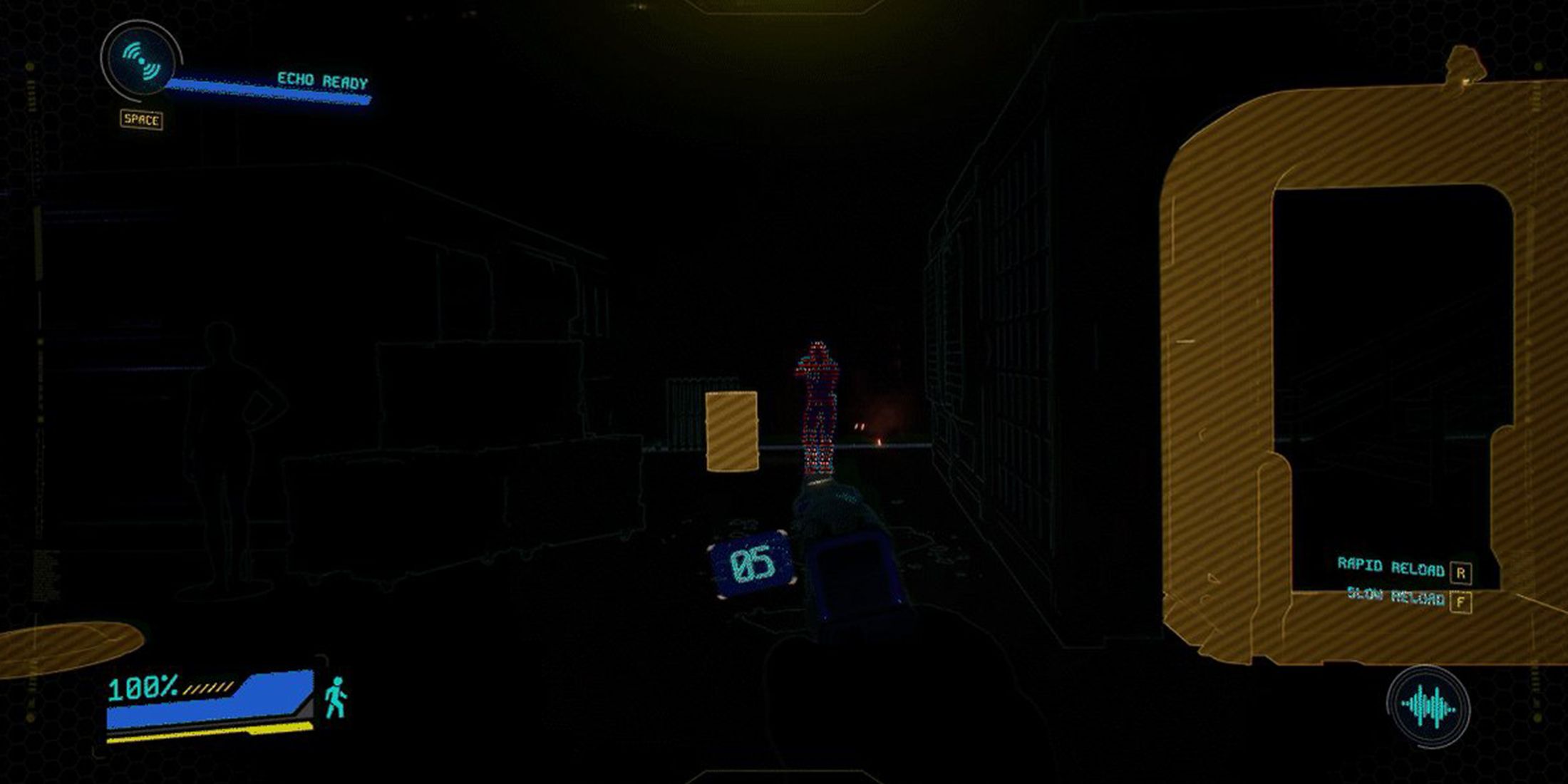

Double Eleven’s Blindfire has sneakily crept from the darkness to inject some much-needed innovation into the FPS genre by offering tense, tactical gameplay with a unique twist that tests completely different first-person shooter skills. Unlike other FPS games, Blindfire players fight in complete darkness: not only are other players obscured, but the environment itself is rendered nearly invisible. It’s not uncommon for two players to walk right past each other in Blindfire, resulting in some extreme tension building up until the first shot is taken.

Shooting is a huge risk in Blindfire since it gives away the player’s location, but being shot is even more dangerous as the player is illuminated for all to see. The first engagement in a round of Blindfire tends to snowball as players spot one another reacting to the shot, and whether or not to pull the trigger is a life-or-death tactical decision. Traps also litter the arena, risking exposure for hapless players. To top it off, these traps can be controlled by spectating players who have been eliminated. In an interview with Game Rant, Blindfire lead designer Matt Dunthorne spoke about the idea’s inception, Double Eleven’s approach to factors like level design and weaponry in darkness, and how the spectator-controlled traps solve a longstanding issue with downtime in first-person shooters. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

1:49

Related

Blindfire – PlayStation Release Trailer

Double Eleven’s FPS action game Blindfire is available now in Early Access on PlayStation 5. Take a look at the PlayStation release trailer here.

