When the tenth anniversary of the PlayStation rolled around on 3 December 2004, Sony was on top of the world. Its original machine had transformed the business, and the PlayStation 2 had only extended its market dominance. What’s more, the company was just days away from launching the PlayStation Portable, its first foray into the handheld console market – a field that had been dominated by Nintendo and its Game Boy family of consoles since 1989. Of course, Nintendo had seen off no shortage of pretenders to the throne over the prior 15 years, but Sony had already overthrown market leaders once and nobody with an ounce of sense was willing to downplay the potential for the company to do it again.

Sony announced the PSP – better known by its initialisation than its full name, even then – at E3 2003. Ken Kutaragi promised that the PSP would inhabit “a world where all kinds of entertainment, like games, music, movies are going to be fused together”, pitching it as “the Walkman of the 21st century”. The only piece of physical hardware shown was a prototype of the system’s proprietary storage media, the Universal Media Disc – a 60mm dual-layer optical disc contained in a plastic housing, offering a high storage capacity of 1.8GB. A concept image of the console itself later surfaced in November 2003 – a sleek, stylish black device with a look relatively similar to the final design, albeit with a totally flat d-pad and buttons and no apparent analogue input or shoulder buttons.

The PSP was officially unveiled at E3 2004, and it promised to do everything. As well as playing games, it would be your MP3 player and a machine to watch movies on, with prototype camera and keyboard accessories suggesting yet more functionality. The praise from the press was effusive. Edge described the machine as “an instant design classic some are already ranking alongside Apple’s iPod” and highlighted its impressive LCD display, quoting an attendee as saying, “You can see the screen from the other side of the fucking hall.” The games on show, including Ridge Racer, World Rally Championship and Dynasty Warriors “looked almost comparable, graphically, to their PS2 counterparts”. The magazine concluded that the real impact of the new hardware was “suddenly making portable gaming a viable proposition to those who’ve previously dismissed it”.

Nintendo officially revealed the PSP’s primary competitor, the DS, at E3 2004. The differences in approach became clear immediately, as Nintendo’s Reggie Fils-Aime told attendees, “While others plan to let you go a little faster down the same roads you have always travelled, Nintendo plans to take you down incredible avenues you’ve never seen before.” To that end, Nintendo’s machine offered a variety of quirky features. Tyler Sigman, who worked on both DS and PSP projects at Backbone Vancouver, remembers it well. “It was a really interesting time, because there was so much experimentation going on. DS had the novelty factor of the two screens and the touch and all that, but then PSP was this slick, higher-performance console.”

The big leagues

Chris Bourassa, who cofounded Red Hook Studios with Tyler after they had worked together at Backbone Vancouver, remembers just how exciting the PSP’s raw power was to developers as well as players. “I came off the N-Gage, so I was like, we’re in the big leagues now. I loved the PSP, because we could do so much more stuff.” It wasn’t just the processing power that was tantalising, either.

“The first time we got our hands on the PSP kits, we were immediately impressed by the size of the screen, the resolution, and the vibrant colours. It was a big step above the current handheld consoles (mainly the Game Boy Advance at the time),” says Rachid El Guerrab, then a lead programmer at Ready At Dawn. “The joysticks and controls brought it closer to the PlayStation DualShock, expanding the kinds of games we could imagine on the console. It represented a major advancement in mobile gaming, building on Sony’s legacy of innovation since the PlayStation.”

