The greatest trick that Planescape Torment pulled is disguising its verbosity – an eye-watering script of 800,000 words – by relying on, and then swiftly subverting conventions. As an immortal known as The Nameless One, you wake up on a mortuary slab with no memory of how you came to be there. Typically this would be an opportunity for exposition, a perfect moment to explain to the player, via a cast of characters, about their circumstances, while allowing them to project their own identities onto a blank slate. But then a talking, floating skull points out that your body is heavily scarred, including one tattoo on your back with instructions on discovering your past lives. And it turns out the tale behind Planescape Torment is a more personal one. It’s about unravelling The Nameless One’s lifetimes of history, resonant with memories, rather than an altruistic, heroic odyssey to right a cosmic wrong.

And this is merely one example. These tricks are artful sleights of hand, with developer Black Isle Studios reforming somewhat established structures in RPGs with Planescape Torment. Take character creation, for instance; you begin by assigning points to your stats, but you won’t get to choose your character class. That’s because by default you’re a fighter, and only by meeting certain characters or completing specific quests can you embody the thief or mage class. According to the game’s design document, this is a deliberate decision by its developers, who wanted the player’s actions to define their character, rather than allowing them to choose a class from a dropdown list.

At the same time, Wisdom and Charisma were among the more important attributes, given how ludicrously janky combat encounters are. Rather than bashing skulls together, negotiating and even manipulating your enemies (and friends) may reward you with more experience points instead. The trappings of what makes a power fantasy has been demolished; banishing lesser beings with a mere flick of your finger isn’t likely to happen. So while you may chance upon a combat buff or a crudely doodled tattoo (Planescape Torment’s equivalent of stats-boosting equipment), the game undermines the importance of hoarding such supplies. Instead, it’s the possibility of unlocking more dialogue options and narrative branches that seems more appealing. Why eviscerate a zombie when you can talk to it instead? Planescape Torment was the anti-Diablo of the 90s.

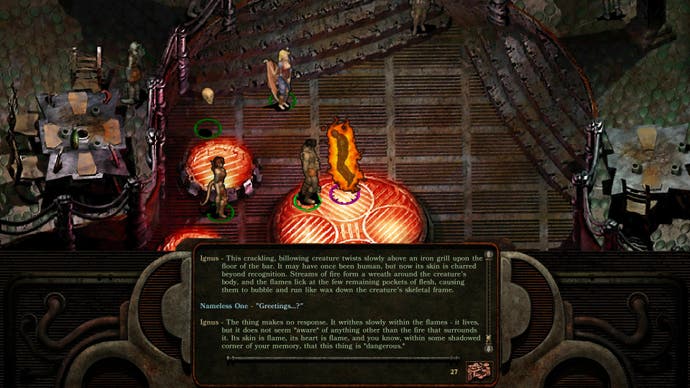

That said, even among the pantheon of the era’s RPGs such as Baldur’s Gate, Fallout, Chrono Trigger, and the Elder Scrolls series, Planescape Torment remains an oddity: largely described as a “commercial disappointment”, and too offbeat, abrasive and self-indulgent to appeal to RPG enthusiasts when it was released. Unlike the adrenaline and strategising in these games, Planescape Torment eschewed fluid, immersive combat in favour of inscribing every scenario with nearly imposing walls of text and dialogue. The latter would have been tedious to plough through, if not for its writers’ ability to capture the minutiae of every interaction in abundantly gritty detail. One inhabitant of Sigil is portrayed as a presence with an overwhelming sense of eternity, “almost as if this man were a shell surrounding an illimitable expanse”. Another was a strange tale of a githzerai Ach’ali, who was said to have asked so many “useless and unfocused questions” that “her isle of matter dissolved around her, and she drowned”. Fortunately, Planescape Torment never gets any less bizarre.

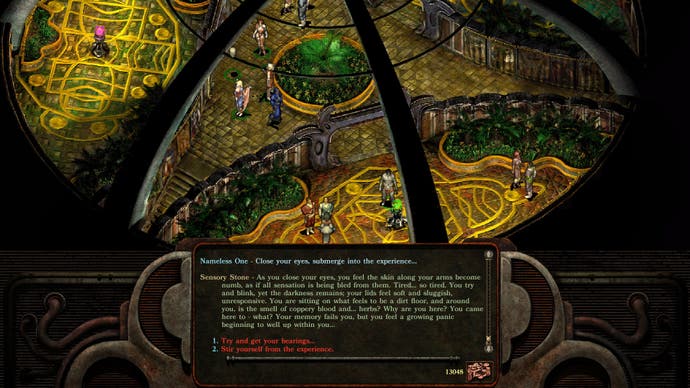

And given that the game is set in the obscure Planescape campaign from Dungeons & Dragons, Planescape Torment featured none of the Tolkein races, the likes of elves, dwarves or goblins that were so commonly featured in other high fantasy RPGs. Instead, various humanoids races live in squalor, with zombies, wererats and fiends roaming in the underbelly and outskirts of the city of Sigil, and where beliefs can reshape worlds and bend reality.