How The Idea of Blindfire Took Shape

Q: Fighting in pitch dark is a unique mechanic for a shooter. What inspired that idea?

Dunthorne: In my team, we’ve got a mix of experience, including a lot of junior designers. Something I set up was this thing called “Shatterday,” which we run every month. It’s simple, really. The idea is to get the junior designers used to thinking outside the box, pushing themselves beyond just what other people are doing, and trying to create something really unique.

Essentially, what we do is I set them challenges. They go away, brainstorm as a team, and then come back to pitch their ideas to the rest of us. Sometimes I’ll put together a big presentation. For example, the first half might be random selections of Nintendo games, and the second half random Xbox games. You might get something like Donkey Kong versus Halo, and they have an hour to come up with what that could look like.

One Shatterday, the challenge was to pick a genre—FPS came up—and then figure out: “What if you couldn’t see? What if the only way to see your enemy was to shoot?” So, the team went away, brainstormed it, and I joined in, giving them ideas and feedback along the way.

When I first posed the question, I thought it might turn into something like paintball—you cover the map in paint, and it eventually reveals itself, kind of like The Unfinished Swan. But what they came back with was this idea where it’s completely pitch black, and the only light source is the muzzle flash from your gun. Firing your gun in this environment is inherently dangerous, but it’s also the only way to win, so you have to figure out when to shoot and when to be cautious.

The idea spiraled from there. They pitched it to the room—there were three other teams—and everyone was really nice for all the presentations, but this one? Everyone was really feeling it. I went home that night and couldn’t stop thinking about it. A week later, I was still thinking about it.

At that point, I decided—along with one of the other lead designers—that there was something really special here. There was a core idea worth focusing on. We developed a small pitch and made a prototype in Unreal using assets we already had lying around. It only took a few weeks, at most, to prove the idea was worth pursuing. From there, we went to the board, got the green light, and started full production. It’s awesome that this whole thing came out of such a random, creative process.

Q: What were the challenges you faced implementing this idea? How does working on Blindfire differ from other shooters?

Dunthorne: FPS is almost the main genre where you need good sight and good reactions. Making it completely dark removes that entirely, which is a bit of a crazy idea to pursue. But the first problem we came across was navigation, as you might suspect—finding your way around in the dark is a challenge. At the same time, though, it was kind of exciting. Like, anything could be waiting in the dark. “What will happen if I keep moving in this direction?” That kind of thing.

We had to think about, “How does the darkness change the game? How can we rely on the darkness and make it the USP?” One thing I really liked was that, typically, when you’re in the light, you’re safe, and the dark is scary and dangerous—it feels like anything could happen. But in this game, we flipped that idea on its head. Light is really dangerous, and being in the dark is safe. You actually feel comfortable when you’re in the dark. That was a really nice concept for us to lean into, something we could use to differentiate ourselves.

