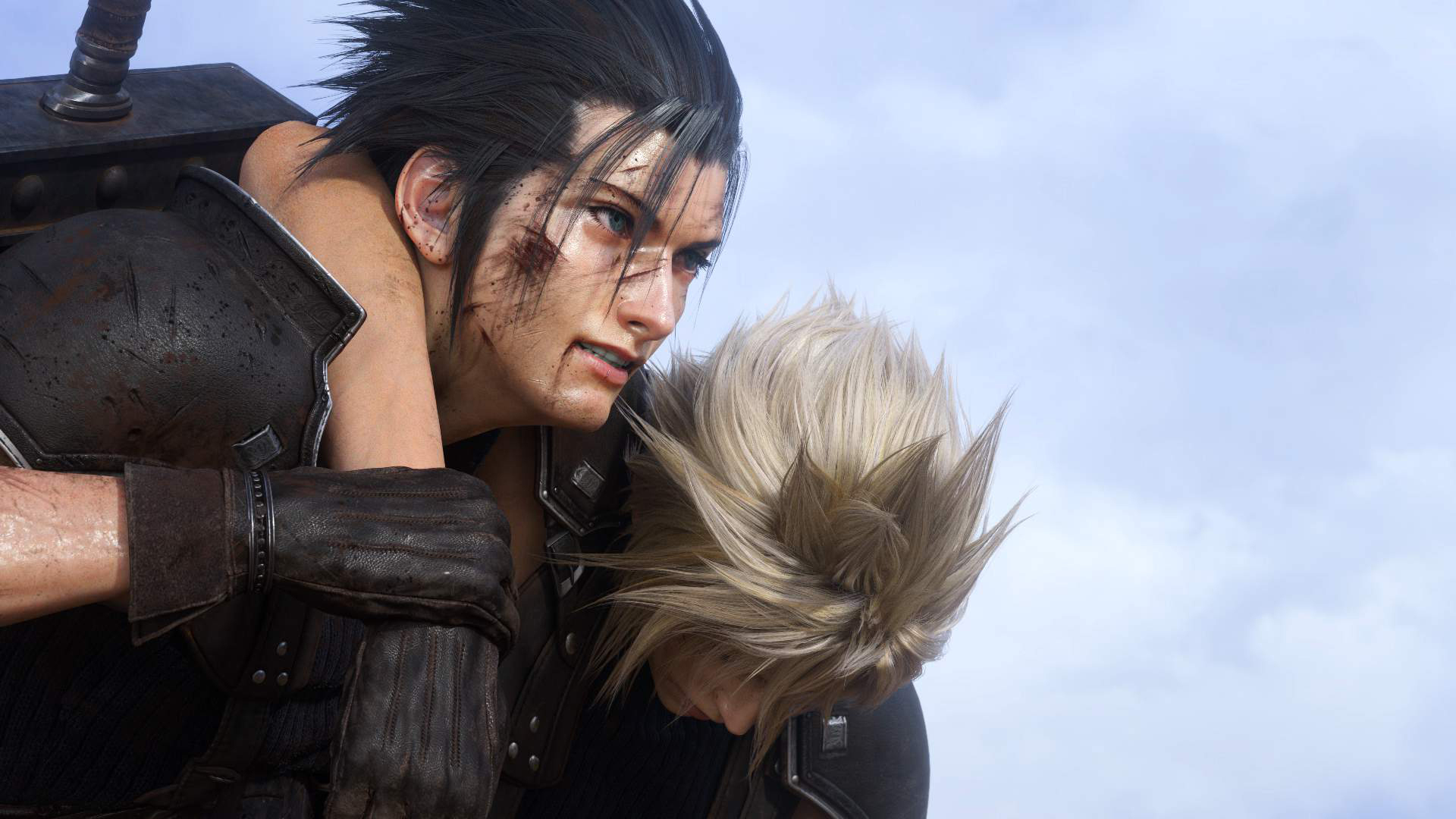

With The Game Awards out of the way, I’m awarding Final Fantasy 7 Rebirth my own personal Game of the Year. That’s thanks to its impressive reimagining of Final Fantasy 7’s open fields, iconic story, and memorable cast – along with its place in the series’ bigger picture. As the middle volume in a larger trilogy, it’s difficult for a title like Rebirth to hit new heights while simultaneously juggling the major plot twist of the first title’s ending with the will-it-or-won’t-it speculation about that moment from the original – one of the most famous scenes in gaming history.

