Eurogamer’s week-long coverage of PlayStation’s 30th anniversary begins today with a very special interview: an extended conversation looking back behind the scenes at PlayStation’s original launch, how the brand became a breakout success despite established competition, its “Icarus moment” in the PS3 era, and then its ongoing battle for industry dominance.

Few saw more of PlayStation’s last 30 years than Shawn Layden, who was already at Sony when the company’s console ambitions were first forming. Over more than three decades, Layden became a pivotal figure within its gaming division, and ultimately served as Sony’s chairman of PlayStation Worldwide Studios.

Layden began his tenure tasked with bringing countless games to PlayStation, and ended it by overseeing the launches of PlayStation’s biggest blockbusters from its own development powerhouses. Now, five years on from his 2019 departure after an astonishing 32 years of service, it was high time for a catch up and look back at everything PlayStation had achieved – and how it all began on a huge gamble.

What’s your first memory of PlayStation? You were already working at Sony at the time, what was your reaction to it? Was the idea of a games console taken seriously?

A ‘fool’s errand’, some of them might have even called it at the time

Layden: When PlayStation launched I was still with corporate, back at Sony headquarters where I’d been since 1987. I was attached to the office of the chairman, Akio Morita, the founder of Sony. I was his assistant, speech writer, ghost writer, interlocutor when I had to be. And we were watching all that from afar, so to speak. But I remember having a presentation early on where they brought the PlayStation prototype to the chairman’s office, and we got to see what they were building. I remember back in mid ’94 before the launch, standing up in a boardroom playing Ridge Racer and going, ‘oh my god, this is going to be fucking amazing’.

But within Sony, I think a lot of the leadership at the time didn’t take it seriously. They thought: ‘Oh my god, Sega and Nintendo own this thing [the console industry]. You think Sony’s going to come in sideways and try to divvy that thing up into a three piece pie?’ It was a ‘fool’s errand’, I think some of them might have even called it at the time. But [then-Sony president Norio] Ohga-san was a believer. A lot of people thought we were taking a risk. It was a fight to get the Sony name onto the machine – they didn’t want to be associated with it.

You moved over to the PlayStation division specifically pretty soon after – how did that happen?

Layden: I joined PlayStation specifically in ’96 when they were a year into it. They’d already launched in North America and in Japan. Sadly, the chairman had suffered a stroke, so that position was no longer required, and the president of PlayStation at the time was a guy named Terry Tokunaka. We’d worked together on the acquisition of Columbia Pictures, so I was kind of a known quantity. After the chairman’s death, Terry asked me ‘what are you going to do now? Why don’t you come and join us in this new company, Sony Computer Entertainment?’ I said, ‘Okay, that’s great. What would I do there?’

He said: ‘You’d be a video game producer’. I said: ‘I’ll be honest with you, I don’t know anything about making video games’. And Terry was very upfront. He said, ‘It’s all right. None of us do either. This is the perfect time to get in. We’ll all make this stuff up as we go along together.’

What was it like actually working inside PlayStation back then?

Layden: Talk about baptism by fire. I was walking around trying to get to know people in my first week and my boss comes up and says, ‘Hey, are you going to E3? Because that’s next week’. I said, ‘Do you want me to go to this E3?’ He said yes I should go. ‘Great!’ I say, before finding a colleague. ‘What the hell is E3?’ I didn’t have business cards, and I landed in LA in 1996 going to E3 after only being in the company for 10 days. If you want total immersion in the game business as a neophyte, get dropped into E3 on day 10. You either catch on really quick, or you get rolled over by the leviathan. You just have to run faster than the slowest bear, as they say.

PlayStation faced established competition – Nintendo, Sega were already giants of the console world. How did Sony decide it was going to take them on?

Layden: Obviously, we were going to build – or rather, we built – an optical drive peripheral for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Nintendo realised cartridges had already maxed out their memory footprints and so we – or rather, Ken Kutaragi – created the compact disc technology to support the SNES. And we were just about ready. I think it was at CES [Computer Entertainment Show] 1993, we were going to announce the partnership. And Nintendo left us standing at the altar, after they did a pivot at the last minute and went with Philips.

So there was Ken, proverbially standing at the altar with his optical disc drive in his hands. And, indignant, he went back to the leadership at Sony at the time and said: ‘All I need is an OS and some more connecting tissue for this thing, and we can build our own game machine’.

We moved out of Sony’s headquarters to a place in Aoyama, which is about 20 miles away but more in the entertainment district of Tokyo, because they felt that was important to the DNA of the company – and that was probably the best decision the company made.

How so?