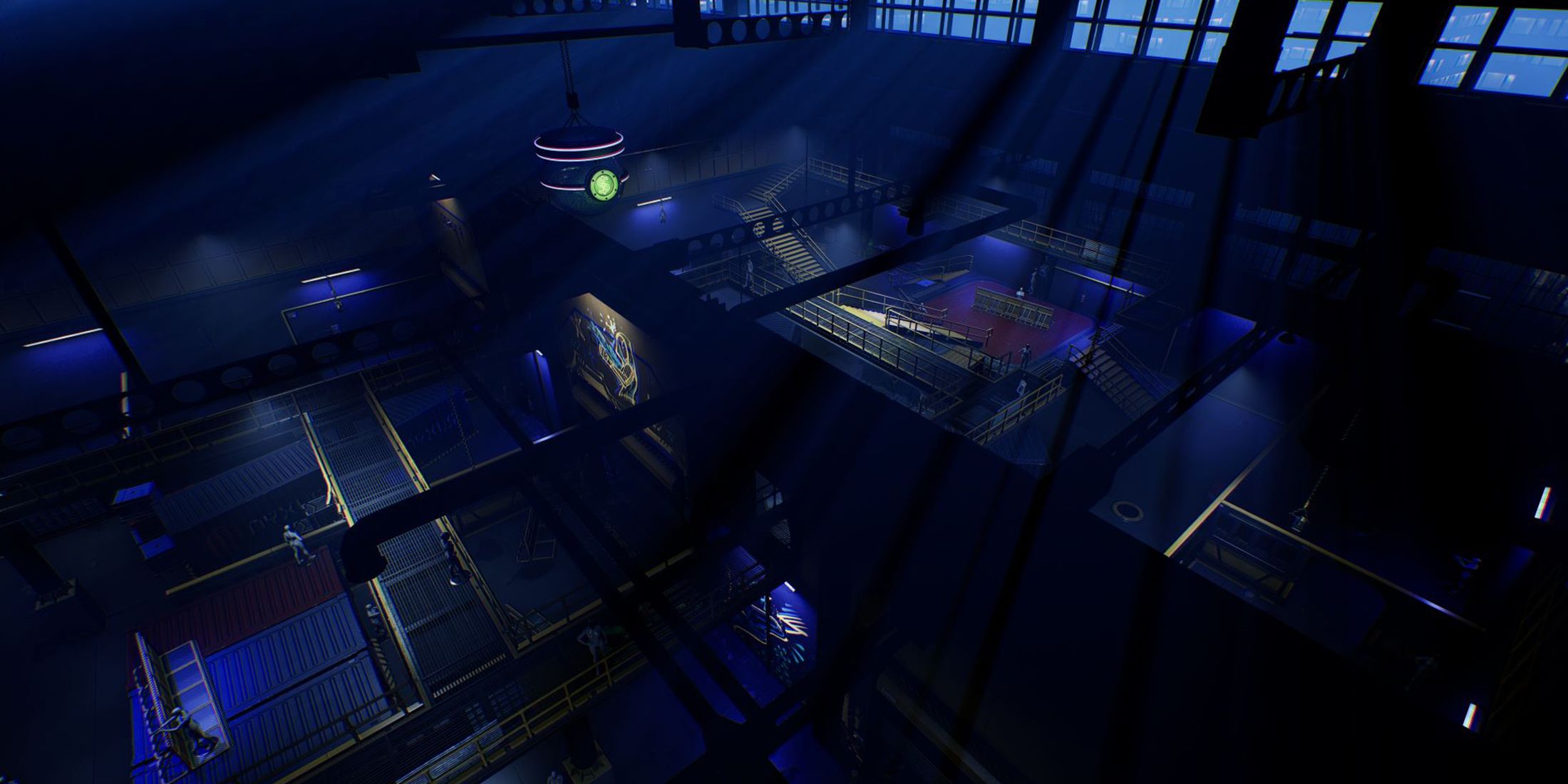

In terms of level design, the space completely changes when you take light away. We could make things really small. We didn’t have to create giant, modern levels or worry about lanes or chokepoints or any of that stuff because essentially, the entire level is a chokepoint.

Audio was another massive deal. We have a really, really good audio team—very experienced—and this project was like their dream come true. Something set in the dark, where players have to rely completely on audio? That’s amazing. They focused on making the environment feature lots of different materials so that footsteps, for example, are slightly exaggerated.

If you’re walking on metal, concrete, or glass, you know what you’re stepping on. When you bump into a container, you know it’s made of metal. Walk through the container, and you get different reverb effects. All of that was critical. We really had to think about what materials to include in the levels so players could understand their surroundings just through sound.

The main mechanic we added was something called Echo. It’s an ability triggered with the space bar, which sends a pulse out and outlines everything around you. It also reveals enemy positions temporarily. There are levels to how Echo works, too. For instance, if you bump into something, it gets outlined briefly. Static objects like walls and giant pillars that never move get a permanent outline in your Echo. So, there are essentially three stages of how you can see the level briefly, even though it’s dark.

The darkness itself also allowed us to add lots of surprises. You don’t always know where you’re walking, and if you’re not careful, you might trigger a trap or encounter some unexpected obstacles. It really added to the tension of the experience.

Q: What would you say are Blindfire‘s design pillars? What traits are important for you to focus on?

Dunthorne: The kind of ethos we followed—our tagline, really—was “Hollywood shootout in the dark.” We wanted it to be dark, obviously, but we also wanted to capture that Hollywood touch. Specifically, we were inspired by neo-noir cinema, and John Wick was our hero reference for this.

We wanted the gunfire to feel larger than life—very visceral and impactful. The VFX had to be bigger, and we wanted the player to feel like John Wick. They’d be using all their senses—hearing, brief flashes of light, and spatial awareness—to pinpoint enemies in a completely dark room and still come out on top because they’re the best shooter.

Another core pillar for us was tension—tension and release. What we found with the concept, naturally, was that the beginning of a round, when it’s all dark and no one knows how things are going to play out, is very tense. The longer that tension lasts, the more it ramps up, building and building.

Then, when the first person fires their gun, it’s like the starting gun in a race. The tension is instantly replaced by adrenaline, and it’s just chaos. You’re scrambling to get out of the way, thinking, “Oh my god, there’s someone—I can take them out!”

But when you shoot them, there’s this whole layer of uncertainty. Did you give yourself away? Is someone else watching you now? It becomes this incredibly fast-paced game of tactical chess—trying to take out your target while not staying still too long or exposing yourself to danger.

Q: Were there any games you looked to for inspiration? What kinds of games do the Blindfire team tend to play? In some ways, it reminds me of the Splinter Cell ’s multiplayer back in the day.

