A relatively minor instalment, but in a series this magical, that’s still good news.

The telescope is not quite a telescope, but it still works like one. And, more importantly, it still feels like one. You put your eye to the glass and then you move left and right to scan a glorious horizon drawn in sunny skies and churning ocean currents. What’s out there? What’s waiting for me? Where next?

Mario & Luigi Brothership review

- Publisher: Nintendo

- Developer: Nintendo

- Platform: Played on Nintendo Switch

- Availability: Out on 7th November on Nintendo Switch

This is my favourite moment, my favourite little ritual, in Mario & Luigi: Brothership. Brothership’s the latest in a much loved series of RPGs in which the brother in red and the brother in green head off on an adventure together, completing quests and side-quests, engaging in exploration and puzzling, and getting stuck into turn-based battles. Brothership’s best new idea lies with the telescope, and it’s also hinted at in the game’s name. This time, you float around on a hub that’s also a ship – it’s also an island, incidentally, and it’s called Shipshape, which isn’t a bad pun – and you’re regularly tasked with tracking down the scattered islands that make up the world of Concordia, before climbing each island’s lighthouse and using it to connect the island to your home vessel. Gather those islands. Reunite the world. Onwards!

Thematically, this is all a little muddled, I know. Islands, but you connect them all via lighthouses? And almost everyone I meet is a kind of anthropomorphic plug socket or computer port? At times – any time you think too much about it – Brothership’s narrative can feel like the joke adventure that Paper Mario once sent Luigi on to explain his absence from the game. Mario would be off on a quest that made some kind of sense, but every now and then Luigi would check in with some true RPG weirdness. You know, like collecting islands, or hanging out with talking plug sockets.

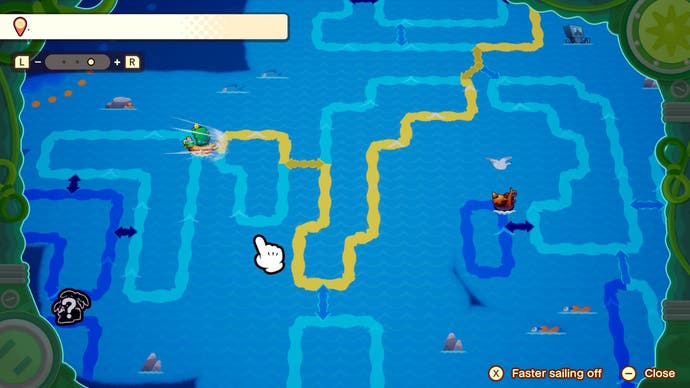

None of this matters, because the ship and the ocean means that every hour or so, Brothership gets to send you somewhere new. You spot an island on the sea, you play a little game to connect your currents and head for it, you spend any travelling time levelling up or side-questing on previously explored islands that often change a little overtime, and then, when you get close: into the telescope – the telescope that is also a canon – and off through the sky to a fresh beach, a fresh world.

Sometimes, but not always, Brothership uses these islands to genuinely reinvent the game. There will be characters to meet and self-contained stories to coax to their conclusions, with puzzles that fit in thematically and set-pieces that feel truly joyous and shift the genre a little. These things happen most frequently in the back half of the game, I want to say, and I don’t think they should be spoiled. Some of the time, though, the island’s largely just a new biome – a desert, jungle, a garden – and a home for more puzzles and trinkets and combat. No matter. This stuff is still great.

The first Mario & Luigi game was more than great, of course. Superstar Saga, back in the days of the GBA, was a proper classic, and it was a classic largely because it made so much fun from the idea that you were controlling two characters rather than one. I remember precision arpeggiated jumping just to get the brothers up staircases, and sequences in which I had to control both of them as we faced off against the ultimate foe: a skipping rope. What days! By the time of Brothership, it’s all cooled off a little. Out in the world, you can make Luigi jump if you want, but a lot of the time he takes care of himself as he follows Mario around. But you can use a trigger to get him to interact with highlighted objects, and then – then there’s Luigi Logic.

Luigi Logic is the game at its most lovable, I think. Every now and then, exploring the world or facing the boss, you’ll reach a kind of impasse. Luckily, Luigi will often have a brainwave, leading to a little set-piece puzzle out in the world, or a mini-game that does massive damage to a boss. These moments are often pretty straightforward, but they’re presented beautifully. A close-up of Luigi pondering, frowning in concentration, and then it all dawns on him. The instance of the fingerpost! Luigi Logic.

These moments often lead to sequences that feel like the classic Mario & Luigi games. Luigi will man a switch while Mario moves off on platforms that Luigi is then controlling, or through a maze with pipes and junctions that Luigi can turn. The game uses picture-in-picture on occasion, which is always a weird video game gimmick that I am thoroughly here for, and it’s just a reminder that at the centre of these fairly traditional RPGs is a special ingredient: two players, a knife and a fork.

I’ve really enjoyed Brothership, but I have caveats. For one thing, and this is maybe just my patience fraying slightly as I get older and meaner, I find the stop-startiness of it increasingly awkward. I’ll be setting off to do something and then there will be a cut-scene to dismiss or a dialogue section that I can speed up but not skip. It’s not just that it tangles the flow, it’s that it doesn’t really feel like Mario, which is commonly so rare to interrupt players. That said, I don’t know if it’s the shift in developer to a team that’s less succinct, or if it’s actually any worse here than it has been before, so maybe chalk this one up to my gathering decrepitude.

The other big thing is that the combat system, while fun, is exposed over the course of a long game. It’s still good straight-forward fun, with Mario and Luigi teaming up to bonk enemies in a manner that requires interlacing button presses as each brother does their bit – you know, Mario jumps, Luigi catches him and lobs him back for another go, and then you reverse inputs when it’s Luigi’s turn. There are some ingenious enemy designs and bosses, and some of the special attacks have a nice back-and-forth complexity to them as you knock a shell to and fro, say.

Mario & Luigi: Brotheship accessibility options

Failing a battle steadily reveals easier settings, but you can’t just select easier settings for every battle – you need to fail each battle multiple times.

There’s a new plug system in combat, too, which sees you unlocking special moves and modifiers that you can swap in and out, searching for synergies and managing cooldowns. But when you’re largely opting to stomp or hammer or pull off a gimmick attack, it can become just a little bit of a chore over time. I never minded battling, but I noticed several times that its puzzle sections – which had relatively few enemies to deal with – held my attention much more. Not just that, it felt like the game was following the grain of its own materials at this point. Brothership offers some lovely sequences, but the mainly-decent combat can feel like a little too regular of an intrusion.

Yes, yes. All of this stuff is a little annoying. But while Brothership isn’t the series at its very best, it’s still a Mario & Luigi RPG, and these always contain moments of colour and wit and invention that I’m extremely glad I was present for. Mario and Luigi are already money in the bank, in other words. Throw in a bit of island hopping and I’m still happy.

A copy of Mario & Luigi: Brothership was provided for review by Nintendo.

fbq('init', '560747571485047');

fbq('track', 'PageView'); window.facebookPixelsDone = true;

window.dispatchEvent(new Event('BrockmanFacebookPixelsEnabled')); }

window.addEventListener('BrockmanTargetingCookiesAllowed', appendFacebookPixels);

Leave a Reply