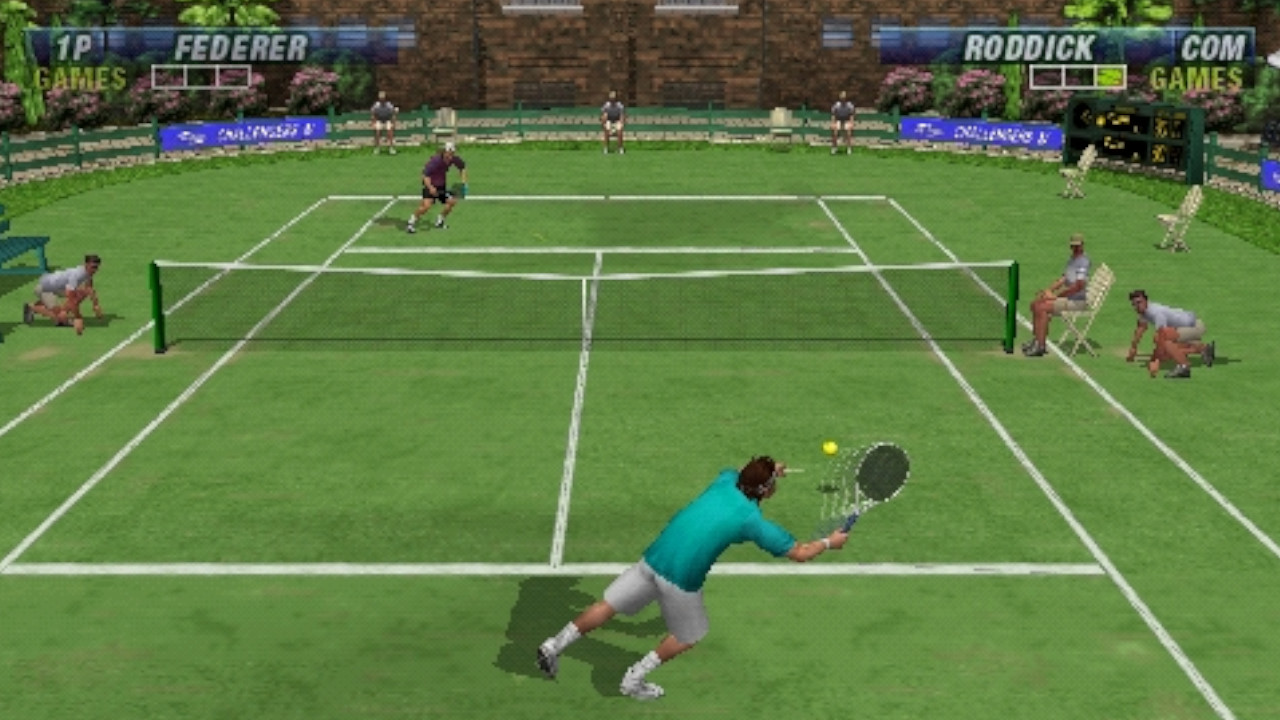

Those bold claims about the PSP approaching PS2 quality, though – surely they were somewhat hyperbolic? Phil Rankin of Sumo Digital was working on Virtua Tennis: World Tour at the time, which “ended up being a hybrid of the Dreamcast and PS2 versions of the game, with a number of unique features developed by us to add that unique ‘Sumo Twist'”, a situation necessitated by incomplete source archives.