Layden: When they decided they were getting into the game business, they knew they had the technology, the engineers. But they said ‘let’s be honest, we sell electronics’. Sony knew that without entertainment DNA, we would not be successful.

They’d look at the Nikkei paper for 45 minutes, drink a cup of tea, and then go: ‘alright, lunch’.

So the initial stage was made a joint venture between Sony Electronics and Sony Music. Half the company was from the music side and, well, you could see it on the shop floor at 8am. All the hardware engineers were at their desks wearing their Sony vests, working on their engineering thing. And then around 10 through 11am, all the Sony Music guys would come in – hungover, sunglasses, cigarettes hanging out their mouths. They’d look at the Nikkei paper for 45 minutes, drink a cup of tea, and then go: ‘alright, lunch’. They’d all stand up. They’d all leave.

We wouldn’t see them again for the rest of the day, because Sony Music populated sales, marketing, advertising, publisher relations. So those were the guys who would go out with the people at Square and ply them with whiskey until the wee hours of the morning to finally get Final Fantasy 7 off of Nintendo and onto PlayStation. When that announcement was made, that was really the ‘oh my god’ moment. ‘Sony’s really serious about this now.’ And that’s down to the music guys, the doggedness of just trying to get a deal over the line. They were amazing.

What other big decisions were made early on, that helped get PlayStation a foothold?

Layden: We had the optical technology, and games were all on flash ROM at that time, so that was a huge leap. ROM carts were $8 to $10 a pop to get blanks, and then you had to get them flashed, usually in Taiwan or in Hong Kong, which meant lead times of six, eight weeks to get stock refilled. Optical discs were $1 a throw and you didn’t have a minimum amount, you could just pop 10,000 out and throw them in the marketplace. ‘If it catches fire, call me on Thursday. I can refill you by Tuesday.’ The momentum really changed the business model of that.

We always knew PlayStation would only be successful if we made it, quote, ‘The People’s Platform’

Sony deliberately never had more than maybe 22 percent of [first-party] software share. On the Sega platforms and Nintendo, first-party had 80, 85, 90 percent of the software market. But we always knew PlayStation would only be successful if we made it, quote, ‘The People’s Platform’. It’s for third parties to come make a business. We’ll come in and we’ll get, you know, 25 percent typically at launch, the share is higher because we put all the bets on the new games. But over time, you know, the real leaders in that marketplace as far as revenue and share goes were the Activisions and the Take-Twos and EA.

Our first party responsibility was to grow the pie overall, and as the pie gets bigger everyone’s slice gets bigger, so everyone’s happy. Growing the market overall meant creating new types of games, new genres of games, and not competing in some of the standard genre categories. And so you got games like PaRappa the Rapper. You got games like SingStar, Ico and Shadow of the Colossus. Who’s going to make those games? It was a first-party imperative to show, firstly, the power of the platform, and then secondly, the endless categories that we could build games into. We weren’t just trapped into three genres and trying to fight for market share from each other.

So I think those are the important decisions taken early on. I think the founders of PlayStation had a really, really keen view on what it took to be successful and how to differentiate it in the marketplace. And a lot of those decisions were taken super early.

Aside from the hardware and games, PlayStation had some memorable marketing too.

Layden: Absolutely. If you look at the Japanese TV advertising, it was like nothing you’d ever seen in gaming. Gaming advertising had been really straightforward. ‘Here’s the character, here’s the action scene.’ But the advertising team at PlayStation came from Sony Music, so we were marketing games like you market rock bands – with a little of the mystery, a little of the sexy. It was the same in England too.

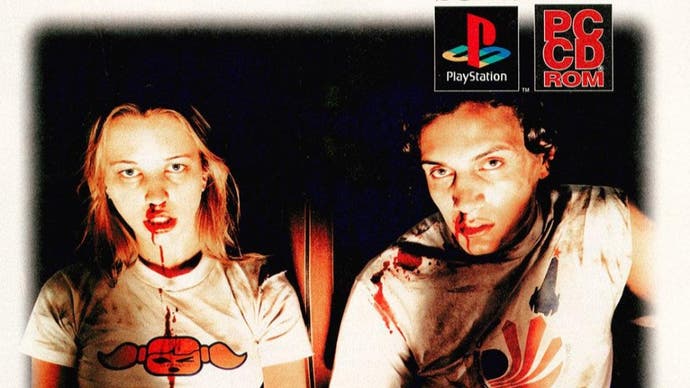

Yes. WipEout here had a memorable advert that caused some controversy, back in the day. And then there was the suggestion the ‘E’ in the game’s name was a nod to drugs culture.

