Variable State has just unveiled Deepest Fear, its upcoming retro-futuristic survival horror game featuring Metroidvania exploration, immersive sim-like problem-solving, and a heaping dose of thalassophobia. Set within a sprawling facility deep underwater, Deepest Fear plunges players into a fight for survival as they work to uncover the station’s secrets while fending off nightmarish creatures that can suddenly appear from any body of water. The game features a sophisticated fluid simulation that forms the backbone of much of its problem-solving, requiring players to build dams and manipulate the flow of water to solve puzzles and keep the creatures at bay. Along the way, a series of Metroidvania-style unlocks open up new avenues for exploration, encouraging backtracking to previous areas for more thorough survival horror exploration.

In an interview with Game Rant, game director and co-founder Lyndon Holland, alongside co-founder and animator Terry Kenny, discussed the game’s unique blend of exploration, survival, and fluid-based puzzle-solving. They weighed in on how Deepest Fear aims to evoke terror in players, how the relationship between the game’s creatures and its fluid simulation creates tense situations, and how unpredictable events make each playthrough one of a kind. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Related

Deepest Fear Makes Water As Scary As Subnautica

Game Rant speaks with Deepest Fear developers about how the game’s underwater setting makes for a uniquely terrifying brand of horror.

The Classic Horror Films That Inspired Deepest Fear

Q: Can you lay out the broad strokes of the setting and what inspired the story?

Holland: We knew we wanted to make a horror game, an action survival horror game. I guess we were just thinking of things that would be really cool but maybe haven’t been seen in games in quite the same way.And also, how could the setting really enforce the type of creatures that would be there? We really loveThe Abyss,and we’ve actually thought about it in previous projects. We’ve always referencedThe Abyssfor the character development between the two main characters, husband and wife.

We found that to be a very satisfying character development in an otherwise mostly action thriller, so the idea then was that we could set it underwater in a facility that’s sinking and taking on water.

And the idea started going from that to, “Well, what creatures would there be? Maybe the creatures can come from the water.” That was the genesis of the idea. From the first principles: just an environment and then, from that, the idea of these creatures spawning from the water.When we’re thinking about the story, we want it to be more than just a plot—more than just “this happened and that happened.” There should be some thematic resonance that runs through the whole story.

We had this idea of a character who is thrown into a situation they’re completely unprepared for. It’s a time for them to learn something about someone they’re very close to from the past—someone they’ve maybe always known as a bit strange but have never really addressed head-on. Now, thrown into this situation, they have to confront these skeletons in their closet and things they’ve stored away at the back of their mind. They have to deal with them.

I’m being quite vague here, I guess, because of spoilers and things we don’t want to get into. But in broad strokes, I suppose it’s about finding the truth at the bottom of the ocean—the truth about someone you thought you knew, but maybe don’t know as well as you thought.

Kenny: I think it’s a perfect summary. I’ll just add that you’re put in this situation where confronting those things—those things about this person—is unavoidable, given the situation and the place you find yourself in.

Q: Water plays a unique role in Deepest Fear with its fluid simulation and the way enemies manifest from water. Can you talk about how that idea took shape? How did this focus on water affect the game’s direction?

Holland: I guess the main reason for pursuing it was we felt that it hadn’t really been seen in this way. We had some early experiments with the water system, and we thought it would be really cool to see aDead SpaceorResident Evil-type game in that setting.

We hope that’s a selling point forDeepest Fear. I think the swimming as well—the claustrophobia of potentially drowning. One of my favorite games isSubnautica,and there are moments where you’re swimming into shipwrecks and not knowing if you can get out in time. That’s not explored too much in the demo, but I think it’s something we can add to a survival game.

