Naiad offers real pleasures and real frustrations – but always with a purpose in mind.

There’s a moment when I’m swimming that I can’t get over. I’m about to start the front crawl. Feet up against the side of the pool, arms pointed forward, face in, kick out, and then…

Naiad review

…Then I’m suddenly entirely alone in a world of purest blue. That blue! The matte blue of the pool’s floor, coming to me through a few feet of water. With my head down, I can feel the surface of the water arc up over my scalp and shoulders. I have a breath to let out before I start to think about arms or legs, but for now I feel like I could stay in this place forever.

This is a feeling that Naiad, a new game about wild swimming, absolutely nails. There’s no polite pool wall to kick against, and Naiad themselves does a lot of backstroke and a lot of dolphin kicks rather than much in the way of front crawl, but that sense of being in the water, being in the water with a purpose, a sense of belonging, that sense that your skin and the skin of the water are working together to move you along? Naiad absolutely delivers.

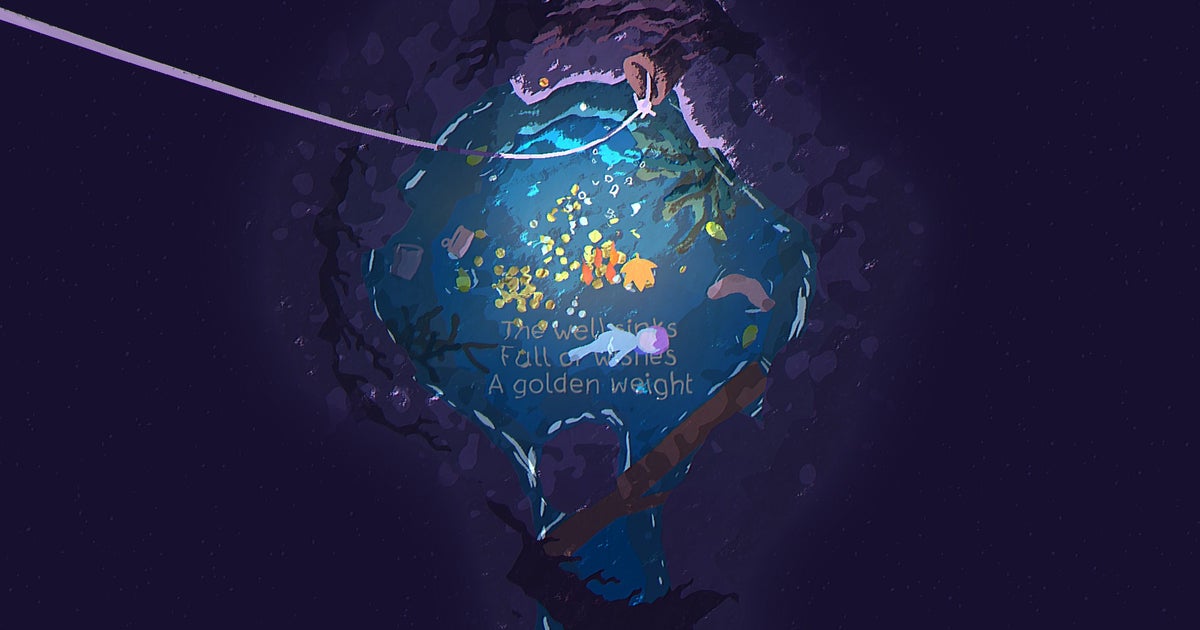

Naiad’s a fascinating game, but it was such a thrill, such a watery delight at first that it took me a while to notice this. For the first few levels, it sets out a simple framework. Viewed from the top down, you move around a selection of lakes and little rivers, encountering wildlife, interacting with the things around you in a variety of toylike ways. You can sing to attract animals, so you do a lot of collecting ducklings and returning them to their parent. You can gather frogs behind you and land them on their lilly pads. You can sing to make the flowers grow, or to move bees back to their hives. You’re a sort of nymph, a spirit of the river itself, and in Naiad, particularly in the opening sections, the river is something that takes things home.

It’s beautiful stuff, with perhaps my favourite video game water since Super Mario Sunshine. You see the glitter on the surface, and the ripples where it meets the shoreline, and you see the way that branches and flowers settle on it and bob around. But you properly feel its invisible forces. You feel the current as something you negotiate as you use the simple controls: one stick to steer, another to pull off a dash, another to take you under the surface to navigate certain obstacles.

There’s such a pleasure in textures here. The wildlife on the surface often looks like it’s made of paper: paper bushes, paper grass, paper birds that you’ve helped find their perches in paper trees. More complex animals are made of different parts, so a bear feels like a negotiation between his arms and legs and snouts. And the water itself? Nowhere and everywhere, revealed in a pearly sheen in some sections where you need to know specific currents, hinted at in trails of bubbles elsewhere. At the end of each level the entire screen dissolves in particles like wet sand before scattering. Naiad is a game to immerse yourself in.

Funny talking about sand, because around the two-hour mark, if you asked me what Naiad was, I’d say it was a very gentle sandbox. You get from A to B in the early levels, and you move through different bucolic landscapes, but by and large you can do what you want. Get the frogs on their lilies? There’s a bonus for doing that. Ditto the lost ducklings who need to be reunited. You could call these things puzzles, but they aren’t mandatory. They unlock lovely stuff in the menus, and the whole game is a bit like building a poem with earned pieces of text. But you can also skip as much as you want and just splash around.

This changes, however, and it took me a while to spot that it was doing so. The world of humans slowly intrudes, and with it bespoke puzzles which have to be untangled, often to open the route forward and move you onto the next section. Two things here: Naiad is sometimes an awkward puzzle game. It can be hard to work out what you need to do in some sections, while the dreamlike anti-logic that powered the first section – of course I need to chain together a movement through three purple flowers – grinds a bit in the second, when you need to clearly understand causality. So there’s that.

Naiad accessibility options

Players can control haptics, toggle screen shake and vibration, adjust screen flashing and have a directional prompt on-screen.

But there’s something else that redeems this a little. Naiad’s second half is not as much fun as the first, and that’s kind of the point. It’s a bit like how wild swimming isn’t as much fun in real life now that we’ve filled the rivers and oceans with sewage. I’m tempted to say that Naiad pollutes itself a little – increasingly grim settings, less freedom, much less sense of wonder – because it knows that you can’t responsibly make a game about how brilliant wild swimming is in 2024 without acknowledging all the ways that humans have made it less wonderful.

Naiad makes a brilliant point, in other words, and does it very effectively. Deep in the later levels I properly yearned for the early game, where the waters were blue and there were ducklings that needed me to show them the way home. Even late on, Naiad’s still interesting and glorious to move through – there’s trash in the water, but those currents still work their magic. But I think I admire it more for being willing to frustrate me a little, just to remind me that there are real things at stake, and the world of swimming, outside my local pool and my weekly lessons, is caught up in all this stuff too.

A copy of Naiad was provided for review by developer HiWarp.

fbq('init', '560747571485047');

fbq('track', 'PageView'); window.facebookPixelsDone = true;

window.dispatchEvent(new Event('BrockmanFacebookPixelsEnabled')); }

window.addEventListener('BrockmanTargetingCookiesAllowed', appendFacebookPixels);

Leave a Reply