh.

The most obvious is the fight with Psycho Mantis, where players could swap the controller to the second port to avoid the mind-controlling capabilities of the creepy psychowarrior, but practically all of Metal Gear Solid’s boss battles are memorable for one reason or another. Learning that bullets won’t win the day against Cyborg Ninja, a first-person sniper battle in a snowstorm with Sniper Wolf or even going mano a mano with a flipping Metal Gear REX are just some of those stellar boss battles that Metal Gear Solid conjured up, and they only ramped up with inventiveness and impact with each new release.

Ultimately, Metal Gear Solid was the game that put Kojima on the map for a generation of players, catapulting him to auteur status in a way that practically no other game director has been. Even now it feels very much like a game with a personality, with a very strict vision on what it is, what it wants to do and how it wants to do it. And while Kojima has since stepped away from the series, for more than two decades it defined his creative endeavours. “If the series has been so iconic for so long, it is simply because all the games were brilliant!” says Francois. “How many game series have been able to succeed over the years without slowly decreasing and repeating itself?”

Francois points to Kojima’s purity in game design, his high-level vision and a team able to execute it all to perfection as the reasons for the series’ long-lasting adoration. “It is hard for me to measure the impact of Mr Kojima alone vs Kojima and his team but, to be honest, it is not important. A creative lead in this industry is someone who can convey his vision to other team members so that they can also bring something to the creative table. I don’t know how Mr Kojima is managing his teams but the result speaks for itself!”

While there’s a deeper story behind the details of how Konami would later go on to handle Kojima, his team and the Metal Gear franchise as a whole, the fact is only a handful of games have had the immediate cultural impact that Metal Gear Solid was able to generate. It became one of the PlayStation’s most important releases, it snuck Tactical Espionage Action into a trigger-happy industry and it justified the relevance of gaming as a pastime to game developers and players desperate for videogames to become accepted as more than just toys for kids. If there was doubt, Metal Gear Solid proved gaming could be about so much more than squishing goomba’s and blasting cyberdemons and could, in fact, compete with movies.

Want to jump into some tactical espionage action? We’ve got our best Metal Gear games list right here for you!

Leave a Reply