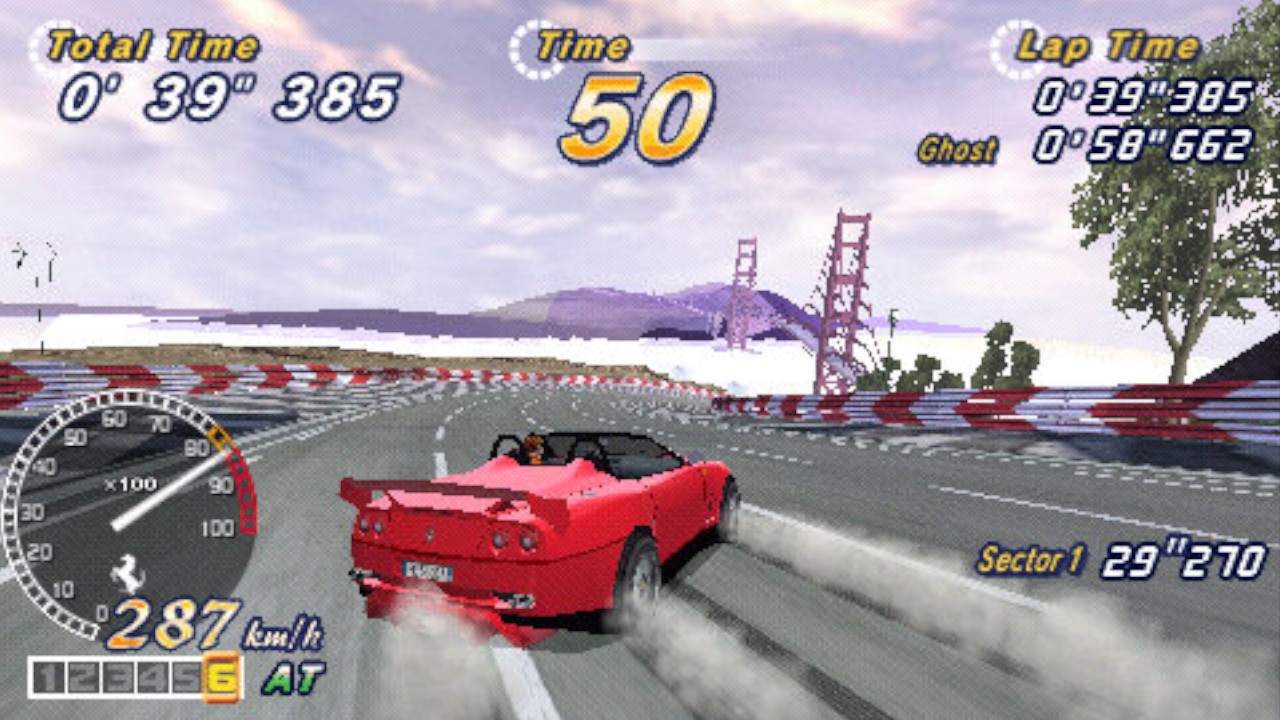

Steve Lycett, also of Sumo Digital, expands on the relationship between the systems. “For OutRun 2006 we effectively had three sets of assets, one for Xbox, a reduced one for PS2, then a further reduced one for PSP,” he recalls. “The screen size helped as fine detail got lost anyway and so we could afford to halve texture sizes. We also typically targeted 30fps too, and whilst the screen was much better than historic ones, you still had a slight motion blur and that helped smooth things out. We took a similar tack with the port of TOCA 2. In terms of CPU usage though we ran the core simulation at the same speed as PS2, so it had plenty of ‘torque’, you just needed to be careful graphically.”

All that power had to come with a caveat, surely? Edge noted that, “The only aspects to temper E3’s atmosphere of PSP excitement was talk of battery life and price,” and the former had certainly seen previous powerful handhelds fail.

An increasingly nervous Nintendo even used this as an attack line as the launch of the PSP drew closer – games™ reported that at a DS press event in November 2004, Reggie told those in attendance, “Those women at the Tokyo Game Show with those portable consoles strapped to them? What you didn’t see is that those women were having to go recharge the batteries every two hours. Nowhere will you find any mention of the… machine’s power life. And you have to wonder why.”

Battery power

As it happened, the PSP’s 1800 mAh battery proved adequate – but only because of careful development practices. For a start, Sony restricted the CPU to two-thirds of its full speed for the first few years of the console’s life. “On OutRun 2006, we’d politely asked if we could increase the CPU clock to hold a steady 30fps, but Sony declined on the ground of battery life,” says Steve.

The UMD drive was also a serious constraint on battery life, as Paul Hughes remembers from his work on the Lego games at Traveller’s Tales. “As the levels were coming off UMD we had to be clever about the disc layout in order to keep UMD seeks as infrequent as possible, as you wanted to reduce the times you span up and down the disc,” he tells us. “You needed to be pulling in as much data in one burst as was possible – you did this because spinning up the UMD drive put a drain on the battery and the longer the game could play on one charge, the better.”

That wasn’t the only way in which the UMD proved to be a source of pain, as Steve remembers from the development of Virtua Tennis: World Tour. “One problem that we discovered late was how slow the UMD drive was,” he explains. “Through development the game loaded from internal memory and the UMD emulation didn’t arrive until quite late. So it went from rapid loading before that to sloooow loading overnight. We spent a chunk of time speeding that up as best as we could. You could get test pressings on UMD, but these took time and due to the launch title pressure, I think we only did a couple.” Some early games really struggled with this, most infamously WWE Smackdown Vs Raw 2006, which could take almost two minutes just to load a wrestler’s ring-entrance scene.

Despite the development challenges, the software looked like it would deliver on the potential of the hardware. “I was still getting my head around writing for an actual magazine people were buying, so everything was exciting. I do remember going to a press event for the PSP launch and walking into a room full of branded standees which at the time felt like my first real behind-the-scenes moment for the industry,” says Leon Hurley, who was just getting accustomed to his new job, writing for Official PlayStation 2 Magazine as the console arrived. “When you saw games running on the PSP for the first time they didn’t have so much of a stripped back, handheld compromise feel to them.”