Layden: [Laughs] I think these urban legends are cool, and people extract meaning where there wasn’t necessarily one. I think the innovations of WipEout were us teaming up with creatives like Designers Republic, who were at the top of their game. The Wipeout packaging was like nothing anyone had ever seen before, except maybe on like an EDM album cover. And then the music – I thought that was genius too. I was in Japan when WipEout released, so I had to bring it to Japan and localise it for the Japanese market. But it helped that Japan hadn’t heard of the Chemical Brothers or Crystal Method or Prodigy. WipEout was like a music introduction vehicle.

You’ve got your vodka Red Bull in one hand, and you’re playing WipEout with the other.

And in London, I would come over on business to go to Sony Liverpool and see the guys up there, and we’d be going to clubs during that time and see PlayStation 1 kiosks with WipEout in nightclubs. You’ve got your vodka Red Bull in one hand, and you’re playing WipEout with the other. It was the beginnings of making gaming into a lifestyle, the beginnings of making it something where gaming is more than just a distraction. All of a sudden, gaming became less something whispered about in pubs and more you overhearing someone saying ‘oh I’m playing Tomb Raider’. ‘Oh, Tomb Raider. Oh, do you play games? That’s cool.’

I think for a lot of folks, coming home from the pub or the uni bar and playing WipEout was a bit of a ritual. Even if playing it at that point was difficult.

Layden: Let’s be honest, the original WipEout is rock hard. It’s unforgiving. And honestly, you know, we’d do that too, come home from the pub and play. You can’t play it, but you laugh your ass off. Everyone can’t take the first corner. With the sequel, we did make the handling a bit more forgiving.

Specifically for people back from the pub?

Layden: Not specifically but it was definitely a benefit to them. And for people like me, who could barely get into the original WipEout without throwing my controls at the screen.

What was it like being part of those early conversations around what consoles could do? You were on board when Sony came up with the Cell Processor, the Emotion Engine – these magical terms that now seem to have gone away. What’s changed?

Things like the Emotion Engine and the Cell processor were the biggest headaches of the day

Layden: From a development perspective, things like the Emotion Engine at the heart of PlayStation 2, and the Cell processor at the heart of PS3, were the biggest headaches of the day. Trying to learn to build for those proprietary architectures required you learn new skills to get the most out of them. Naughty Dog always found a way to get under the hood of the tech before anybody else. Of course they had early access, but they burrowed deep. Being platform exclusive allowed you to push the limits of that platform’s capabilities and you didn’t have to make compromises, which you do when you do a multi-platform product. It’s like, ‘don’t push too hard on the frame-rate, because this other platform can’t handle that’.

Rather than make two versions of the same game where one looks remarkably better than the other, you just sort of balance everything out so it all looks the same. It’s why the PlayStation homegrown stuff looks better on PlayStation than anything else, because that’s all they do. That’s all the tech they need to know about. And I think that gave special advantages on PS2 and PS3, which took other people a long time to catch up, but that wasn’t necessarily a good thing. It was a bit of a headache, and there was a huge cost involved. PS3 hardware took a long time to get to profitability, a long time, whereas when we launched PS4, it was pretty much a non-loss product from day one.

I remember being at Sony’s Tokyo headquarters for the PS4 launch, and the console’s near-immediate profitability clearly being a big deal.

Yeah, and that comes down to us moving to more commoditised silicon. You know, I think there was a vision at one time where the PS3’s Cell processor would somehow go off-platform and compete in the world of CPUs with the likes of Intel and Nvidia and AMD and others. But that didn’t happen. And without that happening, all of the economies of scale that you might have predicted for the technology were impacted negatively, because you couldn’t build enough of them [fast enough].

What was it like at Sony during the PS3 era? Of all the generations, I think it’s the one that stands out as having been the biggest struggle to get right.

We flew too close to the sun, and we were lucky and happy to have survived

Layden: PS3 was Sony’s Icarus moment. We had PS1, PS2… and now we’re building a supercomputer! And we’re going to put Linux on it! And we’re going to do all these sorts of things! We flew too close to the sun, and we were lucky and happy to have survived the experience, but it taught us a lot. And going to PS4, we learned things like: buy it, don’t build it, if you can. You can manage the cost better. You can argue with vendors, get better deals instead of building your own thing.

We also learned that the center of the machine has to be gaming. It’s not about whether I can stream movies or play music. Can I order a pizza while I’m watching TV and play? No, just make it a game machine. Just make it the best game machine of all time. I think that’s what really made the difference. When PS4 came out, it set us against what Xbox was trying to do. [They wanted to] build more of a multimedia experience, and we just wanted to build a kick ass game machine.

Which lead to Shuhei Yoshida’s legendary ‘here’s how you share games on PS4’ video…

Layden: That was created on the fly, in the moment, when announcements were made by other people and we said, ‘what’s our answer to the sharing question?’ And in a moment of inspiration, they came up with that. And it was… it was devastating in its simplicity.

