Half-Life 2 turns 20 today. I came to the series late, only playing through the first two games and their expansions in preparation for Half-Life: Alyx, so unlike many fans, I haven’t spent most of the last two decades waiting for Valve to count to three.

What a gift that turned out to be. When you haven’t played (or watched, or read, or listened to) a classic, there are few feelings as good as finally checking it out and finding out that, yes, it really is as good as everyone has been saying all along. Half-Life 2 is one of those truly classic classics.

Related

My First Time With Half-Life 2: Painting Ravenholm Red And White

A spooky gravity gun tech demo is where I found my love for Half-Life 2.

Half-Life Has Always Been About The Journey

With Half-Life 2, Valve captured the feeling of being on a journey. Gordon Freeman has always been in motion — until Half-Life: Alyx, all of these games and expansions, save Half-Life 2: Episode 1, began with their protagonist in a vehicle. The tram to Black Mesa delivers Gordon in the original game and Barney in its expansion, Blue Shift. Shephard, the Marine who stars in Opposing Force, arrives via helicopter.

That motif continues in the sequel, when Gordon enters City 17 by train. Episode 1 may buck the trend, but it ends with Gordon and Alyx escaping City 17 on a train, and Episode 2 picks up after that train has gone off the rails, as Gordon moves through the train cars, looking for a way out. Half-Life introduced itself to audiences as a journey, and has never stopped trekking.

That continues throughout Half-Life 2, and it’s the vehicular section in the middle of the game, Highway 17, that is the heart of the game. In Highway 17, Gordon takes a modified four-wheeler on a lengthy voyage up the Coast. Though he stops periodically to solve a puzzle or help resistance fighters, for much of the journey, Gordon is alone. His only real company are the antlions that emerge from the sand to leap after his buggy. If Alyx or Eli were along for the ride, it would be a road trip. Instead, this hour of the game feels intensely isolating, as you find beauty in the barren dunes and icy gray sky.

Separation Anxiety Is Good For Games

Stories can show the importance of a relationship between two characters by separating them. God of War Ragnarok got a lot of mileage out of this, sending Kratos and Atreus on separate quests for much of its intertwined campaigns. But my favorite example is the hotel level in The Last of Us. Joel falls down an elevator shaft, leaving Ellie alone several stories above as he navigates the dark, flooded basement alone. It’s the first time he has been separated from Ellie since meeting her, and that means it’s the first time we have been separated from her, too. That distance brings home how much you’ve come to care about her. The first time I played it, I found myself worrying about her, hoping she was okay.