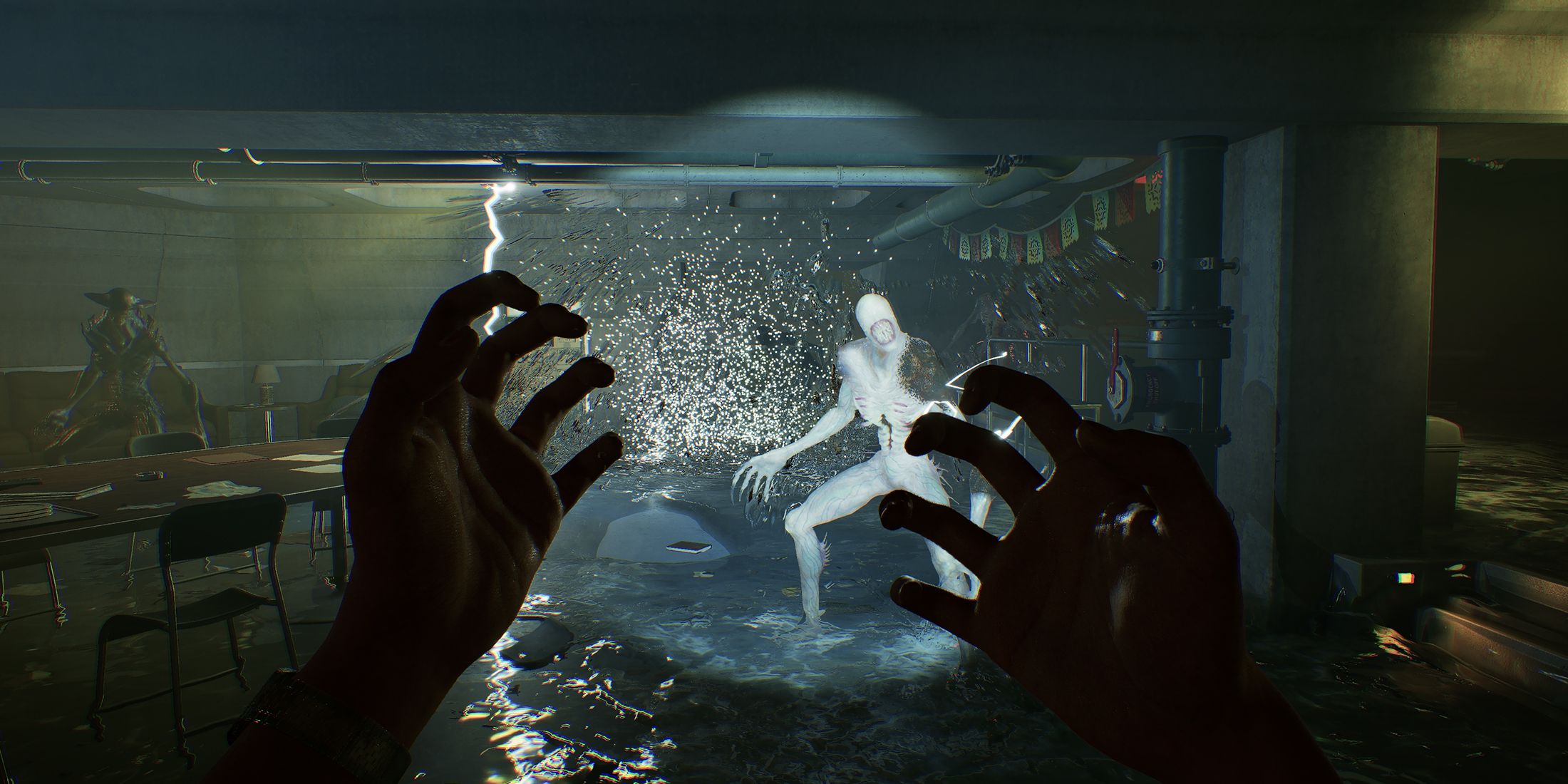

Kenny: I think that’s it. It’s situations like that—the fact that, anywhere there’s water, there’s going to be enemies. There are lots of areas where the floor is wet, there are puddles of water and sinks, and the place is constantly springing leaks.It allows us to have a fairly dynamic way of spawning threats, whether it’s enemies, the risk of drowning, or suddenly changing the environment. A place that might have been easy to get through when it was dry becomes a lot more difficult when it’s flooded. It just seemed to offer a lot of dynamism to the environment and gameplay.

Q: Deepest Fear takes advantage of Metroidvania-style exploration. Can you talk about how these Metroidvania elements come into play?