Many middle volumes struggle to maintain momentum as they move through the tricky traditional structure of middle acts. Everything sucks at the start, and it’s gonna get worse before the end. But, the best of them? The Empire Strikes Backs and The Two Towers? Those ones handle this beautifully by turning large scale conflicts into personal ones, and that’s exactly what Rebirth does as it expands the relatively narrow world from 2020’s Final Fantasy 7 Remake into a pseudo-open world, while closely examining the mental and emotional toll of saving the world. It’s intensely personal in a way that exceeds Rebirth, and even the original, giving life and purpose to Cloud’s companions in a way that’s only abstractly hinted at in the 1997 original.

For many fans – me included – it’s also a reminder of what Final Fantasy used to be when it was less concerned with appealing to a wide mainstream audience, instead designed first and foremost to appease existing fans and the creators themselves.

Party up

For almost two decades, from its initial release in 1987 to 2000’s Final Fantasy 4, the series had a very distinct identity, but since the release of Final Fantasy 5, which threw away most of what had come before—introducing a new combat system, world design, plot structure, and even UI/font—the series has struggled to really convince fans what it means to be a Final Fantasy game.

“Final Fantasy is not what it once was, culturally, but it can still be there from a quality perspective,” PC Gamer’s Marc Normandin argued in a feature that catalyzed my thoughts on the problematic fluidity of Final Fantasy’s modern identity. “Square needs to take a lesson from the thriving franchises around it and figure out just what Final Fantasy is supposed to be, like Falcom has with Trails, like Sega has with Like a Dragon. Each of their sequels push their respective envelopes without betraying expectations.”

I see a series that’s struggling to understand its identity – a series that was mired by doldrums for nearly a decade as Square Enix‘s ambitious, but ultimately fatal, Fabula Nova Crystallis series floundered, eventually culminating in a clearly rushed release for Final Fantasy 15. Then came 16, a return to the series’s epic fantasy storytelling roots, but a vast departure gameplay-wise, sandwiched between two beloved entries in the Final Fantasy 7 Remake trilogy, further throwing the series’ identity in flux. While it felt more technically polished than 14, it lacked the mechanical depth and more methodical RPG elements that drew many fans to the series in the first place, while also lacking the sophistication of the character action games it drew inspiration from – trying to appeal to everyone, but satisfying few.

Final Fantasy 16 and Rebirth paint a dichotomous image of a series in flux, both at war and in conversation with its past. But to find its future, Final Fantasy can look to its past for all the answers.

Revolution or evolution?

Best of the best

Finished Rebirth? Here are the 10 best Final Fantasy games of all-time that you should consider playing next

Modern Final Fantasy has an apocryphal reputation for redefining itself entirely with each new entry –but this wasn’t actually the case for most of the series dating back to its second entry. Rather than revolution – as we see nowadays – Final Fantasy experimented in ways that were more evolutionary by taking the base successes of the previous titles and tweaking or building on them, rather than throwing everything out and starting from scratch.

In a 1990 interview, series creator Hironobu Sakaguchi said, “It feels weird to talk about it this way, but when you compare Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy, in a lot of ways I think it’s easier to imagine how the Final Fantasy game will be, you know?” If you asked a group of fans what they expect from the next Dragon Quest, he continued, you’d get a variety of answers. “But with Final Fantasy we’ve always put an emphasis on strong visuals.”

From its inception, Sakaguchi saw Final Fantasy as an opportunity to experiment, but his ultimate goals were to create gaming experiences that rivaled the narrative and visual splendor of film. Nowadays, most fans would consider Dragon Quest to be far more same-y from title to title compared to Final Fantasy – but from their inception both series had specific structural and technological underpinnings that helped them feel cohesive across releases.

