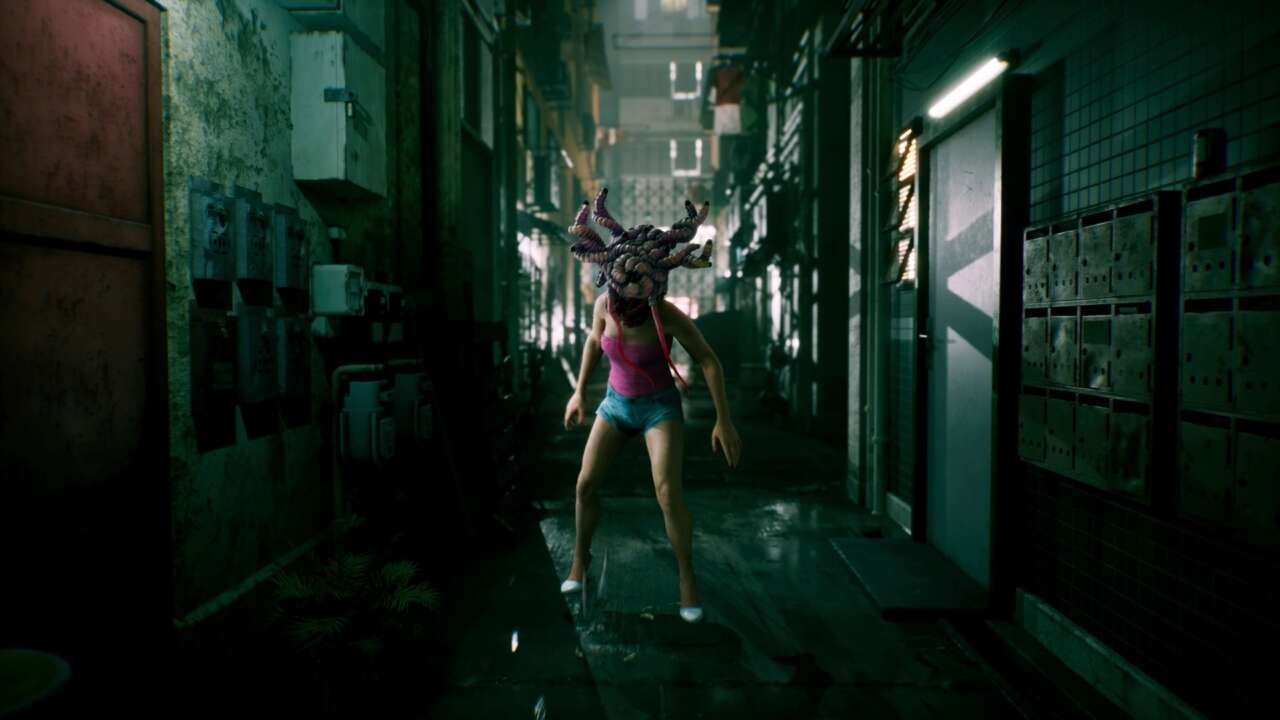

Third-person action game Slitterhead often presents a pretty compelling front. At first, it sounds like an out-there horror game with an inventive approach to gameplay. You play as a formless spirit that can possess humans, hunting vicious monsters capable of imitating normal people. Those creatures explode from the heads of their human bodies to reveal their true forms when discovered.

As cool as all those words clearly are, Slitterhead never reaches the promise of its premise, apart from a few gorgeous cutscenes where a human twists and mutates into a disgusting, multi-armed abomination. Instead, it’s usually frustrating and repetitive, with its interesting ideas turning to gimmicks that wear themselves thin after the first few hours.