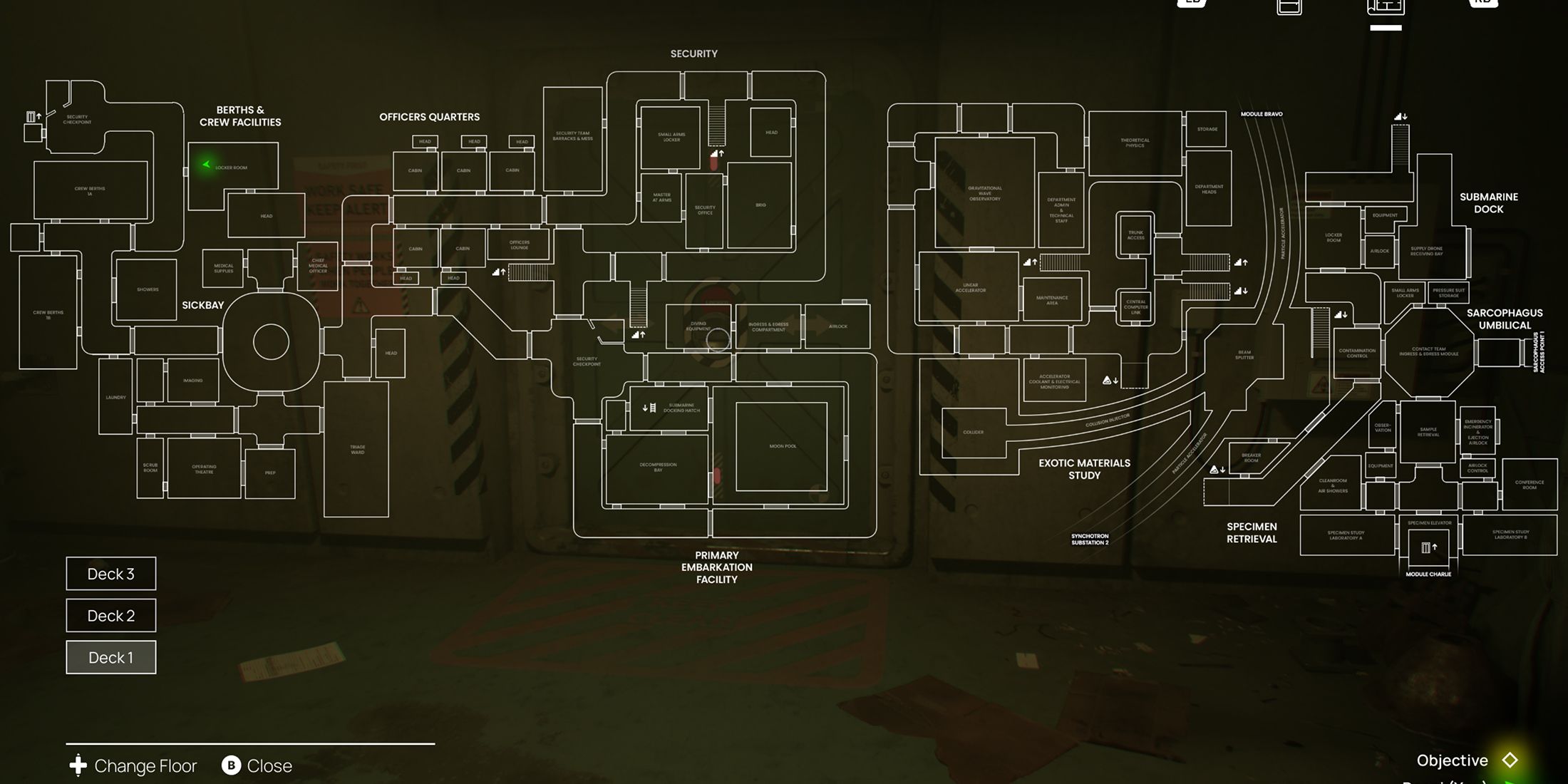

Holland: I’m always drawn to Metroidvania because it really leans on the player exploring an environment over a long period, rather than going into an area and never seeing it again. You can come back, see a locked door, and think, “Maybe I can open that later.” That’s a basic premise of Metroidvania.

I think, especially in a survival horror game, areas you couldn’t reach before—maybe because you couldn’t swim that far—take on a new meaning. Now, with a tool like a breathalyzer or O2 tank system, you can swim to a new destination, and it makes exploration feel fresh. Going back to an area and discovering something new about it adds a lot.

The lockdowns really play into that as well. Backtracking becomes more entertaining when an area can randomly go into lockdown. You won’t know when it’ll happen. We want to do as much dynamically as possible so that each playthrough feels slightly different. Maybe on your first run, you don’t get the same lockdown in a certain area, or puddles and enemy spawns differ.In a more linear level design, you can script those events because the player only sees them once. But with backtracking in the facility, we can keep it interesting by randomizing when lockdowns or surprises occur. Some of it will be directed—probably a lot of it—but having an element of surprise is really useful.

Q: Deepest Fear also takes notes from the immersive sim genre. Can you offer some examples of creative ways players might solve certain problems? Do you anticipate crafty players “breaking the game” as is an immersive sim tradition?