That’s what you need sometimes when you’re riding too high on your own supply

PS3 got us back to first principles, and that’s what you need sometimes when you’re riding too high on your own supply. You take a little tumble, you hit your head on the wall, and you realise, ‘I can’t continue to operate this way’. PS3 was a clarion call to everybody to get back to our first principle.

Over time, we had the PS3 fat, then the PS3 not-so-fat, then the really tiny one. And that was all just in the pursuit of ‘it’s a game machine, make sure it’s a game machine’. That’s all we did here. And, by that time, the learning curve on the Cell processor was solved so a lot of developers were able to come out with stuff. The first couple of years, though, that was pretty grim.

We learned a lot and we were able to put it into practice. Learning is one thing but then, based on that learning, the question is – can you execute a different approach? Sony had the ability and the capability to take a deep look inside and go, ‘we’ve got to stop doing these things over there’. We had to start doing these things like we used to.

Stepping back to PS1 then for a moment, as it is its anniversary – what are your favourite games from that era?

Layden: The first game I worked on – a localised Japanese version of a game called ESPN Street Games. It was just a number of mini-games, just going down the streets of San Francisco on a skateboard, on a luge, on a mountain bike, and just racing. It was super simplistic, and the graphics, looking at it now you go, ‘Oh my God. How pixelated is that?’ But it was exciting, and it gave me a good understanding of the excitement around couch co-op or couch competitive play. That will always be my first love, because that’s the first game I worked on.

That was the first time we had to create a sticker that says ‘explicit content’ – you know, ‘mothers beware’

Later on, I love the stuff we did with things like PaRappa. Sadly, I think PaRappa is a game that probably doesn’t get made today because so many publishers are risk averse on doing new things. Vib-Ribbon, from the same studio, I loved. Also Biohazard, or rather, Resident Evil. When that came out, that was a shocker. That was the first time we had to create a sticker that says ‘explicit content’ – you know, ‘mothers beware’ – on the box. But more than that – Resident Evil created an entire new genre, as the idea of survival horror didn’t exist beforehand. When that came out from a third-party, not from a first-party, we were validated with our idea that game companies could do something new here. We weren’t just going to be about JRPGs, or another fighting game or some racing game. We worked very closely with Capcom to get the right promotion around Resident Evil in Japan.

And then Metal Gear came out with stealth action – what is that? Kojima made it happen, and that created another new genre. It’s about growing those pies. It’s making more categories, getting more people into gaming. I think that is something PlayStation spent a lot of a lot of time thinking about and trying to do. Not just simply to grow the market, but also to give it longevity and stability as a medium.

Were you ever jealous of a game on a rival platform?

Layden: The one time I really felt jealous… I’m going back to my time in Tokyo on PS1. My job was to bring Western titles to Japan. And in your local parlance, that’s like bringing coals to Newcastle, right? I would bring things like Twisted Metal to Japan, and the Japanese market would go ‘what the hell is that?’. But one game I saw early on, and I heard the buzz, and I went out to Core Design in Darby because… I wanted to get Tomb Raider for the Japanese market. I wanted it to be on PlayStation. And I saw the Smith brothers, and we talked about it, and they were really excited about the concept. We talked it through. They talked it through. Bada bing, bada boom… they signed to bring it out on Sega Saturn. Sega?! And then shortly thereafter, they did get it onto the PlayStation in Japan as well, but it launched on Sega. And yeah, that always felt… What could I have done to have actually gotten it? But I came that close.

Finally, is there one classic franchise or game that you’d like PlayStation to go back to?

Layden: This is just a personal preference. This is just a game that spoke to me when I first saw it, and I love the guys working on it – so much so we got a sequel out of it, which was also fun and fabulous and I was able to get it remastered for PS4… I would love another whack at MediEvil. The Cambridge studio guys were called Millennium at the time they were making the original MediEvil and Sony bought them shortly thereafter. The humour is kind of Tim Burton meets Monty Python though it was really hard to localise the comedy into foreign languages. If I could wave a magic wand and have one more bite at an apple, it would be the MediEvil apple.

Join us tomorrow for the second half of our exclusive interview with Shawn Layden – this time looking forwards at PlayStation’s future – and how the future of console gaming will change over the next three decades.

fbq('init', '560747571485047');

fbq('track', 'PageView'); window.facebookPixelsDone = true;

window.dispatchEvent(new Event('BrockmanFacebookPixelsEnabled')); }

window.addEventListener('BrockmanTargetingCookiesAllowed', appendFacebookPixels);

Leave a Reply