Dunthorne: Yeah, you mean the multiplayer Spies vs. Mercs mode? Yeah, there were quite a few fans of that mode on the team. I didn’t play it myself, so I had to look into it. I don’t think you can play it anymore, but yes, in terms of the shooting style, we went through the motions of deciding whether it should be realistic or more arcade-like.

What we found worked best was something like the CoD-style shooting. We didn’t want aggressive recoil because that would take away from the John Wick feel. If every shot made your gun fly all over the place, it didn’t give you that feeling of being in control, like you would expect in a game where you’re the best shooter. We played a lot of CoD and drew from that for the arcade feel, but other than that, we tried our best not to be overly inspired by other games.

The reason we wanted to make Blindfire was because it was unique. We knew that to release something that stood out in today’s market, it had to be different. My ethos with the team is to look at other games, do the research, and tell me why something like that would work in our game, or how we can make something like Blindfire work. How can we make you feel more like John Wick? We’ve tested a lot of multiplayer shooters over the past year. Most of the team are huge FPS fans, except for me—I just don’t play them well enough.

Q: Can you talk about Blindfire ‘s early days? How much has the game changed as the concept took shape?

Dunthorne: It’s actually remarkably similar. The prototype we put together before we got official permission to make the game was really basic—it was just a white room with no objects at all. We had eight people loading in, and then I set it up by putting a point light on the end of a gun from an asset pack. When you fired, the point light would flash, and I put point lights all over the players’ bodies. When they got hit and took damage, those lights would turn on. But essentially, that was the core of the idea, and it hasn’t changed much since then.

The shooting is dangerous, and being shot is even more dangerous. We always wanted to make it feel like if you fired your gun and exposed yourself, as long as you hit someone, if you were playing cleverly, they’d be more exposed and the heat would be taken off you. That was the key idea behind that first prototype, and it worked. It was enough to inspire us to push forward and pitch the concept to the board—there was something here, and it was already fun, even with just six white boxes, four mannequins with cheap guns, and white lights.

From there, we tried a few different things. For example, originally we had overtime mechanics where the lights would come on. We even had walls closing in, like a trash compactor from Star Wars. We kept that for quite a while, but it turned out to be very restrictive in terms of level design. Everything would have to be a physics object, and all the walls would have to deform or destroy everything they touched, which was too much for the size of the team and the time we had to work with. It also confused the players because they’d think they were safe, but suddenly the walls would push them along, and since it was pitch black, they couldn’t see what was happening.

But yes, we’ve been remarkably true to the original concept. The very first story we pitched to the board was done in Google Slides. We showed them a prototype, and it was literally just a pitch-black slide.

When we clicked, we added a Metal Gear Solid-style exclamation point to show, “Oh, you’ve heard someone.” Then we clicked again, and you’d see a flash of light where you shot, but if you missed, we clicked again to reveal that you’ve lighted yourself up, and then a final click would show someone right in your face, and you’re dead. That was the very first prototype—six slides. But it conveyed the idea, and we’ve kept that core concept all the way through to now.

Q: How does the darkness influence weapon and equipment design?

Dunthorne: We found that the pistol—the classic pistol—was the best fit for this game. The pace and the darkness made it feel just right. It allowed players to feel clever by finding someone and then skillfully taking them out.

But then we went to the other extreme, and we thought, “Wouldn’t it be fun if you were in pitch black and everyone was firing shotguns?” Once we implemented the shotgun, it created a much more chaotic environment. In a shotgun round, once the first person fires, it leads to a much quicker resolution. There’s a lot more chaos, and we liked that contrast.

Players could either have these slow, cautious pistol matches or these crazy, chaotic shotgun matches. That mix felt fresh, especially since we were designing a five-round mode for our first mode.

We also have some new guns coming out soon, like an auto-pistol and a burst shotgun, which is a bit unusual but adds variety. The core idea is still there, though: pistols are for slower, more methodical gameplay, while shotguns are for a more chaotic environment.

Q: How do you feel the darkness affects players’ approach to gameplay? Does the game test different skills than a typical shooter?

Dunthorne: That’s why I’ve really enjoyed working on this game—I’m terrible at shooters. I can design one; I’m good at that. But playing them? I’m awful. The team teases me about it every day because of how bad I am.

But here’s the thing: in Blindfire, I can out-think someone and get a result, rather than having to outshoot them directly. If I use my Echo well, if I know where people are, and if I can listen and use my other senses to gain an advantage or get the jump on someone, it means I can afford to miss a couple of shots. When they start firing back, I’ll see them, and I can try to line up a headshot.

It doesn’t always work because, again, I’m terrible, but it gives me a chance. It feels like a level playing field.

During some of our player tests, I noticed that some people just run in and start shooting right away—guns blazing straight from the start. They die quickly. After about five matches, maybe an hour into the playtest, that behavior shifts. People start waiting, holding back, and that tension builds. It’s really cool to see how players adapt over time.