Holland: There might be puzzles you can solve in different ways. For example, you might get a tool that can fix something, or you could use your equipment to divert water.For instance, there could be an electrical box that’s broken because water got into it. You might be able to open the door the box is wired to by fixing it directly, bypassing it by taking another route or even building a dam to temporarily remove the water, fixing it just in time for the door to open before the water comes back. That’s one example.

We’ve got a grab bag of ideas for how the weapons we’ve built can double up as tools for exploring the world. That’s something we’ve been looking at, along with adding more dynamism to the stuff you collect.I’m a big fan of games like Prey,where you can pick up items and craft different things from raw materials.

Q: As a horror game, how do you try to evoke terror in players? What notes do you feel are important to hit for the game to be properly scary?

Kenny:That’s a really good question. I think what we’ve discovered—both by playing ourselves and letting others play—is that it’s often the combination of things. We can spend ages designing a creature, looking at a single image of it, and think, “That looks great, that looks scary.” But until you see it move, until you see it in context, until you hear it, there’s a difference. For example, seeing it in a large, open area versus a space where the doors are just locked behind you.

We’ve found it’s easy to try jump-scare moments—and we’re not ashamed of that. I think it’s fine to include those in the game to keep people expecting something terrible at any moment. But our effort has really been to keep the environment, even the dialogue, supporting a constant sense that something could happen—and whatever happens, it’s probably not going to be good.

Maintaining that sense of foreboding has been a trial-and-error process. For instance, there wasn’t much detail in the rec room when we first put it together, but it was still scary when the water came in and the creatures appeared. Then we started adding things, like the cinema room. You could imagine the people who worked there, having a good time before everything went wrong. If you look around the room, you’ll see decorations from someone’s birthday party, and that builds a sense that something really bad happened to these people.

There are a lot of levers to pull and dials to tune to keep that tension going. It’s been incredibly helpful to share the game with others. We record videos of people playing for the first time and watch their reactions. During playtests, there were moments we thought, “This will get them,” and it did. For instance, the first time we introduced water, with the whole “don’t go in the water, there are creatures in there” buildup, some players were absolutely terrified. We saw people swimming through the water, coming out at the other end saying, “Don’t make me do that again.”

To be honest, none of us approached this thinking, “We know exactly how to scare people.” It’s been about trying ideas and seeing what works. We’ve been surprised many times about what scares people and what doesn’t.

It must feel special to be working on a horror game and see players actually become scared.

Kenny: I hope that doesn’t make me sound like a mean person. I remember hearing that, and I don’t know… I’m a big fan of horror films and games in general. There’s a lot of fun in it. There’s a lot of tension that gets released in that little jump moment, you know?

So, yes, it’s definitely fun and exciting to see somebody enjoy the experience, especially when they get a fright and then confront it. That’s the great thing about horror, right? You get to safely confront things that, in real life, you’d do everything to avoid. But in a game, you kind of have to face it, and you get to do it in a safe environment and feel good about yourself for doing so.

Q: Speaking of that tension, how did you approach weapons and combat in Deepest Fear? As a horror game, do you feel letting players fight back too strongly could affect the emotional impact?

Holland: I think one of the most difficult points of balancing is, yeah, you want the player to feel underpowered and they are. They’re not like He-Man coming into a situation and just beating up everything but the game can’t come to a complete stop if you run out of ammo.

In the demo, we were a bit more generous with the ammo than we expect to be in the final game, mainly because of the way the demo was built due to time constraints. The demo is more linear than the game will be at launch.I suspect we’ll be much more brutal with ammo in the final version because there will always be a way to get out of a situation without relying on ammo. For example, in the rec room fight, it’s possible to get out of that situation without a gun. If you run out of ammo, you can still progress.

We built the demo to give people a snapshot of the game, but when someone only has a short amount of time to play, they might not have time to figure that out. With a longer playthrough, I think the experience could be much more challenging.

Q: What would you say are Deepest Fear‘s most unique qualities? What’s your “elevator pitch?”

Kenny: I’m sure we had several elevator pitches, but it’s kind of changed a lot over time. I think that’s the thing with an elevator pitch—you start with one, and as you begin making the game, you realize you need to draw inspiration from many other places.

Mike says, “Stay away from the water. Get out of the water,” in a panicked voice in an elevator. I hope that will have some impact.

Holland: Yeah, and I guess there’s a fear of swimming into deep water—being underwater, you’re already at a disadvantage because you’re much slower than you would be on foot.