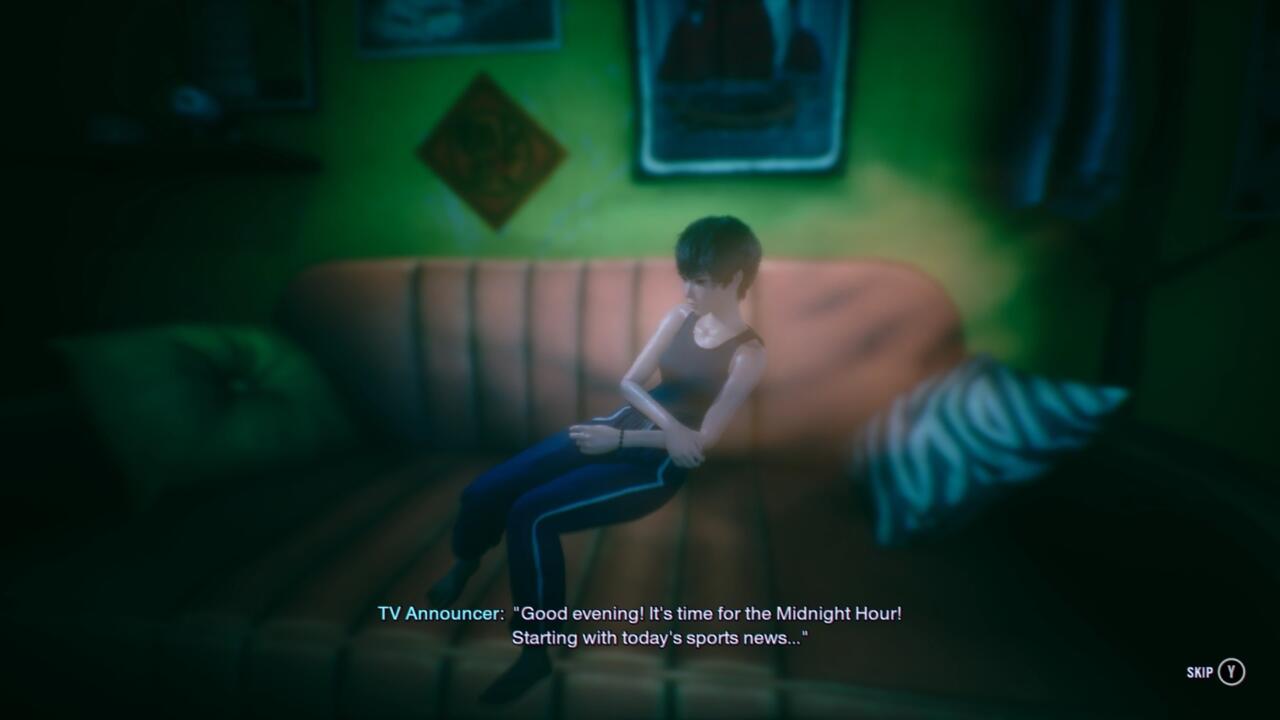

Those gimmicks feel like they have potential, at least at first. Slitterhead opens with you taking on the role of the Hyoki: a floating spirit that can zip into the brains of random humans populating the dense city of Kowlong, briefly taking control of their bodies. The Hyoki can’t remember anything about itself or what it’s doing, until it encounters its first slitterhead–which, after eating the brains of an unsuspecting victim, bursts from the skull of its host and chases you down alleys as you zap from one hapless soul to another to stay just ahead of it. The concept is weird, changing the way you think about characterization and physical gameplay space, and slitterheads are scary–it’s a great way to start the game.