Sigil, in particular, is deliberately disorienting and peculiar. Ever-changing streets shift to the whims of its inscrutable ruler, the ominously-named Lady of Pain. It’s where alleys whisper secrets and heave with agony. It’s where myriad interplanar portals that lead to several realities are hidden in plain sight. It’s where anecdotes abound, of unwary denizens from other planes who have been ensnared in Sigil against their will, as they accidentally stumble into the city through unmarked portals.

The streets are a mix of musky detritus and derelict buildings hastily constructed over one another, with towering spikes and jagged architecture lining its boundaries. So while Sigil is a thoroughly unwelcoming city, it’s also wonderfully fascinating. Every landmark carries a personality that’s reminiscent of the wretched lives of its denizens you encounter along the way. Even decades later, there hasn’t been another RPG setting like that of Planescape Torment, where even debauchery is engraved into its very grounds and walls, its spaces infested with a creeping sense of misery.

But discussing the game’s grotesque appeal would be remiss without bringing up The Nameless One’s companions. They’re a cast of compelling, yet eternally ill-fated individuals whose biggest folly was the sheer misfortune of running into The Nameless One. Morte, the jabbering floating skull who you first met at the mortuary, yaks so much that his insults (“Flies wouldn’t even rest on your carcass!”) can infuriate enemies into suffering penalties to their damage. But you’ll soon learn that his offer to guide you along your amnesiac journey is not a magnanimous one, but one borne out of guilt.

There’s also Fall-From-Grace, who’s a mixed bag of contradictions: a chaste succubus who likes engaging in intellectual conversations so much that she became a proprietress of a brothel – one that specialises in stimulating, intelligent experiences, rather than physical pleasures. There’s Dak’kon, a fiercely loyal githzerai who’s sworn to protecting The Nameless One for life, but also tormented by his immortality. There’s Ignus, a pyromaniacal mage who’s the centerpiece of a little establishment known as the Smoldering Corpse Bar, and who you can recruit if you can douse his eternal flame. And there’s also a walking suit of armour, Vhailor, who’s dedicated to meting out justice even beyond his death. All of them are tied to The Nameless One’s wretched fate in some way, and their backstories are essentially a chronicle of magnificent catastrophies. More so if you decide to steer the current incarnation of The Nameless One towards committing unspeakable evils.

And then there’s the question of death: the one device that Planescape Torment is perhaps most remembered for. The ability to live forever – to be killed but without being killed – has afflicted The Nameless One with the inability to hold on to any memories, and this has repercussions beyond what was immediately obvious. As a player, your death doesn’t spell the end of the game, with you merely materialising in the mortuary if you had suffered fatal injuries. This can, at times, be one way to help you out of tight spots, such as reentering certain areas of the game (fun fact: the mortuary can only be accessed by the dead). But more than that, this transformed the purpose of death as a mechanic. Your death is referenced and remembered by others, who sometimes discuss the nature of your immortality. Dying is no longer a fail state; it has become another means of interacting with the universe and its infinite perils.

Planescape Torment is genre-defining not only by virtue of its enthralling scenes, but also its horrific revelations, imparted through its text and narrative devices: that the past incarnations of The Nameless One might have been cruel in the name of pragmatism, that your deaths have doomed more than just a village of souls, and that the unforgivable nature of your crimes may have, ironically, doomed you to a lifetime of immortality. Its legacy is reflected in the fervent community discussions that are still going on decades after its release, and the influence it continues to have on modern games, such as the critically acclaimed Disco Elysium, which builds on the Planescape Torment’s love for the written word to also suffuse its world with paragraphs of velvety text.

That said, Planescape Torment hasn’t aged that well; it’s a 25-year-old game after all, beset by resolution issues, unintuitive UI and tedious, repetitive battles. But these feel like largely technical concerns – issues that are bound to show up as technology advances – with these largely polished with the release of an Enhanced Edition in 2017. Despite the years, the game’s tragic tale of torment, violence and mortality has remained as salient and invigorating as ever. I’m guessing that in another 25 years, it’s these traits that would stay unsullied by the passage of time.

fbq('init', '560747571485047');

fbq('track', 'PageView'); window.facebookPixelsDone = true;

window.dispatchEvent(new Event('BrockmanFacebookPixelsEnabled')); }

window.addEventListener('BrockmanTargetingCookiesAllowed', appendFacebookPixels);

Leave a Reply