As for the elevator pitch, I suppose, without being too reductive, it’s kind of like an experience similar to Dead SpaceandResident Evil, but meetsThe Abyss. It combines those elements you’re familiar with from an action survival horror game, but set in an environment where you’re dealing with water.

Q: About the game’s overall theme: What led you to go with an 80s retro-future style?

Kenny: The Abysswas a big influence. Strangely, it became something we became obsessed with, even beforeDeepest Fear. As Lyndon was saying, it’s the balance of that being a really great story about the characters, you know, coming to terms with the dissolution of their relationship and being put in a situation where they need to depend on each other again to survive. What that does do to their perception of each other—when everything else is stripped away and they just have to survive—how do they feel about each other now? Do they trust each other? And does that ultimately improve their lives and everyone else on board the ship or base?

That was a big deal from a story point of view.

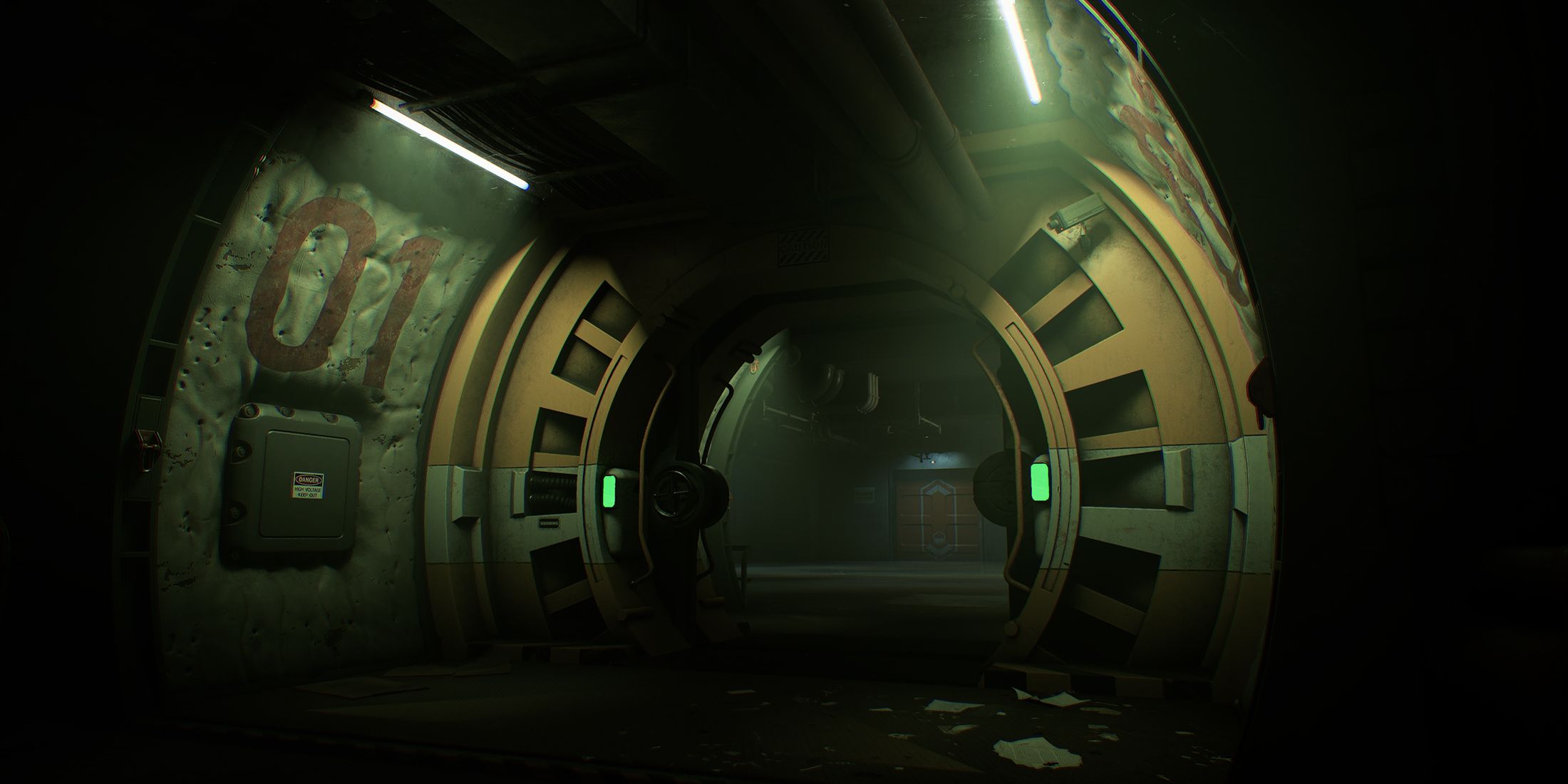

But when it comes to mood and atmosphere, we are all really big fans of films likeThe Thingand other John Carpenter films. I realize we’re not alone in this, so I always worry it’ll sound hackneyed, but those films really capture that sense of isolation and feeling trapped in a place. It’s obvious inThe Thingbecause they’re in a desolate area, but it’s the same inAssault on Precinct 13when they’re stuck in that base. It’s even in films like HalloweenandThe Fog—the opening shots ofThe Fog, where there’s nobody around, and it feels like this closed-in town with something creeping around it.

That atmosphere is something we were really keen on capturing withDeepest Fear. We’re all big fans of those films and their look.

Outside of that, the base is supposed to be a high-tech, military base for the time. From a visual and industrial design point of view, a lot of consumer 80s products are still recognizable today. For example, when you look at Sony Walkmans and things from that time, they’re iconic designs. We wanted everything to feel like that—touchscreens, switches, dials, and buttons, with a very nostalgic vibe. From an art point of view, that’s what we were going for. It was easy for us to do, as there’s such a passion on the team for those movies and their look.