I love that it’s a level playing field. I also love that people like me—who’ve only ever had Halo to fall back on because of the armor system—now have a chance to succeed by thinking deeply instead of just relying on shooting skill.

It’s great how accessible the game is for gamers who might not necessarily have the strongest twitch reflexes.

Dunthorne: One of the nicest things for the team has been that we’ve had several high-profile accessibility advocates reach out to us. They’ve said things like, “This is so close to being the very first FPS that blind people can play,” and they’ve thanked us for creating such a unique concept.

What’s really amazing is that this game puts everyone on the same level of disadvantage they experience, if you know what I mean. They’ve also given us lots of suggestions on how we can improve things. In the coming months, we’re going to work on making this the very first FPS that a blind person can play and be competitive in.

Q: On the subject of accessibility, how do you think you could approach Blindfire’s accessibility for players who are hard of hearing?

Dunthorne: We’ve had to be really upfront about accessibility. Right at the beginning of the game, it says, “Best played on platforms where you can hear,” but that’s something we didn’t want to shy away from. That said, we have design documents full of ideas on how the game could be played by people who are hard of hearing. A few games have attempted similar things, like using ripples to show where people are standing or visualizing sounds with VFX. We’ve got designs that could take us to a place where that’s possible, and it’s definitely something we want to do.

Right now, though, the biggest win for us in terms of accessibility is going to be for blind players. Hopefully, if we can gain some traction, we’ll work toward implementing that sound visualization in the game as well.

Either way, making an FPS that blind players can enjoy is a commendable undertaking.

Dunthorne: We wanted to make it as accessible as possible. We had to put it out in Early Access, so we haven’t done all the things that we’ve planned, but the audio team’s dedication to positional sound is being recognized and seen as a positive and our community is just best in class.

Q: Time to kill (TTK) is an important consideration for shooters. What was your approach to Blindfire ‘s pacing in combat?

Dunthorne: We’ve gone through every extreme with the time-to-kill during development. What we found is that when you slow down the pace, a longer time-to-kill feels more rewarding—especially when the gameplay is focused on finding someone and exposing them. The catch is that you need to do this while keeping yourself safe. A single headshot, for example, felt cheap—it was a bit too anticlimactic. You’d put in all this effort to find someone, and then they’d just drop instantly.

We also realized that we didn’t want people sprinting around in the dark, jumping, or doing flips because that’s not what you’d do in a dark environment. We don’t think John Wick would do that in the dark, either! So, we slowed everything down. And what we found is that a longer time-to-kill feels more rewarding and makes engagements feel more dangerous. That danger—the sense of risk—was something we wanted players to feel when they decided to engage.

How Darkness Impacts Blindfire’s Approach To Game Design

Q: How does the importance of sound and light influence Blindfire‘s level design? Do you have to look at levels differently?

Dunthorne: Yeah, definitely. The main thing—and I guess I kind of touched on this earlier—is that taking the light out of the equation lets us condense things. For example, spawn points don’t have to be hidden or safe because everywhere in the map is safe to a point. Of course, we make sure there aren’t light traps above spawn points, just to be fair.

When you remove light from the equation, everything can be a lot more compact and closer together. One of my favorite things to watch during playtests is the spectator mode. You can see the entire map with the lights on, and I love it when two players walk right past each other, completely unaware of each other. We love moments like that.

To encourage those close encounters, we designed narrower sections in the map. Initially, though, we found that players would just head to a corner and stay there. So, we implemented an overtime mechanic—kind of like a battle royale. After a certain amount of time, the corners light up with UV lights, making anyone in those areas visible and vulnerable.

A bit later, we bring in the side walls, and if the round goes on for too long, we bring in the top lights, illuminating the entire map to force a conclusion. Before that, we had people camping in corners for ages, which could be fun, but for this mode, we wanted rounds to be snappy and resolved quickly.

On top of that, we also had to add an anti-camping feature. If you stay still for too long, your mask lights up, revealing your location. The game essentially tells you, “Don’t be a camper.” One of our main goals is to keep players moving so that they have to make noise—their footsteps have to be heard.