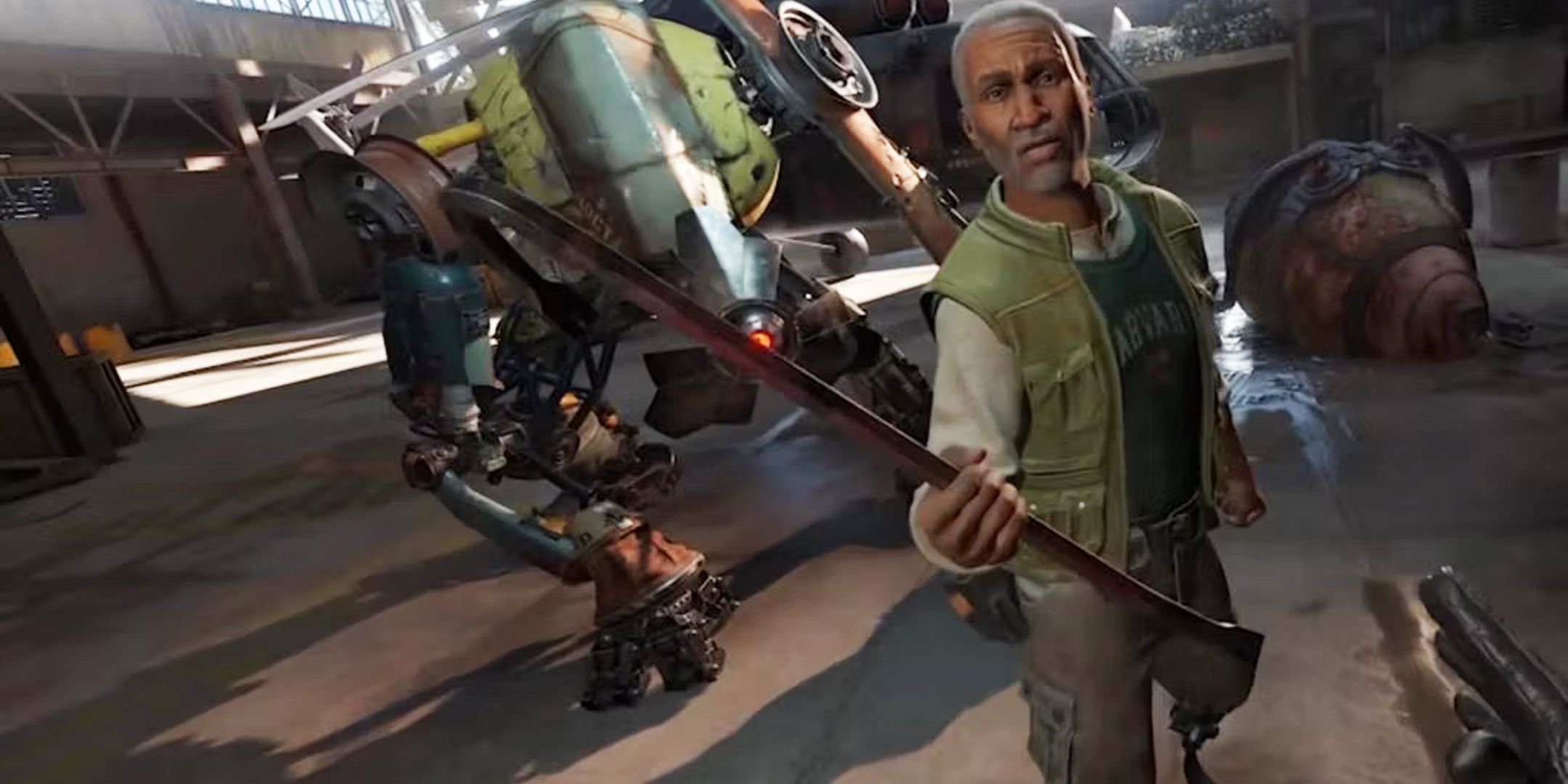

Half-Life 2 has a similar approach to the relationship between Gordon and Alyx. We meet Alyx for the first time in the first chapter, Point Insertion, when she rescues Gordon and leads him to the resistance. But when a teleportation to Black Mesa East goes awry, they’re separated, and Gordon spends the next few chapters traveling to the hideout alone.

After a brief reunion, Gordon is forced to go off alone again, traveling through Ravenholm in one of the game’s best levels. At the end of Ravenholm, Gordon arrives at Shorepoint Base. It’s a resistance HQ, but Alyx isn’t there, and Gordon sets out to rescue Eli Vancefrom a Combine prison. This is how Highway 17′ begins: with the hope that, maybe, eventually, you’ll find your friends again.