The PSP first arrived in Japan on 11 December 2004, and was greeted with great enthusiasm. Over 200,000 consoles were sold on that day alone – a figure slightly behind the 230,000 the DS achieved there, in part because Sony was constrained by supply issues. That enthusiasm was matched globally. In the USA, 600,000 PSPs were sold in the week after its launch on 24 March 2005, which left plenty of stock from the initial shipment of a million but was a little ahead of the Nintendo DS launch week figures of 500,000 four months earlier. Europe finally got the console on 1 September 2005, and the wait only seemed to make players more excited – 185,000 PSP consoles were sold in the UK alone on launch day, more than doubling the day one figure of 87,000 achieved by the DS and setting a record that would stand until the PlayStation 4 launched in 2013.

Small screen, big hitters

“Previously handheld consoles always felt they came with limitations.”

Great PSP games were present from day one. Ridge Racer was a potent demonstration of the console’s graphical capabilities, while games like Everybody’s Golf were perfectly suited to portable play. “Being able to play games such as WipEout alongside more traditional handheld titles, albeit very polished ones, like Lumines was a game changer,” says Phil. “Previously handheld consoles always felt they came with limitations; monochrome screens, low resolutions, limited controls etc.

The PSP was one of the first machines that had the hardware to allow you to play ‘proper console games’ on the go.” Other highlights of the early years include Tekken: Dark Resurrection, Grand Theft Auto: Liberty City Stories, Pursuit Force and LocoRoco. The PSP was also a great console for fans of classic games, playing host to a variety of fantastic retro compilations – and for all of the memes generated by the reveal of Ridge Racer at E3 2006, the addition of PlayStation games for download was great too.

Sony needed big name games on the console, but with the likes of Naughty Dog and Santa Monica Studio busy with other projects, it turned to Ready At Dawn to deliver. “Ready At Dawn treated the PSP as a first-class gaming machine rather than a handheld device, aiming to create big console games,” says Rachid El Guerrab, who worked there as lead programmer on Daxter and lead engine programmer on God Of War: Chains Of Olympus. “The team of veteran artists and programmers took the challenge seriously, producing full-scale extensions of successful franchises like Daxter and God Of War with high production values across story, design, art, sound design, music and engineering,” he continues.

“The one I probably remember being the most impressed by was weirdly Daxter,” says Leon. “Developer Ready At Dawn were obviously better known for whatever wizardry they pulled off with the two PSP God Of War games, but Daxter had a creativity that used the PSP really well.”