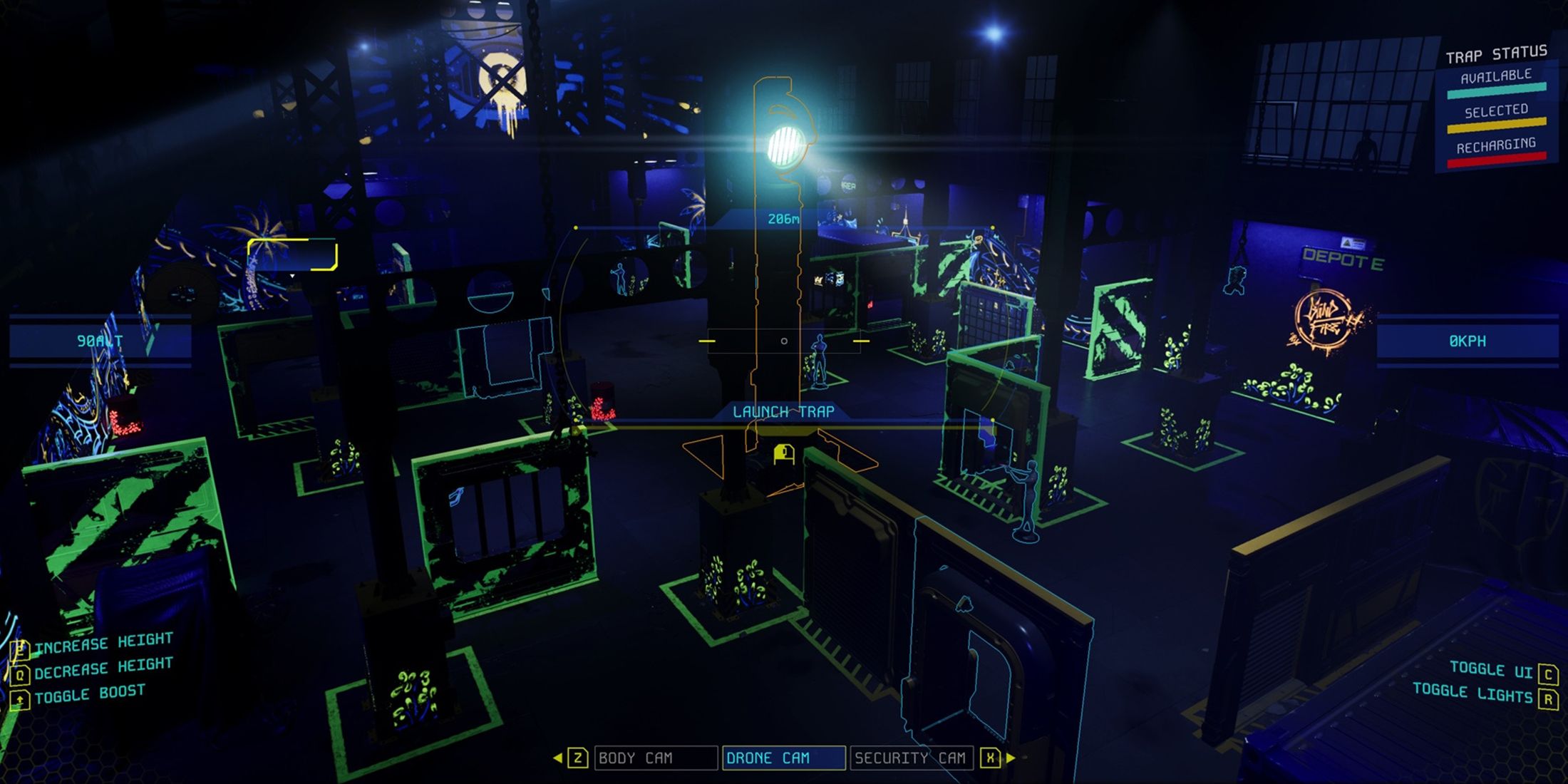

This keeps players moving while also staying aware of their surroundings, which added a lot to the gameplay flow. It especially affects how traps work. You can be as careful as you want, but if someone in spectator mode is controlling the traps and they decide to turn on a light above your head, you’re forced to react and change your plan.

Q: How has Early Access benefited Blindfire so far? Has player feedback had a strong impact in certain areas?

Dunthorne: It was a rough launch. Initially, we were just planning on supporting Steam, but we pushed ourselves to also support Xbox. It was a big step for us. The original idea was Steam only, but we added Xbox, and that meant doubling our work. We did the Xbox build in about three weeks, from start to finish. It wasn’t fully compliant, but we got it working in three weeks, which was pretty good. Then, because of that, it had to go through compliance testing with submissions and approval. That was a whole process, but we got it out on stage. It was a rough launch, though, because the timing didn’t match up perfectly.

We found that the players who did join us really enjoyed the game. Everyone was saying, “This is a really cool idea—what if you did this?” The core idea of the game has inspired people to think about how they would improve it. “What if you had this feature or that feature?” And that’s been great for us because it gives us lots of things to work on and improve. It’s an idea that excites people to be involved. They want to see more, experience more, and share their opinions.

We’ve got an active community on Discord, and we listen to their feedback all the time. We’ve been very active ourselves. I think we’ve done three patches in the first month, with a lot of quality-of-life fixes, bug fixes, and server improvements thanks to our coders. We try to be transparent with our process, letting people know what we’re doing next and when patches are coming out. Our community is very responsive, and we try to play with them a lot too. We tell them, “The dev team is playing tonight, jump in and play with us!” There’s one person on the dev team who literally murders every fan we have, and I wish he’d stop, but that’s just how he is.