Holland:We can’t even build that tech now, like to put a base of that size at the bottom of the ocean. It’s very much inspired by the Apple TV showFor All Mankind, which is a counterfactual—what if the space race didn’t end, Russia landed on the moon first, and the space race continued? You get to a point where they’re on Mars, or was it on the moon? They got a base on the moon in the 1980s.

You see that kind of future, realized in a retro style—what they call “cassette futurism.” There’s just a nostalgia for that, I think. For us, it’s part of the drive—just wanting to be in that world. Because if we want to be in that world, we suspect other people will as well.

How Variable State Crafted Deepest Fear’s Horror Atmosphere

Q: How did you land on Deepest Fear‘s soundtrack? What were your goals as far as the game’s overall musical and ambient style?

Holland: It’s such a small part in comparison to the whole game—it’s roughly a half-hour experience, so there isn’t a huge amount of time to flesh out all the major themes. Normally, what I would do is pick the big central themes, write those cues first, and then derive other pieces of music from that. But I approached it in a different way, just reacting to the energy required at any given moment.

I was really inspired by James Horner’s score forAliens, just how ferocious and wild it is, and avant-garde at the time—I still think it is, to be honest. I love that stuff, and it was an opportunity I hadn’t really gotten to write music like that before, so there was a personal ambition to write music in that mold.I wish I had more to say about it. I played the demo, saw where all the moments where we needed music, and I suppose, drew a line on a graph of what the intensity needed to be at these different moments. Based on that, I was able to determine what energy each cue should have at the different points in the timeline of the game.

Q: Did you feel that it was different from your past music work? Was there a learning curve?

Holland: I think so. I haven’t done too much of this sort of music before, so it was definitely a learning curve, but I found it a lot of fun. In some ways, it was quite refreshing to just do something different. In the past, I’ve been doing much more emotional, toned music. There are still some cues in there in the game, but to do something really dark and atmospheric was a lot of fun.

Q: On the visual side, Terry, you work a lot with Deepest Fear’s animations. Can you weigh in on the team’s approach to animating these creatures?