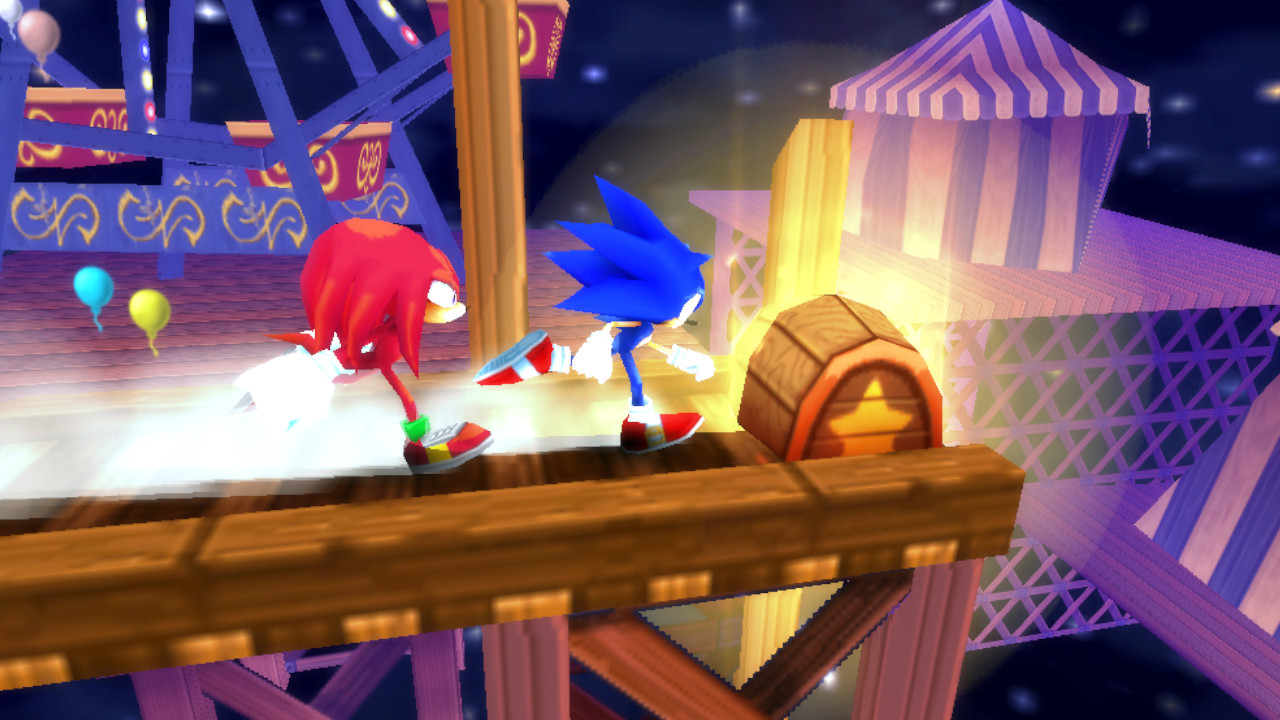

It wasn’t just Sony that was working with external studios to create bespoke PSP games, and those projects afforded developers precious opportunities to work on major franchises. “Sega was looking for a studio, and there was a request for proposals, so we put together a design for this game called Sonic Lightning, and they ended up choosing [Backbone Vancouver],” recalls Tyler, lead designer of what became Sonic Rivals. “That was all done on our own, without actually interfacing with Sonic Team, but once they chose us they quickly let us know that that’s not the game they wanted us to make.” The game Sega wanted was a 2.5D platform game with a strong racing element.

“We got some really cool, really interesting little sketches from them about how they think about how Sonic moves and how he should interact, and that stuff was really helpful. I think probably the coolest thing was to just get a glimpse into their workflow, because it felt a little bit closer to their creative wellspring,” recalls Chris, the game’s lead artist. However, the collaborative process wasn’t always straightforward.

“We did a lot of research into Sonic games and recorded footage of how they were laid out and how often certain features in a level would pop off,” Chris continues. “So we put a loop in, put some rings in there, and just make sure it feels good to run through that. And then we were told that not only should we not have rings in loops, but Sonic had never had rings in loops, in fact,” says Tyler, picking up the story. “I think the relationship was generally pretty positive. It was definitely just a learning experience,” Chris concludes.

Off the charts

While the games were good, Sony made some notable blunders when it came to marketing the PSP. The laughably inauthentic “All I Want For Xmas Is A PSP” marketing campaign ended in embarrassment, while a Dutch advert for the new white PSP resulted in accusations of racism. That wasn’t the only headache for Sony, as bugs in commercially released games – including the enormously popular Grand Theft Auto: Liberty City Stories – could be exploited to install hacked system software.

The emulation scene on the console consequently flourished, as did piracy of PSP games. “I did jailbreak my PSP very early on. I was running a SNES emulator and Doom natively and some other stuff,” Leon remembers. “Being able to run additional things on it was one of the system’s greatest strengths while it was still possible. I get why Sony had to stop it but it did feel like losing one of the console’s best features when it was gone.”

It wasn’t just the modding community unlocking the machine’s potential, though. Sony eventually relented on the issue of CPU speed and the first game to use the system at full power was God Of War: Chains Of Olympus in 2008. “For God Of War, our goal was to push the experience to a higher level, with improved graphics fidelity, larger levels, more NPCs, and complex interactions,” says Rachid. “Even with our experience with Daxter, achieving the desired quality at 30fps would not have been possible without utilising the full processor speed. If I remember correctly, our framerate would’ve been [roughly] 22fps without.”

“It’s easier to scale up than scale down.”

Despite starting strongly around the world, the PSP’s fortunes eventually diverged along regional lines – the picture was rosy in Japan, where the Monster Hunter games had become monster hits, but GfK-ChartTrack’s figures for the UK market showed that the PSP accounted for just 3.6% of game sales in January 2009. “Honestly, I think Sony took the eye off the ball with PSP – and in my opinion there was one reason for this – PS3,” says Jeb Mayers, then of Awesome Studios. “PS3 development was internally in dire straits by this point, and Sony were already playing catch-up with where they wanted to be. I could go into this a lot more, but suffice to say that after the successful launch of PSP all their attention then went into the PS3 and going on the offence/defence against Microsoft.”