Early Access has been really cool so far. A lot of ideas have been generated, and we’ve got a solid core group of people who love the idea. It’s really resonating with people, and they’re excited to see more content. That feedback is helping shape our content updates.

In fact, we’ve got an update coming out before the end of the month that brings a new game mode called “Kill Race.” It’s based on feedback from players who enjoy the Counter Strike-style rounds where you score points. The player with the most points at the end of five rounds wins. People coming into the game wanted more of a deathmatch experience, so Kill Race is our twist on that.

We’re also bringing in new weapons, like an auto pistol. People kept asking how crazy it would be to have a machine gun in the dark. While we couldn’t pull off a machine gun in a month, we’ve got the auto pistol, which is like a little Uzi. It’s super fun to fight with in the dark. We’ve got other things coming too, like windows and new environmental elements that people are asking for.

Early Access has been a great experience for us. We’re a small team—Double Eleven is huge, with 400 people, but we’re a small team within that. This is our first original game, and we’ve been trying for 15 years to get to this point. We wanted to take it slow, use a small team, and test a unique idea to see if people would resonate with it, and they did! The crazy idea of an FPS in the dark actually works, and it’s been exciting to see people get so interested in it. It’s been a cool journey, and we love watching people experience the game and say, “Oh my god, what the hell is going on here? Why is this game so addictive?”

Q: You mentioned the trash compactor idea. Were there any other things you tried during development that ended up being a bit of a disaster?

Dunthorne: It was really hard to find the sweet spot between too much information, too little information, and getting the frequency right—too frequent or too infrequent. When we first implemented a team mode, like Team Body Count, I thought it would be really fun if you were in a pitch-black room and didn’t know whether the person you were shooting was on your team or not. I thought that was hilarious. It sounded cool to me. But when we tested it, everybody hated it.

In my mind, I thought, “Oh, this is fun. I didn’t win that round, but I had a laugh. I shrugged it off, even if I got shot by a teammate.” But the people we were testing the game with—internally at the studio and in external playtests—they were like, “I’m getting team-killed constantly. This is terrible. Why have you done this to me?” That was one of our second external playtests, and the team mode got completely tanked.

It gave us a lot of valuable feedback, though. It encouraged us to think about signs and feedback, and we realized we needed to make sure players knew which team they were on and who they were playing with. We made it so that the last known position of the enemy would be shared among the team. We highlighted teammates with their team color and made it explicit—”You’re on Krakens” or “You’re on Riptides”—so there was no confusion.

The initial implementation of Echo (the team mode) was a massive challenge, but our VFX artist is a genius. I don’t know how he did it, but it’s the most complicated material I’ve ever seen in my life. The first time we put Team mode in the war games (which we play every fortnight), it was a little deflating for the designers. It taught us a lot.

Q: Another unique aspect of Blindfire is how defeated spectators can influence the match. What was your approach to this idea? How did you decide how much impact spectators should have?

Dunthorne: The reason we went in that direction with spectator mode—well, initially, the concept was kind of like a game show. We wanted to make sure that the viewers could be involved. The idea was that once you’re out, you could still watch the match, which felt like getting a sneak peek at the map with all the lights on. You could see how people were playing and learn a little bit about how to approach the next round.

Then it was like, “Well, we’ve got all these traps, and we’ve got players flying around and seeing things from different angles. What if the spectators didn’t just watch, but actually took part?” So we introduced that idea, but once it was in play, we realized that if you have too many traps, it can become chaotic. In an eight-player match, if six players are out and the six lights come on all at once, it’s a little too much. We dialed that back a bit and made sure there was a mix of sound and light traps. We also made sure to use a variety of materials for the traps.

We try to make it so that each trap has a different effect depending on whether a spectator triggers it or a player does. For example, if a player bumps into a car, they get a black-and-white flash of lights. But if a spectator triggers it, there’s a burst of sparks to show that the spectator activated it. Then you get the full siren and longer lights, so the player knows, “Right, someone’s trying to mess with me. I need to be even more careful.”

In the next update, we’ll also allow spectators to earn points. They won’t earn a lot, but if they use their traps carefully, they can earn enough to stay in contention and not feel like they have no chance of winning by round four.

We really love spectator mode. We love that there’s no downtime. Even though the rounds are short, you don’t have to sit out completely—you can still stay invested in the match. You can help your mates if you want to, and that’s a really good feature.

That’s actually a brilliant solution to a longstanding issue with FPS games—the downtime players experience when they’ve been eliminated.

Dunthorne: We’re really proud of the spectator mode. We’ve put a lot of effort into it, and in the December patch—not the next one, but the one after—we’re adding more interactive elements. Right now, we have something we call the Eye of Sauron, where spectators can take control of a searchlight and move it around slowly, but that’s the only thing they can currently possess.

We want to add more objects that spectators can possess because it’ll make things a bit more fun and engaging. As I mentioned, in the next patch, spectators will be able to start earning points. If they trigger a trap and someone dies within a certain time frame, they earn points. This way, they’re incentivized to not just watch but to actually get involved. We’re really happy with how it’s turning out.