In a separate interview that same year, Sakaguchi further explained his philosophy for change and evolution in the series:

“In terms of the gameplay systems, I want FF4 to be a completely different game. That’s one of the staples of the Final Fantasy series, that we change things up every game. FF3’s job system was popular, but that doesn’t mean we want to make a sequel that upgrades that with like 50 jobs or something. We don’t like doing ‘upgrade version’ style sequels. Our staff would become completely bored if we had to work like that.

“The ‘Final Fantasy’ title is a general title for this world that is more-or-less united by things like the crystals and the shared items and magic. That’s why we don’t mind changing up the game systems every time. Sequels that only change the story and nothing else are boring, right? I hope players will enjoy experiencing a new Final Fantasy world each game.”

This stands out, however, because comparing Final Fantasy 3 to 4, it’s easy to see Sakaguchi’s increased emphasis on story and drama, but the underlying game systems are functionally similar. FF4 replaces FF3’s job system with a more linear character progression system and a far more complex and melodramatic plot. Final Fantasy 5 improved upon 3’s job system, and retained its more straightforward plot. Final Fantasy 6 took 4’s narrative success and bifurcated it into dozens of smaller, interconnected stories. And, well, you get the point.

This style of iterative experimentation essentially defined the series for its first nine entries. Each game experimented in its own way, but not so dramatically that it changed the overall experience very much. And the presiding feeling with each title is that you were playing something that felt like a piece of a cohesive whole. You explored a world, you got into random battles, you waited for your ATB meter to charge, and then you selected your action from a menu that barely changed from the first title to the sixth. They felt like Final Fantasy.

By relying on existing frameworks and series traditions, Square Enix was able to release six mainline Final Fantasy games between 1991 and 2000. Final Fantasy 10, which followed just a year later, marked the series first major departure from that structure, and it was followed by an MMORPG (Final Fantasy 6), and two of the series most divisive and troubled entries (Final Fantasy 7 and 13), both of which experienced significant delays. Eight years separated 10 and 13, and it would be another seven years before 15. Perhaps not surprisingly, this started almost immediately after Sakaguchi left Square Enix, handing the series off to other creators.

With the increasing costs and timelines associated with AAA development – especially for series like Final Fantasy that have focused on being top-tier cinematic experiences from the beginning – it doesn’t seem like a stretch to suggest that the opportunity cost of Square Enix throwing everything out with the bathwater when it starts a new Final Fantasy title from scratch has hurt the series’s reputation as a genre leader.

So, what can Final Fantasy learn from its past success to return to form?

Back to the future

Starting with a blank drawing board can offer wild, inventive outcomes, but it also comes at the increased risk of dead ends, spiraling scope creep, and a lack of prior lessons learned

With Final Fantasy 7 Rebirth’s successful reimagining of the series’ golden age, I’d like to see Square Enix return entirely to the series’ origins to help define its future. Experimentation within Final Fantasy used to be iterative and focused, rather than wholesale reinvention with each new title. Final Fantasy 7 Rebirth’s beautiful open world exploration, vibrant towns and natural landscape is a template for new worlds and stories. Its combat is a perfect blend of the popular ATB battles found in Final Fantasy 4 through 9, with the freneticism we’re told is essential for mainstream success these days – though I’m skeptical, given the recent success of games like Metaphor: ReFantazio and Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth.

Take this obviously successful and well-liked template and use it for the next mainline Final Fantasy title – exactly as Square’s going to do with the third and final volume in the Remake trilogy. Iterate and improve existing success, maybe even over a couple of mainline titles released on a quicker and more consistent schedule, and lean into the creativity awarded by constraint. Starting with a blank drawing board can offer wild, inventive outcomes, but it also comes at the increased risk of dead ends, spiraling scope creep, and a lack of prior lessons learned.

Final Fantasy 7 Rebirth is the best game of the year because it took a well understood success – the original’s explosive middle act – and worked with established systems, instead of trying to redefine everything from the get go. It was an experienced team, who’d worked together for a long time on Remake, using familiar tools, workflows, and ideas, and nailing the iteration. This, just like Final Fantasy games of the past, could be just the recipe for the series’ return to being an undisputed leader in the genre it helped popularize.

Final Fantasy 7 Rebirth was just one of the titles we chose for our best games of 2024 ranking

Leave a Reply