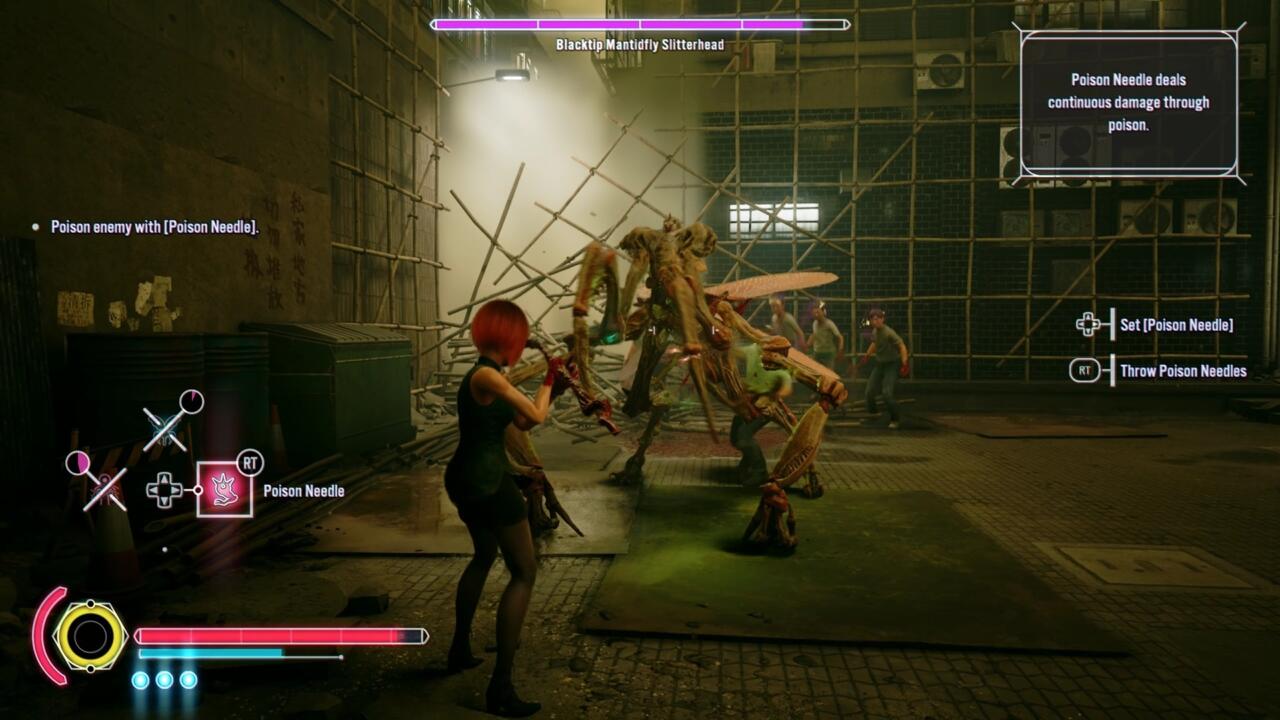

But this is the only time you’re on the back foot or that Slitterhead makes use of the horror aspects of its premise. For the duration, you’re hunting the parasites with the motive of exterminating them, and it’s the monsters that run from you. As you leap into humans, you can use their blood to briefly create solid weapons like clubs and spears, allowing you to go toe-to-toe with the giant octopuses and praying mantises that erupt out of the necks of their unfortunate hosts. Humans are physically weaker than slitterheads, but each new body you take over gives you a new health bar to run down, as well as the element of surprise to go after a creature while it’s slashing up the poor meatbag you just abandoned. As a combat system, the idea of making use of a crowd to constantly confuse and overpower your enemy with an endless series of ambushes is a fun one.

Gallery

Slitterhead adds to the idea when you start finding Rarities–humans who form closer bonds with the Hyoki to make their possession a little more of a partnership, and who sport special abilities as a result. Those abilities tend to reflect each of their personalities and vocations. You might heal nearby allies or summon more humans to a battle, power up your melee weapons to set enemies on fire, throw exploding weapons, or even turn humans you possess into kamikaze time bombs. And all humans can dodge away from attacks and block or parry some blows, which can give you opportunities for big counterattacks–deflect enough strikes and you’ll trigger a brief period of slowed time in which you can wail on an opponent with everything you’ve got.

The components of Slitterhead’s combat ought to come together to make for something unexpected and entertaining, but fights are rarely all that engaging in practice. While there are a few different kinds of Slitterheads and they sometimes bring different attacks to bear against you, for the most part, they all fight the same way. Even still, I never quite felt like I could get the hang of the parry system thanks to the speed and angles at which attacks come at you. The system lacks the feeling of being tight and reliable, and I was frequently oscillating between being able to perfectly parry one slitterhead to make a fight completely trivial, only for the next one to body me over and over.