Q: What are some of the team’s focuses moving forward? Are there certain areas of Blindfire you’re really interested in fleshing out?

Dunthorne: For me, one of the big inspirations, when you asked about them earlier, was getting voice chat into the game as soon as possible. Our audio team cares a lot about audio quality because it’s so important to the game flow. We didn’t want to just throw in a basic voice channel that drowns out all the footsteps and other important sounds. So, we’ve taken a more complicated approach to voice chat, which has taken a bit longer to implement.

I think once it’s in, it’ll be really fun. Players will be able to talk to teammates, or if they’re in a team mode, they’ll be able to talk to other dead players. They’ll even be able to sneak up behind someone, whisper in their ear—it’s going to add a lot of laughs and create those viral moments.

Voice chat is one of the biggest things I think is missing right now. The inspiration for it came from games like Content Warning, where you can only hear your teammates if they’re close by, and you can hear when they’re getting scared. It’s going to be a huge addition.

We also want to introduce more game modes. We have a new one coming before the end of the month, and we’re working on features like custom lobbies where players can choose their rules—things like whether overtime is on or off, or what type of goal to play for. We want players to be able to play the way they want to play. I’ve always loved Halo and Forge Mode, being able to create custom game modes, and I want to give players that kind of flexibility, eventually.

We’re also thinking about big things for customization, like letting players change designs on their avatars, and adding a ranking system, so players can unlock more options as they progress. We want to give players long-term goals. It’s important to us that players don’t just have fun in the moment but feel invested enough to keep coming back and keep playing. Player retention and rewarding systems are a big focus for us.

A lot of people in the community are asking for ranked matches. That might take me a bit longer to get right. I want to make sure the core of the game is solid and competitive before introducing ranked mode—so that it has legs and something that players want to compete for. I think the current focus is more on having fun with your friends, having a quick session without the pressure of ranked play. You can still enjoy the game without grinding or worrying about battle passes. That’s the kind of vibe we’re going for.

We never wanted to challenge Call of Duty and say, “This is the FPS.” What I’ve said to the marketing team is that, back in the day, everyone had a PlayStation or an Xbox—and also a Wii—and you had Call of Duty, Battlefield, or whatever. Those were the main FPSes, and we didn’t really care about competing with them. We’re the Wii. We just wanted people to have fun with both types of games. Ranked mode is coming, but it might take a little time. We’re building it based on what the community wants. We’ve got some crazy ideas.

Blindfire’s Future Plans

Q: You mentioned Battle Passes. Is that something you’ve considered implementing in Blindfire?

Dunthorne: We have no intentions of going down the Battle Pass route or any monetization during Early Access. We can’t be sure what the game will turn out to be, or what version one will look like. If it goes free-to-play in the future, then we’d need to think about monetization options like Battle Passes. Personally, I’d rather focus on features like the rank system I mentioned earlier. That’s all free content, and it’s not tied to a Battle Pass. It’s more like how it used to be, where you were rewarded for being good at the game or playing a lot.

I love that idea—just like in Halo 3, where the more you played, the more XP you earned, and the more customization options you unlocked for your suit. That’s what we’re aiming for with this feature. We want to give players those rewards for putting in the time and skill, not through a Battle Pass. We’re working on a retention mechanic that keeps players invested without pushing them toward monetization too early.

That said, I can’t rule out Battle Passes entirely. It’s something we’re looking into for the future, but we don’t think it’s ethically right to implement something like that during Early Access.

Q: There are some interesting items on the Roadmap heading into 2025. Can you talk about some Roadmap plans you’re particularly excited about?

Dunthorne: We have a game mode on the roadmap called Spotlight, which I think could be really fun and unique. It’s a bit like Oddball in Halo, where you have to control something to score points. But in this case, the thing you’re controlling is a light. Holding the light makes you light up, which is inherently dangerous, but you have to do it to score. The concept is all about putting yourself in danger to win, and I think that’s a really cool idea.

For the team mode, we’re making it so you can pass the light between teammates smoothly. This way, your team can keep scoring points, even if players are exposed for short periods of time. There’s also the idea that my combat designer wants to add a Dragon’s Breath shotgun—basically, a shotgun that spews out flames. In the dark, I think that would be awesome.

Then, of course, I’m really excited for voice chat. I just want to get some jump scares in, whisper in someone’s ear, and then shoot them in the head. I don’t know what that says about me.

Q: Any last thoughts you’d like to leave us with?

Dunthorne: I feel like I’ve covered a lot of the things I wanted to talk about. One of the things we wanted as a team was to create something that felt truly unique, something that couldn’t be compared to anything else, and I think we’ve achieved that. The response from the fans has really solidified that feeling. We’re just really happy that people have given it a chance and realized that the special thing I saw all those months ago in the pitch—it’s still there. We were right to pursue it, and that feels incredible.

[END]

Leave a Reply