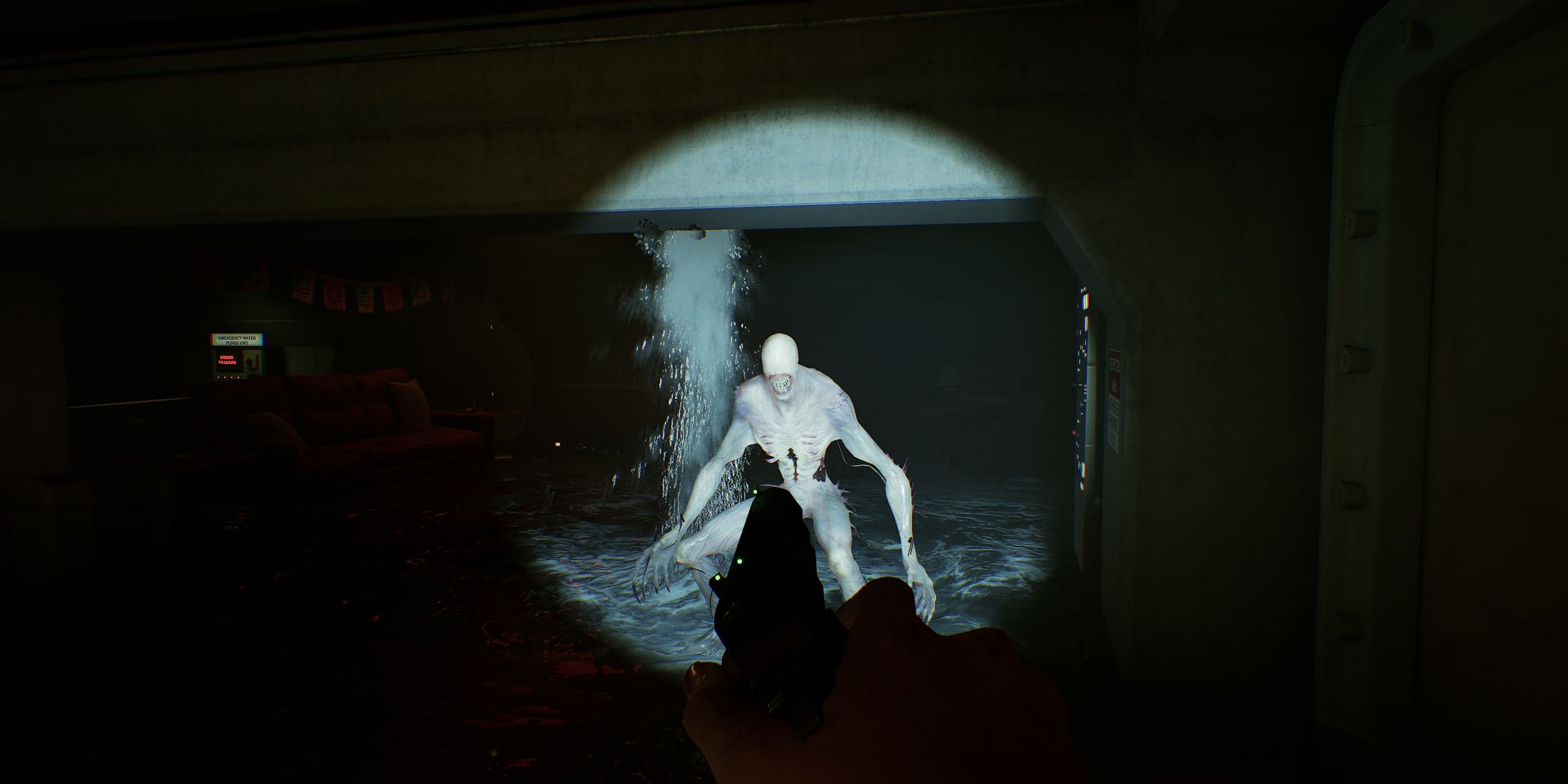

Kenny: I guess it kind of overlaps a lot with character design. What do the characters look like? That’s pretty obvious, but with animation, it’s the fundamentals of movement. We needed to ensure that the characters moved in a disturbing way, almost against how they were built. They’re mostly tall bipeds with two legs, two arms, and a head, so we’re all familiar with how to move around with those appendages. But what we wanted was for them to move creepily. We didn’t want them to look like zombies, though. Early on, we tried animating them to be creepy, but it started looking like typical zombie movements, which works if that’s what you’re going for, but we needed something more interesting.

In the game, the creatures alternate between standing up, where they can attack you at your height, and a crouched mode where they curl up into awkward positions. We filmed ourselves for visual reference, but some movements were just undoable. We looked at other horror films, especially J-horror, to see how they use creepy movement. We also looked at contortionists and people skilled in gymnastics for inspiration, trying to push those movements further into the characters.

Some of it worked, some didn’t. The challenge with video game animation is that even if you have a great walk cycle or a good crawl animation, it’s how those transitions work with the other animations. The real trick is figuring out how to transition from standing to crawling or other states. It’s a lot of experimentation to see what works and what’s creepy, but sometimes what’s creepy can end up being goofy. That’s something we ran into with some of our animations, but it’s been a fun process. It forces you to experiment in ways that you don’t have to in more straightforward action games. In those, the answers are obvious: you understand the character’s motivation, and the animations fall into place. In horror, it’s a lot more open-ended, and that’s what makes it so exciting.

Looking at contortionists is a great idea for creature animation. All respect for those athletes, but it can look a bit creepy.