Recognising this, Sony pledged to revitalise the PSP’s international fortunes in 2009. The platform holder announced a range of high-profile first-party games, including MotorStorm: Arctic Edge, Resistance: Retribution, LittleBigPlanet and Gran Turismo, with third-party support including Assassin’s Creed: Bloodlines, Rock Band Unplugged, Dissidia: Final Fantasy and Tekken 6. Keen-eyed readers will note that many of those names are more associated with the PS3 than the PS2, and the shift away from the older format did impact development. “At one point, after Lego Batman, we had to switch engines as the console engine had evolved to the point that it was too heavyweight for the handheld, so we switched to using the lightweight engine we used for the DS and amped it up for the PSP,” Paul recalls. “It’s easier to scale up than scale down.”

Mini moments

A new range of smaller, low-cost downloadable games called Minis was also announced, and the cost of development hardware was slashed by 80% to attract developers to create them. This brought some great games to the platform over the years, including Velocity, Canabalt and Pinball Fantasies. These were inspired by the success of low-cost iPhone apps, and intended to support a new piece of hardware: the PSP Go.

The new machine had an attractive form factor and 16GB of internal storage, but was also completely incompatible with existing memory cards, peripherals and even games, since it lacked a UMD drive. Dutch retailer Nedgame refused to stock the machine, citing its high price and the disadvantages of the download-only software model. Don McCabe, managing director of retail chain Chips, told GamesIndustry.biz that he was “99.9% sure it’s going to fail miserably”, and was ultimately proven right when the console was discontinued 18 months later.

In 2010, Sony failed to keep up its renewed international push. Popular games were reissued through a new £9.99 Essentials range, but high-profile new games were thin on the ground, with God Of War: Ghost Of Sparta, Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker and Kingdom Hearts: Birth By Sleep representing the cream of the crop. By the end of the year Bob McKenzie, GameStop’s senior vice president of merchandising and marketing, told Eurogamer, “If I were to pick a disappointment, the only thing would be looking at the number of titles that have launched on the PSP format compared to the prior year. I think Sony did a great job two years ago in terms of coming out with a pretty good line-up of PSP offerings and I didn’t see that breadth of titles this year. And it’s still pretty meaningful to consumers.”

Love, life, Vita

It wasn’t just retailers that were unhappy with the handling of the PSP by this point, as developers became increasingly vocal in their displeasure with the piracy situation on the console. Dylan Cuthbert of Q-Games had taken to Twitter in 2009, saying, “I don’t think we’ll port anything else to the PSP, we have to see how [PixelJunk Monsters Deluxe] does as there’s a lot of piracy. It was a shock to login to a PJMD chat room and hear them talking about how they were all playing ripped versions.” In 2010, Ready At Dawn’s creative director Ru Weerasuriya told VG247, “It’s getting to the point where it doesn’t make sense to make games on [the PSP], if the piracy keeps on increasing.” It was a tough message to hear from a developer that had achieved great things with the console.

The story was different in Japan, of course, where the release schedule was healthy and the system was buoyed by hits like God Eater. Through 2010 and into 2011, PSP fans elsewhere saw their hopes dashed as localised versions of exclusive games like Final Fantasy: Type-0 and the Yakuza spin-off Kurohyou: Ryu Ga Gotoku Shinshou failed to materialise. It felt like the console had more or less been abandoned as work proceeded on its successor, the PlayStation Vita – to the point that it was a surprise when Sony announced the new budget PSP Street model at Gamescom in the summer of 2011.

The Vita would launch in December of that year, and ended up as the international destination for Japanese PSP favourites like Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc. Though it lacked a UMD drive, the Vita was compatible with digital PSP games and downloadable releases continued until the release of Retro City Rampage DX in 2016.

The show goes on

Reporting on Sony’s decision to cease shipping PSP consoles in 2014, MCV noted that, “PSP spent much of its life being maligned as a failure,” based on the greater success of the DS – and like us, it considered that an “unfair assessment”. But the trade magazine still felt that “its legacy for many will be one of failure”, citing the decision to use UMDs, the push to sell movies on them and the disastrous PSP Go experiment. “All in all its biggest failure was perhaps its lack of killer IP,” the magazine concluded. “How many truly memorable PSP exclusive titles can you recall?” Sony had come to similar conclusions beforehand – in 2012, company representative John Koller told Gamasutra, “The issue that happened with PSP is we got overrun with ports, it became very difficult for us to define what made PSP unique.”

“In retrospect I think that the PSP’s power actually counted against it in the end. All the big publishers tended to just take the cheapest route to making games for it – cut down PS2 titles with slightly worse controls. It meant the overall library didn’t have much of a draw, despite some real stand-out classics which were always PSP-specific games,” Leon reflects. “It didn’t help either that anything that did sell well got ported back to PS2 in the end – the GTA games for example. It meant that while the hardware was good and had all the potential to be a great console the library lacked any real weight.”