Standing your ground is a worse way to fight, though, when you can just consistently zap into another body and hit a slitterhead in their vestigial, dangling human body, where they’re most vulnerable. Each time you jump into a new host, you gain a boost to your melee damage, as well as what more or less amounts to three or four free hits since the enemy AI will attack the body you were previously in for a while before it realizes you’ve moved into a new one. Even that is more frustrating than fun, though. The combat system is loose and clumsy, causing you to swing past an enemy as often as into them, even when you use the lock-on system. And that’s if the lock manages to survive between bodies. Often, it’ll disengage, requiring you to swing the camera around madly as you reorient yourself just to get a couple of quick, boring hits in, before you repeat the process.

And while bringing different Rarities into a mission might suggest a strategic plan of mixing specific abilities together, in practice, there’s just not a lot going on there. All the Rarities are pretty effective, but many of their special moves don’t bring enough to a battle to change its flow. Throwing bombs, zapping enemies with poison, setting traps around the battlefield–none of them change the fact that combat mostly entails just hammering the melee button before swapping to a new body and hammering it again. Many special moves require blood, which you also use for health. If a body takes critical damage with you in it on three separate occasions, you die, and you can’t be outside of a body for more than a few seconds or it’s game over, so using these abilities can make you very vulnerable. With slitterheads often hitting like a truck to send your hosts flying and the parry timings and directions rarely feeling like you can rely on them, you get a situation where most special abilities just aren’t worth the risk.

Some abilities do have their uses–summoning more humans, for instance, is usually a worthy tradeoff, and an attack with a magical chaingun lets you basically swap your Rarity’s health for damage against an enemy, and it’s not too difficult to recharge if you can slip away from a foe for a couple seconds. But most of the abilities are a lot less strategic. I never found myself happy when I summoned the weak stationary turret that shot intermittently at enemies, and the ability to charge up your weapon into an explosive bolt always took too long to execute in any actual combat situations.

You’re not always fighting slitterheads, though. Sometimes you have to use stealth to make your way through an area, which has the potential to be a fresh take on familiar tropes but winds up being far too simplistic. You can briefly pop out of bodies and float invisibly around an area, allowing you to peek around corners to avoid threats, and sometimes you can’t get a body past a guard without being detected, forcing you to abandon one host for another further along. But guards walk short, obvious prescribed paths and never do anything unexpected. The stealth portions become extremely tedious and slow digressions where you make your way along an obvious path, and if it’s ever not obvious, the Hyoki explains exactly what you should do and how.

And sometimes you’re searching for slitterheads, using your special powers that direct you to their locations and even let you temporarily “sight jack” them to see what they’re seeing. These scenes represent another exciting idea that would be great if they required any brain power at all, like if you had to use your knowledge of Kowlong’s locales and landmarks to figure out where a slitterhead was heading or what it was planning, but you never do. Instead, you just follow a glowing trail to the enemy and attack them. Other times, you’ll get into a chase scene with a slitterhead as it flees through the streets, and not only are these always exactly the same, but also always annoying. They mostly amount to zapping from human to human to take a random swing in the direction of the running slitterhead as it passes until you finally whittle down its health enough to trigger the real fight, or you reach the end of whatever prescribed path it was running, and trigger in the real fight. Regardless, chases aren’t fun; they require no particular skill, they offer no challenge, and they carry no stakes.

The narrative is where the game could make up ground through its imaginative premise, but here too, Slitterhead looks deeper than it ever actually is. At first, you’re just killing whatever monsters you come across, but you soon start to realize that hidden slitterheads are doing more than just snacking on the brains of whoever they can coax into a dark alley. They’ve taken over organized crime in Kowlong’s slums, using sex workers as a means of luring in victims.