Kenny: I think if you go too far from something recognizable, whether it’s the character design or their movement, it starts to lose something. It has to stay just on the edge of being recognizable, something I can understand. There’s an animation we didn’t show in the demo, where one of the creatures crawls over a sink. I think Noah, one of the animators, was inspired by watching a cockroach crawl out of a drain and how quickly it moved to get into position. It’s a huge character with arms and legs crawling, but when you look at the animation and think about it like a cockroach, it makes sense. You can feel that.

Q: Variable State previously developed Virginia, Last Stop, and POLARIS. Does Deepest Fear benefit from any DNA or lessons learned from those past titles?

Holland:I think with our approach to storytelling, especially inVirginiaandLast Stop, we’re still taking the same character-first approach rather than focusing on the plot. That’s really the backbone of what we’ve done in the past. It’s not about, “What’s the story?” but more about, “What’s the character? What are they going to learn? Why is this character in the story? How do they change by the end?” That part, I think, is really in our DNA.

Q: Earlier you mentioned player feedback. Can you recall moments where player feedback had a significant impact on something?

Kenny: I’ve got one! One of the things we had in one of the offices was a locker with an old-fashioned key lock, and we thought it would be really obvious. We thought, “Yeah, super obvious, no problem.” But I can’t remember if it was that we made the hitbox for shooting the lock really precise and small, or if we just assumed it would be obvious. But we were so confident it made perfect sense that we just left it there. Then when we saw all the playthrough videos, everyone was completely baffled about what to do. I can’t remember the exact details, but we all kind of kicked ourselves after that.

Holland: Some people tried to shoot at it once, missed, and then assumed the game didn’t let them do that. Others just didn’t notice it at all. After a bit of ballet with that, we added a highlighter effect on the lock itself. There’s like a periodic flash that goes over it, just to indicate that it’s an interactive item. We also added hints. If you wander around the level for a while, Michael will give you some hints, like, “I think the keycard’s probably in that room over there,” and if you take even longer, he’ll say, “Maybe it’s in the locker. Maybe you can shoot the locker door.” Those things we didn’t think we’d need, but after seeing people play, we realized some were getting frustrated. We just wanted players to be able to move on and progress the game. We added those hints in, and when we did a future playtest, those who didn’t get it straight away really appreciated the hint from Mike.

Kenny: I think that was it with the locker. The hitbox was quite small, so if you weren’t precise, it wouldn’t destroy the lock. I think people just missed, then assumed it didn’t work and moved on. We had to find a different way to handle that. Yeah, it’s amazing. Every developer has that experience where you spend so much time on something that feels completely obvious and understandable to you, but you really don’t know anything until you put the game in front of people. You don’t know anything until you see them play and hear what they think, or when they wander off into the world and find some collision issue you never even considered, or give you an insight or suggestion that makes you think, “Oh, geez, how did we never think of that?” It’s pure gold.

Q: Similarly, was there ever a moment in development where you tried out an idea and it wound up being a disaster?

Holland:In an early test, we were experimenting with the lockdown gameplay and how it worked. I think we had a much longer process for turning the valve, and it was more complex. We thought, “Yeah, let’s make it tactical.” But when we played it, it was actually really frustrating because everyone was getting attacked from behind while turning the valve. So we started streamlining it, simplifying it.

Then there’s the resin gun. We had a lot of design ideas to make dams easier to create, like shooting one side of the room and then shooting the other to make a connection and having blocks show up. We thought it would be easy to use, but it still felt cumbersome. Eventually, we simplified it so you just shoot blocks to make the dam, and that’s what’s in the game now. But even that can be a bit cumbersome.

We also had an idea that we didn’t include, which was a different weapon that would create a dam in a single shot. That would’ve been really useful because, in the chaos of the moment, you don’t want to be fiddling around trying to create this perfectly drawn line. You just want to shoot and know it’s going to block the water. What was happening in earlier versions was that water would seep through the tiny gaps the player hadn’t sealed properly. We started with something much more complicated, and in the end, we simplified it to just having a wider shot that breaks everything down. That worked.

We didn’t include that in the demo, but in future releases, there will be a gun that creates a water barrier in one shot.

Q: Any last thoughts before we head out?

Kenny: I want to have something really remarkable to say, but I’m not sure I do. I guess it’s just been a labor of love for everyone who’s worked on it. I just… yeah. I hope people enjoy it, and that it gets the attention it deserves. More than anything, I hope others see what we see.

Holland:I don’t have anything other than that we loved working on it, and we hope people respond well to the trailer.

Deepest Fear is currently in development for PC.

Leave a Reply