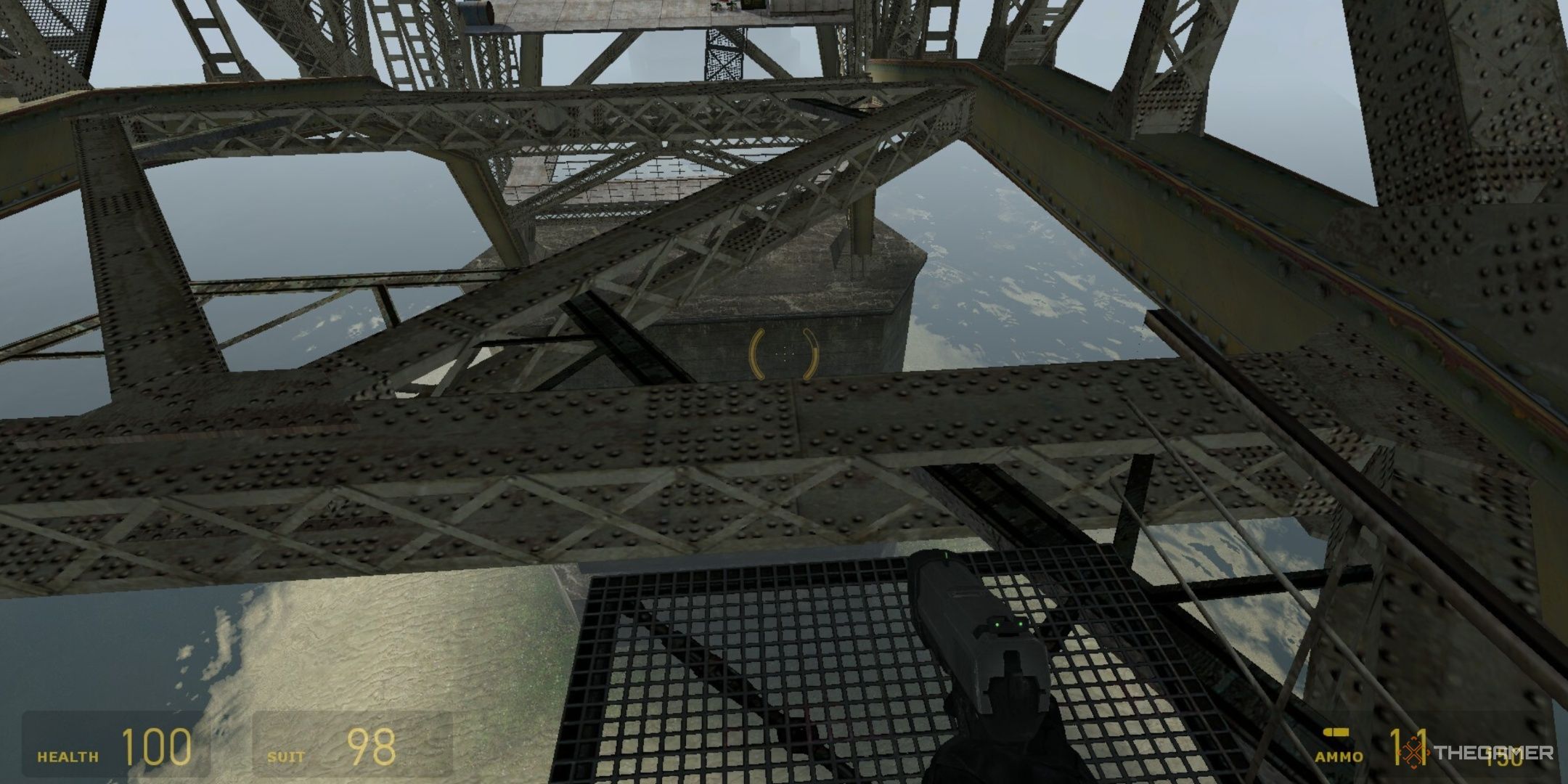

The Lonely, Windy Bridge

Highway 17 isn’t a very long section, and only takes about an hour to complete. It isn’t that isolated, either, as Valve has Gordon run into resistance fighters who need his help along the way. But it feels lonely. You’re wondering when you’ll get to see Alyx and Eli again. You travel one lone road through seemingly endless countryside. There are no other cars, so no other engines making noise. The sky is a gloomy slate gray. And the houses along the way are empty, save headcrab zombies and Combine soldiers. When lone gull cries break the silence, it feels like you can hear it echo for miles.

This intensifies when you reach an energy wall you need to shut down at the level’s climax. The switch is at the end of an ominous metal bridge that sways in the wind above the glassy water below. As you make your way along the beams, you can hear the wind blowing, the steel creaking. You are surrounded on all sides by gray, the ocean below and the sky above. Eventually, you reach the end and get into a firefight with Combine soldiers and a dropship. But, as you make your way there, you are incredibly aware that Gordon is profoundly alone.

No other game has ever captured that feeling so well. Though ‘Ravenholm’ is the game’s best-remembered level, it’s the quiet, reflective journey that begins in its wake that defines Half-Life 2 for me.

Next

What Would Half-Life 3 Even Look Like Now?

We break down the cancelled Half-Life games and how Alyx’s ending might change where Half-Life 3’s story goes.

Leave a Reply