That early element of the mystery–the revelation that the head-popping, brain-slurping monster mimics had decided to do regular crime stuff while also occasionally eating their customers–was pretty disappointing. As inventive as it might be to have these fiends roaming the city, their goals and motivations can’t match their often-inventive creature designs. And while the game suggests that it means to flesh out the slitterheads themselves as the narrative unfolds, that element of the story ultimately doesn’t really go anywhere. It’s never clear exactly how the slitterheads work, what they think or feel, or what they’re all up to. They’re evil and you need to kill them; anything else is wheel-spinning.

Some aspects of the story do get better as the tale goes on, at least to some degree. In between missions, you can talk with each of the Rarities you unlock, learning about them and deepening their connection with the Hyoki. When Slitterhead leans into this idea, it goes to some cool places. For instance, Julee–your first Rarity–isn’t happy with the collateral damage that often results from the slitterhead hunts, encouraging you instead to limit civilian casualties when possible, and that has a notable effect on the Hyoki, who started the game by leaping off a roof in a human body and then zapping out into a new one at the last second because it was quicker than taking the stairs. Alex–another early Rarity who contrasts Julee–is bent on personal revenge against the slitterheads, and he has little regard for anyone who gets in his way, even if they’re completely ignorant to what’s going on. Both characters influence the Hyoki as time goes on, and the story starts to take on some dimension as their different viewpoints and ideologies expand and clash.

Unfortunately, the other Rarities aren’t nearly as compelling. There are eight altogether, but only one other than Julee and Alex has any narrative to speak of, and all are two-dimensional stereotypes. They include a sex worker with abilities related to her feminine wiles, a homeless man who wishes to spend most of his time drinking, a high-school nerd, an old woman who seems to have dementia, and a housekeeper who relates everything she says to cleaning. Overall, they have little to contribute. They’re never written with anything other than surface-level characterization and weak jokes that play off their stereotypes, and apart from a couple of missions where you bring along a specific Rarity to open a door or provide a little information, they’re incidental to the plot and their conversations are often sort of pointless.

And while some aspects of the story develop in interesting directions, Slitterhead never succeeds in translating that intrigue into gameplay. Instead, like the combat systems, level design is repetitious and shallow. Time travel becomes a major element of the story after the opening hours, which brings its own intriguing ideas to the narrative, but the practical result is that you replay the same missions, in the same locations, over and over. Sometimes you need to go back and seek out additional Rarities or hunt for collectibles. Sometimes you’ll play through a mission to a different outcome, or open a door you saw in a previous run to access a new small area, but ultimately it feels like Slitterhead is made up of the same four or five levels, with the same boring fights and frustrating chases, over and over.

It feels like piling on at this point, but it also must be mentioned that Slitterhead is, largely, a pretty ugly game. Character faces are plastic, glossy, and largely unmoving, and while the slitterheads themselves are often cool-looking, since you fight a few variations on the theme over and over, they stop being visually compelling in a hurry. There’s a lot of style in the game–opening title cards carry cool graphical effects, missions end with a neat freeze-frame “To Be Continued” message, and there are times when the presentation is artfully cinematic or knowingly horrific, hinting at what the whole experience could have been like. Gameplay, though, looks 15 years out of date, and it’s bad enough to be distracting, especially when the game puts heavy emphasis on talking to characters to advance the story.

Really, though, most things about Slitterhead feel out of date in this way. The body-swapping combat, RPG-like team of possessable people, the monster-hunting semi-paranormal narrative–they’re all exciting until you engage with them a little, when they reveal themselves to be shallow and underdeveloped. The actual experience of playing Slitterhead is constant repetition of systems that aren’t very engaging even their first time, across levels you’ll see over and over again, telling a story that never makes much sense, with characters that feel like first-draft lists of stereotypes. Slitterhead has a lot of fascinating ideas and compelling gameplay on the surface, but beneath, it’s just boring and banal–a bunch of scary-looking monsters who turn out not to be very scary at all.

Leave a Reply