Despite that, the PSP remains memorable for those who embraced it, as Rachid tells us. “Before playing any games, the PSP was my first high-quality portable video player, superior to the DVD players that were popular at the time. I used it to watch the first videos of my newborn daughter in early 2005 and bought movies for overseas trips. I also enjoyed games like LocoRoco, Echochrome and Virtua Tennis, along with classics like Metal Gear Solid and Lumines.”

Sony shifted about 80 million PSP consoles – an impressive total, but Nintendo was able to broaden the market’s demographics with games like Dr Kawashima’s Brain Training and Nintendogs, and sold 154 million Nintendo DS consoles as a result. PSP owners bought 4.33 games per console sold, compared to 6.16 on the DS. Some have suggested that the PSP was a failure based on those numbers, but the truth is that the PSP’s hardware sales are comparable to those of the Game Boy Advance, and its software sales ratio falls between the Game Boy’s 4.22 and the GBA’s 4.63. If the PSP is a failure, it’s only in comparison to an exceptional competitor and the expectations created by Sony’s market-shaping prior successes.

Sony didn’t come close to breaking Nintendo’s dominance of the handheld market, nor did it revolutionise portable entertainment, its ambitions curtailed by the rise of the smartphone. But for all of its patchy support and some odd decisions, it did create a console that hosted plenty of memorable games, which are easy to experience today as PSP games are generally inexpensive. The PSP is due a nostalgic reappraisal and this 20th anniversary year seems like an opportune moment for it, so if you’ve previously missed Sony’s miniature marvel, now is the perfect time to dive in.

Bonus: Unmitigated Movie Disaster?

The ability to watch DVDs on the PS2 was a key part of that console’s massive success, so Sony desired to make films a central pillar of its strategy to turn the PSP into the “Walkman of the 21st century”. However, where the PS2 had latched onto an emerging industry standard, Sony’s plan with the PSP was to sell film and TV content on its proprietary Universal Media Disc format. Oddly, video was encoded using the H.264 format at 720×480 – far higher than the 480×272 resolution of the PSP’s LCD display. Special features seen in DVD releases were rarely included due to UMD’s smaller capacity of 1.8 GB.

The early push for the format was very aggressive – Sony gave away a million UMD copies of Spider-Man 2 in early system bundles, and non-gaming releases initially outnumbered games. By June 2005, Sony Pictures proudly reported that Resident Evil: Apocalypse and House Of Flying Daggers had both achieved 100,000 sales in the US, within only a couple of months. In the UK, new films were generally priced at around £20 at launch. Eurogamer reported that 100,000 UMD movies had been sold by the end of the console’s launch month in September 2005, to almost 250,000 PSP owners. Underworld was the most popular title with 7,487 sales, followed by The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy and xXx: The Next Level.

However, by March 2006 The Hollywood Reporter indicated a bleak future for UMD movies – major retailers such as Walmart were cutting shelf space and companies such as Universal and Paramount had dropped the format. Benjamin Feingold of Sony Pictures cited the inability to play UMD movies back on TV as a drawback, and also commented, “I think a lot of people are ripping content and sticking it onto the device rather than purchasing,” in reference to the ability to play video from the Memory Stick.

Despite those setbacks, Sony persisted with the format. In 2008, Sony Computer Entertainment America’s John Koller told Video Business that, “The biggest issue with UMD was the lack of creating for a targeted demo,” and explained that the company was now narrowly targeting a young male demographic and reducing the price of new releases to $10-15. Sony would also license titles from other publishers and handle all of the manufacturing, distribution and marketing itself. By this point, comedy films Wedding Crashers and Superbad were cited as the format’s best-selling films.

You may be surprised to know that over 1,700 movie titles were released on UMD during the format’s short life. They’re a rather diverse bunch, from contemporary blockbuster movies like Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy to Eighties favourites like RoboCop and The Terminator. More surprisingly, you’ll also find stand-up comedy from Peter Kay and Lee Evans and live music from Judas Priest and Depeche Mode. Adult releases were also available, the vast majority of them coming from the Japanese market. If you’re a collector, it’s a scene worth investigating as some UMD movies are now rather rare.

Want to jump into the PlayStation Portable? Check out our best PSP games list for suggestions on what to play first!

Leave a Reply